Home » Causes of WW1

Category Archives: Causes of WW1

13 albums of images and grabs relating to the First World War

‘Grabbed’ and curated for a multitude of reasons I compile these albums while researching a topic, to put family photographs in one place, to pull together a theme that interests me and often to remind me of great TV and films on the First World War. Links are easily made from these to blog posts.

|

| WW1 – Bite and Hold |

‘Bite and Hold’ pulls together charts and book covers, and images from the Third Battle of Passchendaele used to put together arguments for the actions taken by the British Army in 1917 as something less than futile.

|

| WW1 – On Film & TV |

‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ was my grandfather’s favourite film of the First World War. I was able to take a portable TV and VHS cassette player to show him the film in his my 90s.

|

| WW1 – Talbot House, Poperinge |

Talbot House is remarkable spot today as it was 100 years ago. As well as the museum and gardens you can stay there a few nights too. There’s a health contemporary link to local schools and colleges with a curious studio full of artworks themed from the war.

|

| WW1 – Why did Great Britain go to war in 1914 |

A question that everyone must have regarding the First World War is what caused its outbreak. The BBC TV series got close, though for academic answers publications of many original documents courtesy of the likes of Annika Mombauer make it clearer still.

|

| WW1 FL Memorials |

For decades I have stopped to read war memorials across the UK and even when working in France. I didn’t always photograph these, but those I have photographed recently I have added here. I have boxes of slides somewhere that need to be digitised. These were pulled together to share in a recent online course on FutureLearn on Trauma and Memory.

|

| WW1 Heroism |

These were pulled together to share in a recent online course on FutureLearn on Trauma and Memory.

|

| WW1 Ypres 2013 |

96 years after my grandfather passed through here I spent a few days between Poperinge, Ypres and Houthulst Forest walking in the paths he took and establishes where the piillboxes where he operated a machine gun could have been.

|

| WW1- Great War Diaries |

Grabs recalling the very best series of war diaries reconstructed I have yet seen during these centenary years.

|

| WW1-First World War |

A bulk collection of everything I have on the First World War, some 800+ images from books, albums and magazines.

|

| WW1-In Flanders Fields – Ypres 2013 |

The wonderful ‘In Flanders Fields’ museum in Ypres is an inspiration.

|

| WW1-IWM BBC WW1 |

Thinking through ideas related to how the First World War is commemorated.

|

| WW1-Jack Wilson MM |

Everything I have from my late grandfather: his photographs, as well as photographs of his medals, logbook and other bits and pieces. Here are every map and image I’ve thus far found that could help to illustrate his story from Shotley Bridge, County Durham to northern France, the Somme, Ypres and then through training with the Royal Air Force in 1918.

|

| WW1-Passchendale DbyD |

Of all the battles this is the one where my grandfather served in key events: Langemark and Passchendaele in particular going in and out of the line on several occasions – surviving where many of his friends died and receiving the Military Medal for keeping the gun in action over a week in Courage Post on the front looking into Houthulst Forest in late October 1917.

Why did Britain go to war in 1914?

The complex reasons that took Britain to war

A handful of belligerent political leaders, primarily in Berlin, but also in Vienna, exploited the murder by a youthful, idealistic Serbian nationalist of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28th June 1914 to realise the long-held belief in German governing circles for ‘Welpolitik’ (word policy), even a right to ‘Weltmachtstellung’ (world power). Leaders in both Russia and France did more to aggravate than to alleviate Germany’s paranoia over encirclement on the one hand, and frustrated rivalry with these established empires for land and influence around the globe.

1. Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary with his wife Sophie and children

Ultimately, and especially after the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the machinations, deviousness, obfuscations and at times ineptitude and delusions of Germany’s leaders led Britain’s elected leaders, reluctantly, in August 1914, once all efforts at mediation had failed, and enough of Britain’s divided Conservative-Liberal coalition cabinet had united after Germany’s invasion of Belgium, to go to war when Germany failed to respond to Britain’s 4 August 1914 ultimatum.

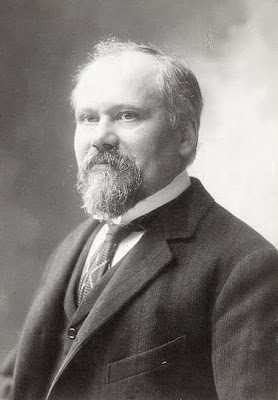

2. Theobolad von Bethman-Hollweg, Germany’s Riechs Chancellor

Original documents identified and collated for the purposes of explaining the actions, decisions and feelings of the participants in the lead up to what became a world war (1914-18) by the likes of Imanuel Geiss (1967), John Röhl (1973) and Annika Mombauer (2013) show that Germany was inclined to risk trying to achieve world power status through conquest: a gamble that Germany’s Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg (Fig. 2) described, when it went awry, as a ‘House of Cards’.

3. Kaiser Wilhelm II

4. Gottlieb von Jagow, Germany Secretary of State

5. Helmuth von Moltke (the younger): Chief of German Staff

A handful of German leaders: the German Emperor and Prussian King, ‘Kaiser’ Wilhelm II (Wilhelm II) (Fig.3), Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the Imperial German Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister, 1909-1917 (Bethmann Hollweg), Gottlieb von Jagow (Fig.4), the Secretary of State in the Auswärtiges Amt, 1913-1916 (Jagow) and Helmuth von Moltke (Fig.5), the Chief of the German General Staff 1904-1914 (Moltke), in particular, were inspired by, reading about, dreaming of, and planning ways to achieve their ambitions that ‘challenged the status quo in three ways: colonial, naval and economic’.

6. Conrad von Hötzendorf, Chief of General Staff, Austro-Hungarian Army

Whilst in Russia, a military response and opportunity to support Serbia manifested itself, firstly, the longer Austro-Hungary’s Chief of Staff Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf (Fig. 6) procrastinated and secondly, because French President Raymond Pointcaré (France) would actively support his ally Sergie Sazanov, the Russian Foreign Minister (Russia), thus implicating both the Russian and French leadership in the causes that led to the outbreak of war.

7. French President Raymond Pointcaré

8. Russian Foreign Minister Sergie Sazanov

The German leadership used the excuse of Franz Ferdinand’s murder in Sarajevo in June 1914, Moltke’s ‘slogan for a great war’, to risk a belligerent and acquisitive policy, firstly by bolstering Austria-Hungary against Serbia with a ‘blank cheque.’

9. Prince Lichnowsky, German Ambassador in London.

This was misguided; Jagow’s excuse to Karl Max Prince von Lichnowsky (Fig. 9), German Ambassador in London 1912-14 (Lichnowsky) was that this somehow kept the balance of power. Wars are instigated by people, not countries. When we personify Germany, Britain, France or Russia we mean a few leaders with executive power. In Germany, this meant kaiser Wilhelm II, the Reich’s Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, Jagow and Moltke; they are the reason Britain went to war in 1914.

Due to the nature of the German constitution Wilhelm II, a constitutional monarch like Britain’s, held too much power in the burgeoning German Empire and had influence that tipped then slid others towards conflict with Germany’s neighbours.

10 The British Empire in 1937: Not so different 23 years previously

Wilhelm II held the view that Germany deserved and required the status of a Great Power like that of the British Empire (Fig. 10). Used to viewing with envy, for example, the scale and grandeur of the British Fleet in his youth, Wilhelm II, a grandson of Queen Victoria, whatever the consequences and however it could be achieved, desired that Germany too should have such a fleet, something he was able to progress through Grand-Admiral von Tirpitz, State Secretary of the Reich Navy Office (Tirpitz), and by finding a way to get around budget restrictions imposed by the Reichstag; something that the then Reich Chancellor Bülow assisted with by removing Wilhelm II’s sentimental references to his youth spent in Plymouth in a proposal document, thus indicating how those around Wilhelm II would compensate for his failings as a politician and diplomat where there was, according to Lichnowsky, a preponderance of, ‘the politics of sentiment, not Realpolitik’.

11. Grand-Admiral von Tirpitz

Although a constitutional monarchy, Wilhelm II wielded power with few checks. In the case of the kaiser this was unfortunate as he wished upon himself either the role of a great Prince of Peace ‘Friedenskaiser’ or of a great warlord ‘Obersterkriegsher’. Wilhelm II would oscillate between the two perspectives, tipping him swiftly, depending on the circumstances or his company, from being in favour either of war or of peace and thus leading to a foreign policy that Lichnowsky later described as ‘either, or’. Wilhelm II’s passions could not help but influence others, according to Röhl, for example, after 5 July 1914 ‘the tub-thumping voice of Wilhelm II became one of the most effective weapons in the hands of those statesmen in Vienna who were recklessly playing with war’. While according to Sean McMeekin Wilhelm II’s ‘incandescent rage over Sarajevo gave way to recklessness’. Two weeks later on 28 July 1914 Wilhelm II, feeling certain that Austria-Hungary could be satisfied by Serbia’s overall compliance to the ultimatum presented as a result of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand believed that ‘every reason for war drops away’.

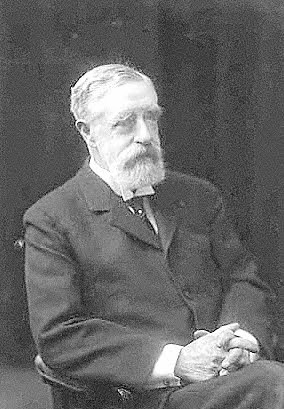

12. Sir Edward Grey, British Foreign Minister

It was in response to such extreme oscillations that Britain’s Foreign Minister, Sir Edward Grey (aka Britain) tried to find a response that would maintain peace; though his prevarications and desire to see the British Empire initiating rather than following suggestions, for example an alliance of the powers pushing Austria-Hungary to resolve its situation with Serbia through mediation without Germany’s interference, may have stifled one of the few opportunities to avoid general war. Nonetheless, the undercurrent, in Germany, was and had been belligerent for some years, planning for war, not peace, as was apparent in the conference Wilhelm II called for on 8 December 1912 that Bethmann Hollweg described as a ‘War Council’.

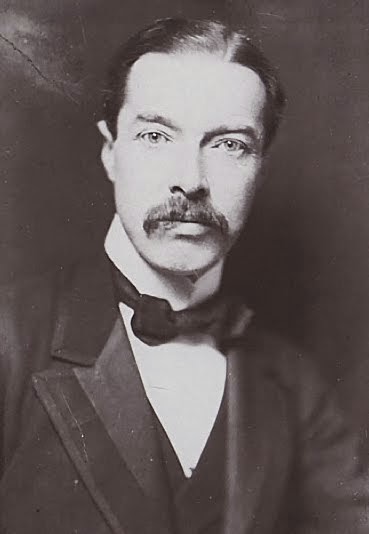

13. Viscount Richard Haldane, British War Minister (1905-12)

At this conference Wilhelm II reported on what Viscount Richard Burdon Haldane (Fig. 13), British Minister of War, 1905-1912 (Haldane) had told Lichnowsky about Britain’s view of Germany. Wilhelm II in his opening address talked of the state of preparedness of the German army and navy. According to Röhl, Germany had wanted, or at least had expected, a war for some years. Another example of the Wilhelm II’s state of mind and intent are his marginal notes (Fig. 14) . These ‘marginalia’ were so influential, that differences of opinion in the Auswärtiges Amt could, according to Geiss ‘swing round wholly and unreservedly to the harsh course ordered by the kaiser’.

14. Heinrich Leopold von Tschirschky und Bögendorff, the German Ambassador in Vienna.

In a telegram between Heinrich Leopold von Tschirschky und Bögendorff (Fig. 14), the German Ambassador in Vienna, 1907-1916 to Jagow, for example, from Vienna, 24 July 1914, Wilhelm II wrote that ‘Austria must become preponderant in the Balkans … otherwise there will be no peace’.

15. Wilhlem II’s marginalia

While on the 29th July, Lichnowsky, reporting on a visit to the British Foreign Secretary, Grey regarding Britain’s desire for mediation and the suggestion that Austria confine herself to occupying Belgrade Wilhelm II’s marginal note handwritten alongside Grey’s proposal, would, according to the kaiser result in Germany leaving ‘Austria in the lurch as if we were common as dirt and Mephistophelian!’ And then, throughout the telegram from Lichnowsky to Jagow, on the 1st August you are left with the impression that Wilhelm II’s excitable ‘marginalia’ must have been fuel to hawks.

16. Leopold count Bertchold von und zu Ungarshitz, Austria-Hungarian Foreign Minister

After the presentation of Austria-Hungary’s ultimatum by Leopold count Bertchold von und zu Ungarshitz, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister (Berchtold) to Serbia, and its aftermath, Wilhelm II made his views of the proposed conferences emanating from Grey clear and Wilhelm II was not the only German leader whose right-wing conservatism inclined the country towards conflict. Bethmann Hollweg’s will and actions, in his own words ‘like a house of cards’ were to build a position against which Britain had to act. Britain, in this respect went to war because Germany dared to try aggression to achieve its aims once unrealistic and bungled efforts to secure Britain’s neutrality in 1914 had failed. Such diplomatic ineptitude was no clearer than when Bethmann Hollweg called in Britain’s ambassador, Sir Edward Goschen (Fig.17) on the evening of Wednesday 29 July 1914 and made ‘a diplomatic blunder of the first order’ by passing remarks respecting the integrity of Belgium after a war that was yet to commence.

17. Sir Edward Goschen, British Ambassador in Berlin.

Bethmann Hollweg and Wilhelm II did not act alone, there were others in the German leadership and administration, as well as in Austria-Hungary, whose collective machinations led Britain to go to war in 1914: Jagow and Moltke drove Germany’s aims while in Austria-Hungary Franz Freiherr Conrad von Hötezendorf, Chief of the General Staff, 1906-1911 and 1912-19176 (Conrad) was equally belligerent, demonstrated by a career of warmongering against Serbia. Jagow, as early as December 1912 had said that he wasn’t against war; to Lichnowsky he took the view, like that of Wilhelm II, that Austria was weak and falling behind as a power in the Triple Alliance. Then, by way of example of his continued belligerence, after the devious way in which the Ultimatum was presented to Serbia Jagow then urged Austria to begin the war as soon as possible in order to ‘knock the bottom out of the attempts at reconciliation’. He wouldn’t stand for one of Grey’s conferences which according to Jagow, would be a ‘court of arbitration’, where the ‘timid would win through’ and in any case it was ‘Austria-Hungary’s not Britain’s nor Russia’s business. Jagow then failed to treat Grey’s initiative for mediation with any degree of urgency waiting until two hours after the time limit on the Ultimatum had expired whilst making it clear to Austria-Hungary of his tacit refusal to consider Grey’s offer. On the other hand Jagow tried to impress upon Britain that he had given the Austrian’s immediate and positive indication that he supported the British initiative. On the 25 July 1914, during a series of exchanges with Lichnowsky, Jagow insisted, hypocritically given Germany’s involvement through giving Austria-Hungary a ‘Blank Cheque’ to tackle Serbia firmly, that the ‘matter must be localised by the non-interference of all Powers’.

Moltke, was another of the German belligerents. There’s evidence of this in the Moltke-Conrad Agreement of 1909 which indicates how clear Moltke had been on how a war might play out. While in the War Council of 8 December 1912 Moltke took the view that ‘war is unavoidable sooner or later’. Then, to avert potential mediation through conference rather than sticking to Conrad’s plans for Austro-Hungarian action by the 12 August 1914, Moltke informed Lt. Colonel Biernerth the Austrian-Hungary Military Attaché in Berlin to mobilise. Moltke pushed for war throughout July 1914 because he believed that victory for Germany was possible and desirable.

According to Geiss other belligerents in Germany included leading officials in the Foreign Ministry, Count Hoyos, Forgach and Macchio in particular, and on the military side Baron Conrad von Hötzendorf Chief of the General Staff, Kribatin, General Potiorek the Governor of Bosnia-Herzegovina. It was German Imperialism and ‘Wilhelmine Welpolitik’, that according to Giess provided the latent tensions. Germany, in contrast to its agrarian neighbours Austria-Hungary and France, was an industrial force with a rapidly expanding population. Unified under the Prussian Bismark only 40 years earlier, by the turn of the century, as Hans Deltbruck put it in November 1899, ‘we want to be a world power’ achieved ‘with England means peace; against England means – through war’. Whilst Britain could tolerate a degree of Austro-Hungarian hegemony in the Balkans, it could not tolerate Germany’s potential hegemony of continental Europe. As Haldane had said to Lichnowsky ‘England could not tolerate Germany’s becoming the dominant power on the Continent and uniting it under her leadership’. Geiss believes that as one of the most powerful conservative forces in the world the German Empire would ‘uphold conservative and monastic principles by any means against the rising flood of democracy, plus its Weltpolitik, made war inevitable’ . It was born out of Germany’s fear of encirclement and of Russia’s burgeoning might, that Russia’s army was on track to become huge and that along with improved communications could by 1917 be an overwhelming threat.

18. The Balkans after the First Balkan War

The murder of Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 by Serbian fanatics should have no more brought Britain into armed conflict in continental Europe than the First and Second Balkan Wars (1912/1913). Before 1914 the principle of national self-determination directly threatened the Ottoman Empire and caused the First Balkan War against Turkey. Here, at the edge of Europe, with the desire for national self-determination being achieved at a cost to the Ottoman Empire the very same movement threatened Austria-Hungary, itself ruled by a monarchy that clung to its dynasty with its threadbare grasp on its multivarious peoples. In July 1914 Jagow told Lichnowsky that as a result of her lack of energy Austria was ceasing to count as a Great Power and weakening their Triple Alliance. And so it is that Germany turned a defensive alliance into an offensive one with its aim to achieve ‘Weltmachstellung’ (world power). Britain went to war in 1914, sooner and then again later in 1939, against this enactment of a desire in the German leadership for Germany and Germans to be part of a world power.

Understanding why Britain went to war in 1914 necessitates understanding why Germany left Britain with little choice – this cuckoo in the European nest wanted to dictate to all on the continent with Britain a tame ally or at least neutral. Britain had historically always acted against a single power dominating continental Europe. Lichnowsky’s insightful thoughts on the nature of foreign diplomacy compares Britain to a step by step approach of ‘partly, partly’ while in Germany their policy had been ‘either, or’. This is how Britain went to war in 1914 with Grey’s cautious and negotiated steps as Lichnowsky described in 1928.

19. Sir Eyre Crowe, Assistant Under-Secretary of State

Whilst Britain was reluctant to take part in an armed conflict and Serbia doubted how it would cope against Austria-Hungary without Russia’s support, in France and in Russia, war was seen as an option. Lichnowsky felt that ‘Britain’ did everything to avoid war. ‘It would have been absolutely insane to precipitate it’.Such efforts at mediation were delayed, ignored, obfuscated, discombobulated and stonewalled by the likes of Bethmann Hollweg, and spurred on by the albeit oscillating and sentimental politically inept Wilhelm II. A coalition cabinet of Liberal and Conservative politicians governed Brtiain, with Grey, the Foreign Secretary guided and advised by experienced and informed career civil servants, ambassadors and military leaders such as Sir Eyre Crowe (Fig. 19), Assistant Under-secretary of State in the British Foreign Office (Crowe), Sir George Buchanan, Sir Horace Rumbold and Sir William Nicholson.

Britain, with Grey pivotal, could not have known or believed how duplicitous Germany could be, though expert insight and analysis had been and would be provided by Crowe: Germany had ambitions and the means for aggrandisement both in Europe and Africa. ‘Either Germany is definitely aiming at a general political hegemony and maritime ascendancy’, Crowe advised in his memorandum of 1 January 1907 ‘Germany distinctly aims at playing on the world’s political stage a much larger and much more dominant part than she finds allotted to herself under the current distribution of material power. Here Crowe elucidates the dichotomy that was this fledgling cuckoo at the beginning of the 20th century: on the one hand a 20th century commercial and cultural powerhouse, on the other a 19th even an 18th political entity where the likes of Bethmann Hollweg, according to Erdmann could dream up an ‘eighteenth century cabinet war’.

According to Lichnowsky, writing in 1928, from his earliest dealings with Grey, and having spoken to Haldane he ‘repeatedly received hints to the effect that England could not remain an idle onlooker in a European war’. For the German leadership to believe that Britain would remain neutral flies in the face of the diplomatic reports they received from Lichnowsky who suggested that ‘We required [Grey] to make the Austrian standpoint as much his own as we did’. Repeatedly Grey took the initiative to see if the issues could be resolved. For example Lichnowsky to Jagow 25 july 1914, Grey’s and therefore Britain’s problem was that he ultimately came up against Germany’s fait accompli. The final days of July 1914 and the first days of August show what Grey did to try to avoid Britain having to take part in a continental war. Röhl describes the end of July 1914 as,

‘A race between the Powers in their moves to mediate and Germany in her endeavour to bring Austria-Hungary into the war at the earliest possible moment and so give still great force to the fait accompli with which the world was to be confronted’.

On the 26 July 1914 Grey’s proposals for a four power conference would involve those countries which were not, he believed, directly involved in the pending conflict between Austria-Hungary and Serbia: Britain, France, Italy and Germany. To this end Grey instructed Sir Edward Goschen, British Ambassador in Berlin (1908-1914), to promote ‘the direct exchange of views between Austria and Russia’ not realising that Austria was already at war with Serbia and that Russia had begun premobilisation. Although the Great Powers desperately tried to prevent the local war against Serbia as the best means of averting a major one (for example, Telegram 199. 27 July, Jules Cambon, French Ambassador in Berlin to Jean-Baptiste Bienvenue-Martin, the acting French Premier/Foreign Minister from 15th to 29 July 1914), on the proposal by England for Germany to join the cabinets of London, Paris and Rome, ‘to prevent hostilities between St. Petersburg and Vienna’.

20. Jules Cambon, French Ambassador in Berlin

Although we know that the duplicitous Jagow while saying that ‘he was disposed to join the Powers and do all he could to preserve peace’, had only a few hours earlier expressed his regret to Berchtold that military operations against Serbia were ‘too long drawn’ and that ‘proceeding without delay to place the world before a fait accompli’ was vital.

The German Government again on the 28 July 1914 steadfastly rebutted all attempts at mediation – to have participated in mediation would have soon revealed the extent of Germany’s duplicity.

On the 29 July 1914 the British Cabinet met after which Grey sent for Lichnowsky repeated his suggestion that Germany take part in mediation … ‘à quatre’ On the doctored version of the original telegram that Jagow put before Wilhelm II, one of the kaiser’s marginal notes states a preference for England making it clear to Russia and France that she will not side with them, which that night, early on the morning of 30 July 1914 turns into Bethmann Hollweg’s bid to secure British neutrality. Grey in turn explains in a conversation with Cambon, French Ambassador in London, 1898-1920, that in a general conflict Britain would not be able to remain neutral, though he explained also that there could be no guarantee of intervention by Britain until the position of Belgian neutrality was understood. Paul Cambon now asked Grey to reconsider their correspondence in 1912 and Raymond Poincare, the French Premier, attempted to make it clear to Sir Francis Bertie, Ambassador to Paris, that only an unequivocal of England’s support could save the peace.

Come 31 July 1914, Grey continues to talk peace and mediation. Nor could Grey undertake any definite agreement learning that Russia had ordered a complete mobilization of her fleet and army, ‘I still trust that situation is not irretrievable’ he said while Germany, according to Grey, Germany did not expect Britain’s neutrality. Whereas in fact, due to the mistaken weight Wilhelm II gave to a letter of 28th July 1914 from his brother Prince Heinrich, Prince of Prussia. It was Grey, by refusing to take the neutral route that caused Bethmann Hollweg’s ‘House of Cards’ to collapse. Britain went to war in 1914 because Germany had staked too much on Britain’s neutrality; under the circumstances, as the conflict escalated, Britain, the erstwhile super power and empire, was quite unwilling and unable to remain neutral.

On 1 August 1914, in a last-ditched effort to conjure up the impossible Grey had a telephone conversation with Lichnowsky that the Prince interpreted as an assurance of Britain’s neutrality in the event that France remained neutral too, though what Grey had intended to mean, some authors contend, was that he had meant to imply that Germany too would remain neutral.

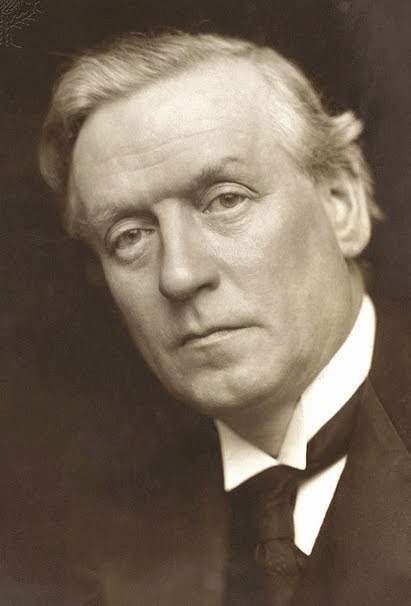

21. Herbert Asquith, British Prime Minister

There were other internal reasons why Britain had not been early to make a firm stand against Germany, not least division in the British cabinet that risked a collapse of the British Government or taking a non-interventionist route, therefore having by the time the cabinet met, the support of the Unionist Part was crucial to the policy of Grey and Herbert Asquith (Fig. 21), British Prime Minister 1908-1916.

22. Henry Wilson, Director of Military Operations

Even more importantly, Henry Wilson, British General, Director of Military Operations 1910-1914 (Fig. 22) had been successful in securing interventionist Tory pressure on the Liberals. Grey said he would resign if Viscount John Lord Morley of Blackburn, Lord President and the Council and Cabinet Minister 1910-14 (Fig. 23) and the ‘Little Englander’ faction desired ‘an uncompromising policy of non-intervention’.

23. Viscount John Lord Morley

At this stage on 1st August the cabinet still said no to Churchill, but by 3 August 1914, with the most vociferous non-interventionists gone, the cabinet approved Churchill’s previous mobilisation of the Fleet. And now, according to Cambon, if Britain would fight at sea, they would fight on land as well. Speaking in the House of Commons that day Grey declared that ‘if Britain stands aside, forfeiting her Belgian Treaty Obligations’, then we would ‘sacrifice our respect and good name and reputation’. Although Grey had, according to Lichnowsky been, ‘a force for peace’ with Germany’s invasion of neutral Belgium removing all doubts and barriers from Britain’s apparent and from Germany’s point of view plausible and desirable neutrality, Britain went to war with Germany.

24. H G Wells: The war that will end all war.

The usually misquoted H.G. Wells’ phrase, ‘the war that will end all war’ – the title to a pamphlet he wrote in November 1914, expresses what all the leaders of the combatants understood – that this would be a war on a scale like none that had gone before, a risk the German leadership wanted to take, opening a Pandora’s Box. Grey, and others, such as Viviani understood this which explains their kind of diplomacy that to some appeared then and since as evasion or indecision, whereas the evidence in the original documents shows that actions were designed to achieve peace against the odds. Although it was the invasion of aliens that H.G. Wells (Fig. 24) wrote about in his fiction, several other authors had written about a fictional invasion of Britain by Germany, something that initially the cabinet and British Military leadership planned for and what was seen as an eventuality should Germany have been successful in conquering France and Russia. In its position as the dominant and established World Power, it was the British Empire that felt it had to meet the obligation to support France, not least because consideration had been given to alternative outcomes: France and Russia defeating Germany leaving the defensive alliance in tatters and other parts of the British Empire vulnerable.

25. Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener

Ultimately Britain alone did not ‘go to war’, but rather the British Empire, with Kitchener (Fig. 25) as its military leader, a stalwart of successful colonial rule in India and of battles in Sudan and Southern Africa, with dominion and colonial forces to call upon, blocked Germany’s way to Paris. Having paved the way for seeking common ground on foreign policy in 1904. With Britain’s own issue of internal national self-determination to manage, the question of Irish Home Rule and the Protestant countries of the north, postponed and with parliament’s and the cabinet’s support to do so, Britain presented Germany with its ultimatum.

Britain had not declared her position too late, rather she had left the door open for as long as possible hoping for mediation.

The extent to which German leaders, Bethmann Hollweg and Jagow lied about Germany’s role and actions in relation to pushing Austria-Hungary into war with Serbia and deliberately stymied British efforts to bring the Powers to conference has only subsequently been fully realised. Though the evidence was lacking, advice and insights from the likes of Buchanan, Rumbold, Nicholson and Crowe from Britain, as well as from Pointcare and Sazanov from France and Russia respectively, must have come close to confirming Grey’s fears regarding Germany’s desire to be and to prove that it was a World Power.

26. Europe in 1914 (Maps.com)

Where Germany was belligerent, Britain sort peace; where Germany was devious, Britain was politically correct; where Germany was inept, Britain was a paragon of considered diplomacy; Germany was blunt while Britain was coy, and whereas Germany’s leaders worked in the cabal of monarchic rule Britain’s leaders worked as part of a cabinet and reported to Parliament. Ultimately, Britain could not remain indifferent ‘when all Europe was in flames’ Whilst compared to other neutral states (See map Fig. 26), be it the Netherlands, Sweden or Spain, Britain and its Empire could and had to act according to its status, having the means to do so with the Fleet and the British Expeditionary Force and having, with German’s breach of Belgian neutrality, and cabinet support, not without resignations and abstentions, the legal means to do so.

READING LIST

Audio-Rouzea, S and Becker, A “14-18 Understanding the Great War” (2000) Hill & Wang

Clark, C (2013) “The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914”. Penguin eBook.

Geiss, I (editor) “July 1914: The Outbreak of the First World War. Selected Documents”. (1967) Norton Paperbound

Geiss, I (1976) “German Foreign Policy 1871-1914”. Routledge Direct Editions

Lichnowsky, K.M. Prince von (1928) (2014 print on demand, copy of the original) “Heading for the Abyss”. Translated by Sefton Delmer. Kessigner Legacy Reprints. Payson & Clarke

MacMillan, M (2013) :The War that ended Peace: How Europe Abandoned Peace for the First World War”.

McMeekin, S (2013) “July 1914: Countdown to War”. Icon Books eBook.

Mombauer, A (2002) “The Origins of the First World War”.

Mombauer, A (editor and translator) (2013) “The origins of the First World War: Diplomatic and military documents”. Documents in Modern History. Manchester University Press.

Renouvin, P (1925) (2014 an authentic reproduction of the original text) “Les Origines Immédiates de la Gueere”. (28 Juni – 4 Aoüt 1914) Gale MOML Print Editions

Röhl, J.C.G “The Kaiser and his Court: Wilhelm II and the Government of Germany” (1994) The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge

Röhl, J.C.G (edited and introduced by) (1973) “1914: Delusion or Design: the testimony of two German Diplomats”. St. Martin’s Press

Strachan, H “The First World War” (2003) Simon & Schuster

Strachan, H (2001) “The First World War: Volume I: To Arms”. Oxford University Press. eBook.

Wells, H.G. “The war that will end war” (1914) Reprint 2014 The Library of Congress and Amazon.co.uk

Further Links

Ten interpretations of who started the First World War

What can historians tells us about the concept of Europe?

Who ignited the First World War?

Why did Britain go to war in 1914? (In 65 words)

Britain went to war in 1914 because a handful of belligerent political leaders in Berlin exploited the murder of the Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand to pursue Germany’s long-held desire to be a world power: their machinations, deviousness, obfuscations and at times ineptitude and delusions, led Britain’s leaders after considerable efforts at mediation, to go to war with Germany, after they had invaded neutral Belgium.

Why did Britain go to war in August 1914?

IN BRIEF

Britain was a global empire content to rule the waves and trade with her dominions and colonies, not least with the subcontinent of India. Where a choice needed to be made it was better to have Russia and France on friendly terms, especially as Germany post-Bismarck under kaiser Wilhelm II was seeking its ‘place in the sun’ – as a world power, dominant in Europe with a vast swathe of central Africa too. There was no need for the murder of archduke Franz Ferdinand to escalate however Germany, through the kaiser and Reich Chancellor pushed Austria-Hungary into what they at first hoped could remain a localised war, or at least one against Russia, or maybe against France to, but ideally not with Britain as well. Despite Germany’s lies and misjudgments, Sir Edward Grey did his utmost to bring the conflicting parties to conference: neither Austria-Hungary or Germany was having anything of it – they wanted war, Germany to resolve once and for all its fears on encirclement and Austria-Hungary to prove to all minority groups in its fragmented empire that it would stand up to anyone seeking national self-government. Britain did not have a cabinet agreement to enter the war until after Germany had invaded Belgium, however close talks and agreements were with both France and Germany. Nor in the British Expeditionary Force did it have a continental army – though it could and did very quickly draw from the dominions and colonies, as well as from volunteers.

SUMMARY

Britain went to war, reluctantly, in 1914 in response, once all efforts at mediation had failed, to the belligerent machinations of specific people in the Berlin leadership who exploited the murder of the Austro-Hungarian heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, no matter the risk of turning a local conflict into a world war, to challenge the status quo and so earn through conquest a position as a World Power.

Britain was reluctant, as were France and Russia, even Serbia to an armed conflict. Britain, expected or at least hoped to play a neutral role by Germany, through its Foreign Minister Sir Edward Grey and guided by the cabinet of a coalition Government of Conservatives and Liberals, did its utmost to mediate, through proposals for conferences and through direct and indirect diplomatic channels, in particular through briefing the German Ambassador in London, Prince Lichnowsky. Such efforts at mediation were delayed, ignored, obfuscated and stonewalled by the likes or the Reich’s Chancellor Bethman Hollweg, and Jagow, spurred on by the albeit oscillating and sentimental diplomatically inept German monarch, kaiser Wilhelm II. Documents identified for the purposes of explaining the actions, decisions and feelings of the participants in the lead up to what became a world war by Immanuel Giess in 1965 and Annika Mombauer some fifty years later, clearly show that Germany was inclined to try its hand, an apt metaphor that indicates the gamble they took, to escape the impasse, let alone the containment or encirclement which certain German leaders felt was keeping Germany back from its rightful place on the world stage.

Understanding why Britain went to war in 1914 necessitates understanding why Germany left Britain with little choice – the Cuckoo in the European nest wanted to dictate to all on the continent and would have happily left England on the other side of the Channel. There are three parts to this understanding: Germany’s rapid rise and maturity as an industrial nation contrasting with an immaturity or at best a splenetic political form of government; the position, character and demands of a handful of German leaders who dreamt of, planned and then willed continental if not world war and the efforts, and the ramifications of the ultimatum presented to Serbia by Austria-Hungary at Germany’s behest which led to diplomatic and Diplomatic efforts by Britain to prevent the localised war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia that would lead, the politicians knew, to a far wider conflagration.

IN A BIT MORE DETAIL

Britain went to war, reluctantly, in 1914 in response, once all efforts at mediation had failed, to the belligerent machinations of specific people in the Berlin leadership who exploited the murder of the Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand, no matter the risk of turning a local conflict into a world war, to challenge the status quo and so earn through conquest a position as a World Power.

Britain was reluctant, as were France and Russia, even Serbia to take part in an armed conflict. Britain, expected or at least hoped to play a neutral role by Germany, through its Foreign Minister Sir Edward Grey and guided by the cabinet of a coalition Government of Conservatives and Liberals, did its utmost to mediate, through proposals for conferences and through direct and indirect diplomatic channels, in particular through briefing the German Ambassador in London, Prince Lichnowsky. Such efforts at mediation were delayed, ignored, obfuscated and stonewalled by the likes or the Reich’s Chancellor Bethman Hollweg, and Jagow, spurred on by the albeit oscillating and sentimental diplomatically inept German monarch, kaiser Wilhelm II. Documents identified for the purposes of explaining the actions, decisions and feelings of the participants in the lead up to what became a world war by Immanuel Giess in 1965 and Annika Mombauer some fifty years later, clearly show that Germany was inclined to try its hand, an apt metaphor that indicates the gamble they took, to escape the impasse, let alone the containment or encirclement which certain German leaders felt was keeping Germany back from its rightful position on the world stage.

Understanding why Britain went to war in 1914 necessitates understanding why Germany left Britain with little choice – this Cuckoo in the European nest wanted to dictate to all on the continent and would have happily left England on the other side of the Channel. Britain had historically always acted against a single power dominating continental Europe so a pressure point, if not conflict formed as Wilhelmine Weltpolitik moved from being an idea to a modus operandi.

There are three parts to this understanding: Germany’s rapid rise and maturity as an industrial nation contrasting with an immaturity or at best a splenetic political form of government; the position, character and demands of a handful of German leaders who dreamt of, planned and then willed continental if not world war and the efforts, and the ramifications of the ultimatum presented to Serbia by Austria-Hungary at Germany’s behest which led to considerable diplomatic and Diplomatic efforts by Britain to prevent the localised war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia that would lead, the politicians knew, to a far wider conflagration.

Germany, in contrast to its agrarian neighbours Austria-Hungary and France, was an industrial force with a rapidly expanding population; its leadership felt it needed room to grow into. Unified under the Prussian Bismark only 40 years earlier, by the turn of the century, as Hans Deltbruck put it in November 1899, ‘we want to be a world power’ which achieved ‘with England means peace; against England means – through war’. Britain, in this respect went to war because Germany dared to try aggression to achieve its aims once bungled efforts to secure Britain’s neutrality in 1924 failed.

Kaiser Wilhelm II felt Germany deserved and required the status of a Great Power too. Although a constitutional monarchy, like Britain, in Germany the kaiser wielded power with few checks. In the case of the kaiser this was unfortunate as this wilful man wished upon himself the role of a great Prince of Peace and a great warlord. (Geiss, 1965). His oscillations between the two could be tipped in favour of war as the Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg managed, for example not allowing the kaiser to apply the brakes in the final moments before the outbreak of war. () Whilst according to Michael Freund, Franz Fisher’s made Bethman Hollweg out as being like Hitler is somewhat extreme, it is nonetheless the case that it was The Reich Chancellor’s will and actions, in his own words the ‘house of cards’ that he constructed, that built a position against which Britain had to act, in the final analysis when Germany breached Belgium neutrality, though it was to support France that Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Minister, with the agreement of a split Conservative/Liberal Cabinet, presented Britain’s ultimatum to Germany. Bethmann Hollweg did not act alone, the machinations of both Jagow and Moltke significantly drove Germany’s aims to force Austria-Hungary into a local war with Serbia, even though, indeed because, this would bring Russia into the fray and in turn initiate the Schlieffen plan that required the massive and equipped German army to attack France through Belgium. Such behaviour had been in the air since the end of the previous century () and on the cards since 1907 (). It was born out of Germany’s fear of encirclement and of Russia’s burgeoning might (). Fears felt by those in power in a Reich that lacked any constitutional provision for formal deliberation of such problems and now devoid of Bismarkian ‘Realpolitik’ (), the ‘politics of sentiment’ () the way the kaiser’s rule is described. Lichnowsky described to Bethmann Hollweg Jagow’s ‘misguided’ belief that Russia would stay out of the war for a few years yet – but it was lack of guidance, or the ability or means to listen to and act on advice that allowed a handful of people in Germany’s Ministry’s to believe the outcome of their actions and the subsequent war would be an mighty Germany at the centre of Europe and of Africa.

The Sarajevo Crisis brought about by the murder of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire should have no more brought Britain into armed conflict in continental Europe than the First and Second Balkan Wars. () Here, at the edge of Europe, with the desire for national self-determination being achieved at a cost to the Ottoman Empire () the very same movement threatened Austria-Hungary, itself ruled by a monarchy that clung to its dynasty with its threadbare grasp on its multivarious peoples and allied to the second most conservative nation after Czarist Russia, namely Germany. The murders of FF and SC gave Moltke the ‘slogan for a great war’: the excuse to flex considerable muscle. Britain, with the Foreign Minister Grey pivotal, could not have known or believed how duplicitous Germany could be, though expert insight and analysis had been and would be provided by Sir Eyre Crowe: Germany had ambitions and the means for aggrandisement both in Europe and Africa. ‘Either Germany is definitely aiming at a general political hegemony and maritime ascendancy’, Crowe advised in 1907, ‘threatening the independence of her neighbours and ultimately the existence of England, or … is seeking to promote her foreign commerce, spread the benefits of German culture’. Here Crowe elucidates the dichotomy that was this fledgling cuckoo at the beginning of the 20th century: on the one hand a 20th century commercial and cultural powerhouse on the other a 19th even an 18th poltical entity where the likes of Bethmann Hollweg, according to Erdman () could dream up an ‘eighteenth century cabinet war’. Repeatedly Grey took the initiative to see if the issues could be resolved, the most important proposal on 26th July for a four power conference in London between those countries which were not directly involved: England, France, Italy and Germany (g93,94). Germany refused thinking of it as tantamount to an ‘Aeropagus before which Austria would be held’ (g90) With delay only likely to play into the hands of the mediators gp. 270 Moltke took things into his own hands and informed Lt. Colonel Biernarch the Austrian-Hungary Military attaché in Berlin to mobilise immediately.

Metaphors on the one hand help with ‘meaning making’ and are used to help explain the complex even though they evoke the bias of their authors. Even a phrase as seemingly innocuous as ‘Britain goes to war’ suggests something far less troubled, debated over and contested – war, especially on the scale and for the duration expected – requiring millions of men and many years rather than a few months to resolve, was the last thing that Britain, let alone France, Russia or even Serbia desired. In this respect Britain did not so much go to war, as have war thrust in her face with the fait accompli the German leadership, Jagow in particular, pulled off by getting Austria-Hungary to get on with what her belligerent partner wanted and open the conflict with Serbia by bombarding Belgrade. Buchanan suggested to Grey that Britain would be ‘dragged’ into war, a century later the historian Christopher Clark (2011) describes how the countries ‘sleepwalked’; reading the original documents however you see that Britain and the other leading nations made a ‘conscious decision’, Geiss’s phrase (1965) and that in Britain’s case this was to make a stand with France against an aggressive Germany that felt that duplicity rather than diplomacy, and conflict rather than conference, was the way to achieve the aims of a nation’s leadership. Britain took a reasoned, and for the times the only course of action possible, when every conceivable effort to prevent war had failed; ‘going to war’ was the consequence of failing to postpone the ‘local’ war and get the parties to mediate – an impossible task given that only Germany had the means to start, delay or avert this ‘localised’ war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia.

Britain could act, having the immediate means to do so with the Fleet and the British Expeditionary Force and having, only with German’s breach of Belgian neutrality, Cabinet support, not without resignations and abstentions, to do so.

What Grey did, by committing, was to refuse to remain neutral as Germany had hoped, and so to remove one of the cards that would cause Bethmann Hollweg’s ‘House of Cards’ to collapse (g340) – the neutrality of the British Empire. Moltke would get the ‘showdown’ he had desired, to use another metaphor that places Britain and Germany like a couple of barefist fighters in the ring, a metaphor that puts at arm’s length the reality, brutality, and totality of what the players knew would be calamitous. The usually misquoted HGWells’ phrase, ‘the war that will end all war’ – the title to a pamphlet he wrote in November 1914, expresses what all the leaders of the combatants understood – that this would be a war on a scale like none that had gone before, a risk the German leadership wanted to take, opening a Pandora’s Box () that a century later remains ajar. Although it was the invasion of aliens that HGWells wrote about in his fiction, several other authors had written about a fictional invasion of Britain by Germany, something that initially the Cabinet and British Military leadership planned for and what was seen as an eventuality should Germany have been successful at conquering France and Russia on the continent. In its position as the dominant and established World Power, it was the British Empire that felt it had to meet the obligation to support France, not leadt because consideration had been given to alternative outcomes: France and Russia defeating Germany leaving the defensive alliance in tatters and other parts of the British Empire vulnerable. Ultimately Britain alone did not ‘go to war’, but rather the British Empire, with Kitchener as its military leader, a stalwart of successful colonial rule in India and of battles in Sudan and Southern Africa, with dominion and colonial forces to call upon, blocked Germany’s way to Paris. Having paved the way for seeking common ground on fireign policy in 1904 gp. 274 Paul Cambon now asked Grey to reconsider their correspondence in 1912 (g148) and Poincare attempted to make it clear to Bertie that only an unequivocal of England’s support could save the peace.

With Britain’s own issue of internal national self-determination to manage, the question of Irish Home Rule and the Protestant counties of the north, postponed and with parliament’s and the cabinet’s support to do so, Germany was presented with the British ultimatum, ironically after all the prevarications of this issue when it came to Austria-Hungary and Serbia, with a short timescale – not that there could possibly have been any further reason to hope for or expect mediation.

Britain had not declared her position too late, rather she had, in hindsight naively, left the door open for as long as possible for mediation – the extent to which German leaders, Bethmann Hollweg and Jagow purposely lied about Germany’s role and actions in relation to chivying Austro-Hungary into war with Serbia and deliberately stymied British efforts to bring the Powers to conference has only subsequently been fully realised (). Though the evidence was lacking, advice and insights from the likes of Buchanan, Rumbold, Nicholson and Crowe from Britain, as well as from Poincare and Sazanov from France and Russia respectively, must have come close to confirming Grey’s fears regarding Germany’s desire to be and to prove that it was a World Power.

Does 37 days tell the story of how Britain went to war in 1914?

This shows potential and ought to seek funding as a movie – the kind with Daniel Day Lewis and Al Pacino, Kevin Spacey and Ralph Fiennes, Liam Neeson and Andrzej Seweryn. Then add the set and location values of Anna Kerenina.

BBC One, 37 Days, March 2014.

Of course, 37 days is a questionable premise. In 1912 we nearly went to war over Morocco, locally the beginning of the war for Britain was already the Third Balkan war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. There was newr civil war in Ireland. Russia mobilised on 31st July which pushed Germany to put the Schlieffen Plan into play and invade Belgium. And then until 1916 Britain was playing a costly holding game while an army of suitable size was created and the war could be attempted on terms.

Why did Britain go to war in 1914?

Published in 1916 after Edward Morel had resigned from the British Cabinet as he found the decission to go to war untenable. He blames sculdergy at the top, secret agreements tying Britain to Russia via France, and Russian mobilization on 31st July which in turn resulted in Germany acting. Things would have been different had there been a Commons debate rather than the Foreign Office under Lord Grey being so self-determining. The crisis in Morocco in 1912 had been a close call to war too.

Who wants to commemorate the First World War?

We should use the ‘connectedness’ of Web 2.0 to buddy up with six other people each from, for example, Germany, Russia, France, Serbia, Turkey, South Africa, Newfoundland, Belgium, Australia, Portugal, Japan, Italy … and more, to take in the 37 countries that threw their people at the artillery, machine gun fire, gas and barbed wire between 1914 and 1918 and then reflect on whether we are doing enough in 2014 to prevent violent conflict on any scale, anywhere. But we should not dictate, or tut tut if the response in Germany is different to ours. This has been the problem of the 20th century in families as in politics – expecting everyone to be like you, instead of recognising that we are each so different it makes me feel lonely to think about it.

Join me by making the commemoration ‘for the people, by the people’ – commemorate an ancestor or pick a name from a war memorial or from the records, and research their story. Post your content online then generate a Quick Response code and wear this. When people ask what it is say who you want to remember and how they can find out more … and even do the same themselves.

Who caused the First World War?

If a gas shell in the mud of Paschendaele in late October 1917 represents an absolute truth regarding the First World War, especially if you are perched behind a machine gun in a pill box just a few yards away, then this truth soon shifts as time passes, the gas is released and a morning breeze first backs, then slows, then changes direction moving ever further from the moment if truth. And thus, the politicians and historians play merry with the facts, in the form of official documents, as they are offered, revealed, exposed, disguised and refuted Try pegging where any of them stand on the truth of the causes of the First World War and you’ll have flags planted in every direction with little chance of getting back to the original point. And thus we have revisionists and anti-revisionists and their reasons for writing this way or that. The simple answer is that the problem Europe got itself into in 1914 was a mess. And from the perspective of a hundred years on I look through my timetelescope and want to damn the lot of them; but that was then, and now is now.

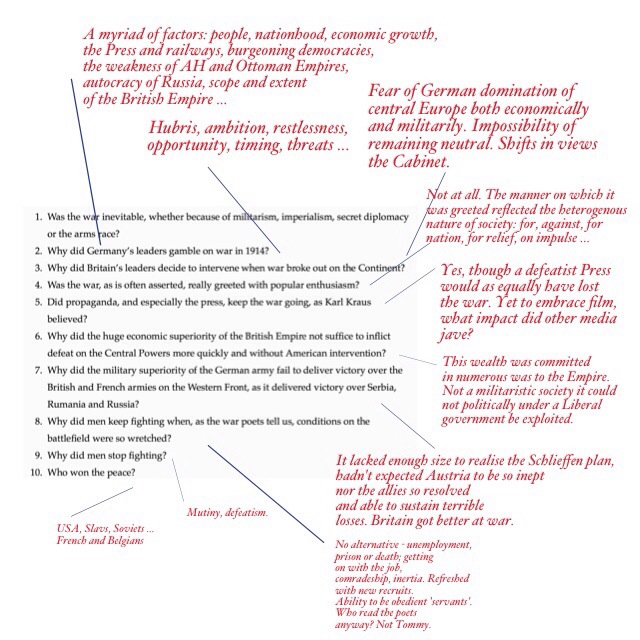

The Pity of War: Mindmap for a Book Review

Fig.1 SimpleMind Mindmap based on Niall Ferguson’s ‘The Pity of War’

I’ve now read ‘The Pity of War’ twice in a row. As I’ve gone through it I’ve highlighted passages and added notes

and tabs in Kindle. I also grabbed a few highlighted passages and put them into the iPad App ‘Studio’ to annotate and took slides from a

presentation on how to prepare a book review by Dr Pete Gray of the University of Birmingham and annotated these too.

On the second reading I created the SimpleMinds mindmap above.

This ought to be my starting point for a solid 1,000 word book review.

Further reading in the from of Books and papers of interest have been picked up along the way too.

Those to find in a university library, those acquired secondhand through Amazon or uploaded as eBooks in Kindle and papers I can find as a postgraduate student online, either through the Open University or the University of Birmingham (I am a postgraduate student at both). There are various ways I can offer the above, though the best is to download the FREE version of SimpleMinds and read it that way.

Offered with a view to sharing the views of others.

I can export it into a word file and develop the categories I already have as separate themes:

Insightful (in yellow) has some 52 notes, most referenced by Kindle Link (KL).

Do I buy the print version or go to the library and cross-reference?

Descriptors: meticulous, original, weighty, highly referenced, all sides, high brow, thoroughly researched, well read … often

intricate, taking us to detail researched by others? NOT, as he says in the introduction, a textbook or a narrative of the war.

No Trivia – nor the chronology if the war, nor countless aggregated memories of veterans, though there is a bit of poetry and some

mention of movies and TV films from ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ to ‘Birdsong’, ‘Gallipoli’, ‘Blackadder goes forth’ and

‘Ghost Road’ Bias – I wonder about this in relation to where Niall Ferguson – that he relishes a dig on the landed gentry and public

school system, their types, behaviours and hobbies, from leadership to country sports.

Debunking myths: the desire for war, the Germans to blame, the Russians to blame, militarism, German economic efficiency, not donkeys, the AEF didn’t win the war and blundered in making the mistakes of 1914, naval supremacy and ambivalence to war.

The Press – censorship, Buchanan, DORA. Finance – givernments

and bankers.

A dilletante, too thorough, comprehensive: penny dreadfuls, invasion stories, art history and drama, from Karl Kraus to Oh What a Lovely War.

Errors or mistaken emphasis: Fashoda, conjecture that Grey et al. exaggerated the threat of Germany despite intelligence, attempting to interpret stats on fatalities, wounded and prisoners, the Entente were better at killing, maiming and taking prisoners, Tommy gets angry with a Jerry prisoner, All

Quiet on the Western Front is not biography though Ferguson quotes from it as if it is. Remarque wasn’t a front line soldier. The Oxford Union as any kind of representative body for comment. That Belgium neutrality would have been breached by GB. That skilled workers lost to the war impacted our economy when women very effectively stepped in. That the EU in its current form might have emerged has GB stayed out of it. That waving Tommies are from a photo archive when they are grabs from the Battle of Somme footage.

Kinds of historian: cultural, military, diplomatic, economic.

Why was recruitment successful? Recruitment campaign, female pressure, peer and employer pressure, impulse, economic motives, and more?

Other historians and commentators:

Alan Clarke, Lidell Hart, John Terraine, Correlli Barret, Michael Howard, Norman Stone, Lafell, Bidwell, Graham, Travers, Holmes, Martin van Creveld, Dominic Graham, JMBourne, Michael Geyer, Martin Samuels, Gudmannskn, Paddy Griffith, Theo Balderston, Knaus and Hew Strachan.

With distinct sections on:

Finance and JMKeynes Writers

With a bit on poets, and rather less on films and art.

What did he leave out then?

- Women

- The Home Front

- Technological developments, especially in the air

Fig.2. A brief response to the ten questions Ferguson poses at the start of the book and attempts to answer by the end – I’m not wholly convinced.