Home » E-Learning » e-Assessment

Category Archives: e-Assessment

Learning how to communicate the key components of a Massive Open Online Course

Ideas that are encouraged to fester mature at the most inconvenient of times

Often I find that I am up in early and keen to put my thinking into practice

Currently I am trying to develop a simple notation to show, share, explain and develop online courses. During the MAODE I completed in 2013 we often used flowcharts, one with an OU software package – these could become a bit tricksy. My answer was to set up plans of MDF shelving in the garden and get out a chess set to try and show the relationships between the required components.

Common thinking is that there are three parts to creating online learning: technical, human support and, of course, us students. Technical means the platform, its ease of access and intuitive use; human support means, in the case of The OU, the course chair, associate lecturer and us student (those who are familiar with the setup and the subject matter are encouraged to, and enable to help newcomers to the ways things are done, and to the subject when you get stuck).

Prof Gilly Salmon talks us through ‘the building blocks’ of an online course

Of note is a short, charming and engaging presentation made by former OU Business School Senior Lecturer, and now Prof Gilly Salmon at Swinburne University in New South Wales. Here, like a Blue Peter presenter, she uses a set of kid’s coloured building bricks to talk us through the components required to make an online course (OU style) that works.

How Gilly Salmon uses green, yellow, blue and red building blocks to show how to plan an online course.

Green = Technical

Yellow = The students or ‘learners’

Blue = Human support (i.e. in OU Land the ‘associate lecturer’)

Red = Assessment

As I am trying to develop a shorthand, language or ‘notation’ to be able to compare and create online course, I invested in my own set of building bricks. Once again I set up a length of MDF in the garden to play around with ways to communicate the nature and order in which these components appear.

The results have been enlightening.

It is extraordinary what happens when you start to get stuff out of your head, and especially valuable not to be confined by the parameters of a piece of software: it is so easy, and so necessary, when thinking things through to be able to play around with the pieces.

Gilly Salmon’s ‘Five Stage Model’ revisited

Gilly Salmon 5 Phase Flowchart

Gilly Salmon’s ‘Five Stage Model’ for e-learning using the bricks she used in her seminal video

For simplicity’s sake, let’s say that this ‘Five Stage Model’ is for a five week module from the OU.

The bottom row of green bricks represents the Learning Management System (LMS) on which the learning appears. The technical side of things includes accessibility, web usability, reliability and good ‘design architecture’ i.e. it works well, is clear, intuitive, reliable and follows the most common user behaviours for anyone online in 2016.

The middle row of yellow bricks (and one red one) represents learner activities, from a gentle introduction to the platform to engaging in activities, which typically includes nothing more complex that watching a video, reading text and doing research or doing a multiple choice quiz. The red brick represents formal assessment: at The OU, this would be a Tutor Marked Assignment (TMA) or End of Module Assignment (EMA).

The top row of blue bricks represents the human interface between the students and the education institution, in this case The OU. Here, typically, we are talking about live and as live contact via various platforms, though it can include phonecalls, ‘online hangouts’ and even a residential component to the course. At The OU there is an assigned Tutor or Associate Lecture who ‘handles’ a group of 8-12 students. It is this practice that is impossible to scale when it comes to Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs). You cannot employ 2,000 tutors to manage 16,000 to 24,000 students. Some MOOCs of many more participants than this!

It is this component too that is increasingly blended into, or comes out of the technical side of things, or from the students themselves. Firstly, increasingly detailed and easy to use Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) answer typical enquiries that students have, increasingly the ease of use of a platform is such that little to no support from the ‘team’ or ‘Technical Help Desk’ is required. At the same time, students are formally enrolled to conduct ‘peer review’ and when several do this for each submitted assignment a grade is come to in this way. The degree of student interaction, and the benefits of collaborative knowledge construction through this, is far harder to get going and sustain without the proactive role of the tutor or a moderator. When ‘classes’ are smaller, MA and PhD students are sometimes given a role to act as a catalyst for engagement and to answer enquiries and deal with some problems.

My own take on the ‘lay-out’ of a ‘typical’ MOOC is pedagogically different.

I believe that ‘assessment’, of the micro-quiz and multiple choice variety, is a crucial component of e-learning. This is engagement that obliges participants to think, even to struggle and repeat parts of the content, until the knowledge that matters begins to stick. Gilly Salmon’s model is one for ‘distance learning’ while today, especially the MOOCs coming from Coursera, test you from the start. This might be as simple as interrupting a six minute video piece with a two question ‘quiz’. I liken this to a teacher in class pausing, putting a question then taking an answer from one of the raised hands, or picking someone out. It makes you aware that you need to listen. You want to get these questions right even if they don’t count towards anything. It is a form of light gamification, while also preparing you for an 8 or 10 or more part set of questions at the end of a component of the learning where the answers need to be right, and are based on these earlier interjections. It matters that these are a genuine challenge, that the pass mark is 80%. An easy ride isn’t one that leaves you with much recollection of what you have been studying. A tough ride, as I find, and applaud, however frustrating, requires you to do a the week (typically a couple of hours) over, and sometimes over again … until you can pass.

JFV Supported MOOC 5 Phase Flowchart

Jonathan Vernon’s take on phases of the ideal ‘Massive Open Online Course’ where constant assessment is key

Here, drawing on the wide variety of online courses I have done: creative writing, photography, web science, language learning, history, psychology, medicine and the arts, climate change and more, I have tried to envisage an ideal format. Of course, subject matter, subject level and other criteria would immediately causes adjustments to this.

My five phases are:

Technically the platform needs to be solid. This technical side now encroaches on student support, not just from FAQs, but other ways the content and technology can step in to do what a person would have done in the past (and still does in blended courses). There might be video, there might even be some kind of AI to nurture some of the many thousands of students taking a MOOC. There is some kind of testing from the start. This might be nothing more than a check that students have understood some components of the introduction, but it gives them a taste of things to come; they will be doing these ‘quizzes’ regularly. If interaction between students can be encouraged then here, as early as possible, they need to be online in a ‘social’ like environment.

The second phase gentle eases students into learning proper. The technology is a solid ‘bridge’ into the content. Support is done through the platform for the most part rather than needing to call on a person. With many thousands on a course in many times zones around the globe how can a call centre of technical people be expected to be available?

The second phase repeats the second with more learning: the yellow brick. And a touch more testing.

With phase three we are up and running: support for activities, which can be as inventive as the course creators want and the technology and budget permits. Content is delivered in a variety of ways and testing continues in a style and manner that by now, if not a little later, will be formal, requiring an 80% pass rate.

Phase five, which segues into a phase six of sorts, is crunch time: formal assessment with a tough, longer quiz that has built on previous ones and a peer reviewed written assignment too. These need to be constructed with extraordinary skill and care given that students will be marking each other’s work, and where many, if not most, will not have English as their first language. As well as testing there should be a chance here to gather one’s thoughts, to reflect and even go over some of the learning in the course.This might also be the time for those who have become friends during the course to pick up the conversation on Facebook or in a LinkedIn group. It may also be the moment when you buy ‘the book’ on which the course was based, or sign up for the next module in the series.

In future posts I will use this approach to ‘strip down’ and re-assemble a number of MOOCs. For example, ‘Learning How to Learn’ from Coursera written and presented by Barb Oakley. I should also look on MOOCs I have done on Search Engine Optimisation (SEO), on Photography and a variety of other subjects.

Education is becoming a branch of medicine

Still reflecting on two days of intensive listening, discussing and brainstorming the future of education at the Coursera Partners’ Conference at The Hague, The Netherlands I conclude that education is becoming a branch of medicine: there is a science to education through neuroscience and psychology. Digital learning, which draws a mass attendance and participation through ‘Massive Open Online Courses‘ can be analysed, duplicated, shared, repeated, improved and gradually made universal. Might ‘fixing math’ or even reading across millions be akin to a Polio vaccination? Ways are being found to educate ‘on mass’ and to deliver to millions a common level of achievement.

Coursera, and organisations like it, are educating the world: anyone, any time, any where.

Only access is getting in the way: a broadband link or opportunity to stream or download content, take part in discussions and submit assignments; money to purchase the gadget – increasingly as smartphone over a tablet or laptop; time away from the daily task of staying alive: fetching water, gathering and preparing food, raising a family, working and completing chores; cultural objection to some receiving an education … freedom from oppression in the home, community and the politics of the region or country. Otherwise ‘the world’ can join in; hundreds of thousands take part in MOOCs. Coursera has over 18 million learners. FutureLearn, starting a year later, is catching up with 3 million. Coursera thinks of itself as a movement; some of its educators, such as Barb Oakley, are becoming its prophets. She has a readership, a following and fans.

There are early and late adopters: those who jump at innovation and others who shy away from it.

A study of ‘The Diffusion of Innovations‘ would be of value.

Why do some academics embrace learning online, the opportunity of sharing knowledge, ideas and thinking with hundreds of thousands rather than a handful of students at a time? Are they the ones who stuck with the horse and carriage when the motorcar came along? Are they the ones who use a fountain pen on lined paper rather than a wordpressor? Should be picture them as medieval knights with armoured helmets designed not to protect the head from blows from outside, but to keep the contents of their brain contained? Will they join the party?

What are the barriers to MOOCS from the most traditional educational establishments and their educational practices?

Can, for example, the ‘Oxbridge Tutorial’ be taught online?

I put this question to a gathering of Coursera staff and Coursera Partners at the 5th Coursera Partners’ Conference. The question I posed became the focus of the brainstorming session: in groups we scribbled as many reasons for resistance on Post Its which were duly adhered to a conference room wall, pondered over, grouped and categorised. Looking at some of the reasons it was felt that some institutions, faculties and individual academics simply feared the new and its disruptive force:

Learning Online, or ‘e-learning‘ despite its universal presence on campus through networks and WiFi is a practice or behaviour that may appear interesting in theory, and is used vicariously by all in practice where content and research online blurs the boundary between library and online resources, but it ‘isn’t for them’; they ‘don’t do online’ – something they say with sorrow in their eyes, not unlike when people say they ‘don’t do Facebook’ or ‘don’t have a TV’ – some people prefer to avoid change, or leave it to others. Is it an age thing? Are younger academics more in tune with the new ways?

The connectedness of social media dilutes the tutor-student relationship. A student may have their feet on campus, but their head ‘in the cloud’. Why shouldn’t they take a free online course from another institution while they attend lectures, seminars and tutorials at yours. Already they will draw papers and publications onto their laptop from digitised libraries rather than needing to wait in line to call something up from the stacks.

I fear that some educational institutions, those with a history of 750 years to hold them back, will suffer the way EMI has in the music industry. Perhaps one day neither academics, nor the students who follow them, will need these institutions. They’ll become museums; after all, they are already a tourist honeypot. Colleges at best will reinvent themselves and through the likes of AirBnB rooms will be let out on a rolling basis to a vast, shifting body of students at different stages of their education pass through all year around. Instead of the annual crush to fill examination halls, these rooms too will be used the year round as no other close scrutiny of student learning than the written examination can be found or relied upon.

Knowing academics, more so in research than teaching, they can operate in silos and cliques.

They cherish the privacy of their study and doing everything alone. The problem for them with this new way of learning is the feeling that only they could instigate and produce what they see as an exchange of knowledge that needs to pass from their heads to those of their select few students. Not having worked ‘in the real world’ of collaborative corporate teams they don’t understand the need for partners and facilitators to get their content into a consumable online, digital form. Perhaps they don’t know how easy it can be. Perhaps, it wouldn’t be surprising, they are perfectionists. They look at what is online and find it flawed or trivial. Often they don’t understand it. They know their subject, but beyond the paper, lecture or tutorial they haven’t used a mutable, interactive, connected, mass medium of knowledge transfer such as the MOOC. At best they confess that it is ‘not for them’ but invite you to talk to their younger colleagues. Or the American in the faculty. Where lies the answer: they should and could turn to their colleagues, the PhD students and undergraduates.

The idea that bureaucracy gets in the way is not unusual for any institution or organisation facing change. No matter the size some organisations find change easier than others. There has often been good reason why in the past change has taken time. Better to get it right and take a few years over it, that rush in early and get it wrong. There have been casualties in the race to put educational content online. A blended learning environment of sorts exists whether institutions and academics want it or not; students will communicate and share online, important collections, papers and books have been digitised. It may be a tough call to expect an outsider to instigate change. Some educational establishments are like the Vatican, a walled city of ceremony, hierarchy and procedure.

If we think of Oxford, my alma mater was Balliol College, and Cambridge by default, the examples of ‘traditional’ institutions that on a global scale hold top ranking faculties across many subjects still are these collegiate, federal institutions encumbered by the buildings from which they operate? Colleges, quads, studies and staircases, common rooms and dining halls, libraries and chapel? Are they encumbered by the times they keep: short, intense terms with a pattern that sees written examinations taken annually? Or does the digital ocean wash through them regardless? It is ironic that the Oxford Internet Institution, founded in 2001 encourages and even embraces multi-disciplinary, cross-faculty collaboration and learning, yet there are no MOOCs of its own that it can study. Education has become part of the science of the Web. Or can Oxford bide its time? Watch others succeed or fail then in good time leap frog the early adopters? It has the resources: the manpower and financial backing. Why then did Harvard not produce its own learning platform?

Some learning online gives it a bad name. In time institutions such as Oxford will have the evidence to make up their minds. What works and what does not. What will find a fit with Oxford, and what will not. Academics will work with learning designers and programmers, they will have analysts picking through performance and results, stars will be born and great minds discovered.

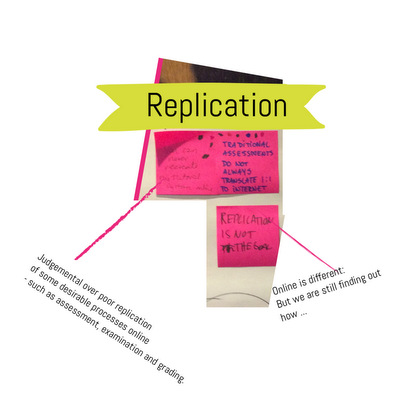

In the context of this brainstorming sessions ‘replication’ came to mean the transferability or otherwise of current education practices to the online environment. In particular the discussions was around assessment and grading. Institutions have different models and practices of course, with attendance mattering to many, and course work the way, whilst at Oxford and Cambridge the end of year and final exams remain the focus of academic effort and probity. Replication of what we do offline and putting it online doesn’t always work. Our ‘desktop’ on our computers does not have to look like a desk – though for a while in the 1990s some did. Some tests can be conducted online and identity proved. It isn’t so hard, The Open University has found, to identify someone who has been a student of theirs. Coursera, in the various courses, quizzes and assessments I have submitted want a screengrab of your face – cheats could overcome this for now, but the level of ID match, as passport control services in international airports are showing, can be hugely improved. Recreating the ‘Oxford Tutorial‘ will be the subject of another post. While the intimacy of a tutor to student one to one each week is hard to scale up to cater for hundreds of thousands at a time, there are qualities to forums and online discussions that are akin to this. FutureLearn has found a way to manage threaded discussions that run into a thousand posts or more: you can pick out a handful of commentators to follow, and therefore create your own bespoke ‘study group’ for example. A senior academic may ‘drop by’ in person, though more likely PhD and MA students will take part for the learning benefits to them to have a surrogate teaching and support role.

LearningOnline2016CorporateRelationships

Time is money. Intimacy is costly. The tutorial system, where a senior academic for several hours a week sits with a small group of undergraduates, say two or three at most, requires time, space and place. Often these tutorials are one to one. The student isn’t charged £100 or £200 an hour, but if a figure were to be put on it, accounts might want to add an hour. They may not be lawyers, but the advice and support they give to an individual student could be charged in six minute increments. How do you scale it up? Artificial Intelligence? If anyone could or will do it, might a virtual Stephen Hawking one day take multiple physics tutorials where you the student interact with an avatar?

It all comes down to money.

For most of the seven centuries of its existence the students resident in Balliol College where there through privilege: they had the time and money to indulge a higher education. For a few decades it was free. In England a grant took you through your first degree, and if you wanted to take a second you often could. This indulgence, in England at least, is over. Oxbridge, like other universities in England (it differs in Wales and Scotland) can charge £9,000 per academic year – a fraction of the real cost, and nothing like the $45,000 a year in might cost for a student in the US. In much of ‘continental’ Europe higher education is still state, or department funded.

There is understandable resistance to put online and in theory give away for free, what others are paying for – whether that is the individual, or the government or region through grants or subsidised loans.

However, where we are citing Oxford and Cambridge, compared to many educational establishments they are both wealthy and able to call for donations from wealthy individuals and organisations. Cost should not be a barrier to an Oxbridge MOOC. Though, looking at MOOCs from Harvard, one has to wonder if money, and the perception it brings in production values, is off putting? If you ask 200,000 wannabe engineering students from around the world if they’d like to study at Oxford, Harvard or Cambridge how many might say ‘no’ ? It is interesting that the MOOC ‘Learning How To Learn’ by Barb Oakley of the University of Michigan, ‘shot’ in her basement and produced for around $5,000 could have more students enroll than ALL Harvard’s MOOCs combined. With simplicity and authenticity comes psychological accessibility. Barb Oakley is approachable, perhaps these ‘elite’ institutions are not? It has taken Oxford, for example, nearly 40 years to address the gender imbalance and imbalance of ‘private’ to ‘state’ educated students. For too many, the perception of the ‘dreaming spires’ of Oxford is one of exclusion, academic snobbery and inaccessibility.

So does it all come down to ‘the brand’. Ironica that in a discussion on concerns that elite educational institutions have over change that such a modern, marketing term should be used. If Oxford can be brand savvy, then surely it is savvy enough about all other corproate practices and can, or is embracing change? But will it, or a faculty, or a professor with one strand be the first on the Coursera platform? Or will they use Edx or FutureLearn? Will they mix it up … or will they, or are they, creating their very own, exclusive, platform for ‘massive, open online courses’?

Finally, when is a MOOC not a MOOC?

For all this talk on the MOOC as some kind of immutable way forward for learning, while the ‘masssive’ cannot be denied with hundreds of thousands enrolling and tens of thousands completing such courses, how do you define ‘open’ when parts of MOOCs being closed to those who can pay a few to be assessed, or pay a fee for access to certain parts of a course? And is it ‘online’ if it can be downloaded? As soon as you have it on your device it is potentially as unconnected to the outside world as a book.

We are all learning how to learn online.

Undoing the blogging habit of a decade

For a decade I’ve settled into a blog post every morning.

For the last couple of weeks I’ve at least been forming a new habit. Whether 3.30am or 5.40am I get up and work on fiction ’til breakfast. That out of the way I can get on with the rest of the day. This leads to early nights. But am I missing much? ‘I’m a celebrity get me out of here?’ No thanks.

A first from The OU – a TMA that was an audio file that came back with written comments and an audio file.

A very different beast learning a language. Both in the text and the spoken word there is lots to pick up on.

Facts in an essays are like pepper in soup – the wonders of FutureLearn, the Paris Conference of 1919 and the birth of the League of Nations

|

| From E-Learning V |

Fig.1. Facts in an essays are like pepper in soup

How do you compare and mark a variety of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs)?

We need to treat them like one of those challenges they do on Top Gear, where Jeremy Clarkson – Richard Hammond – James May set off to Lapland in a Reliant Robin or some such and then get marks across six or so criteria. Hardly scientific, but it splits the pack.

So, let’s say we take THREE MOOCs, what criteria should there be?

- Commitment. What percentage of participants signing up complete the course?

- Comments. I use the word ‘vibrancy’ to judge the amount and nature of activity in the MOOC, so this is crudely reduced to the number of comments left.

- Likes. Another form of vibrancy where comments left by the team and by participants are ‘liked’. It has to be a measure of participation, engagement and even enjoyment

- Correct answers. Assuming, without any means to verify this, that participants don’t cheat, when tested are they getting the answers right. This is tricky as there ought to be a before and after test. Tricky to as how one is tested should relate directly to how one is taught. However, few MOOCs if any are designed as rote learning.

You could still end up, potentially, comparing a leaflet with an Encyclopaedia. Or as the Senior Tutor on something I have been on, a rhinoceros with a giraffe.

It helps to know your audience and play to a niche.

It helps to concentrate on the quality of content too, rather than more obviously pushing your faculty and university. Enthusiasm, desire to impart and share knowledge, wit, intelligence … And followers with many points of view, ideally from around the globe I’ve found as this will ‘keep the kettle bowling’. There is never a quiet moment, is there?

I did badly on a quiz in a FutureLearn Free Online Course (FOC). World War 1. Paris 1919. A new world order …

I think I got half right. I chose not to cheat, not to go back or to do a Google search; what’s the point in that. I haven’t taken notes. I wanted to get a handle on how much is going in … or not. Actually, in this context, the quiz isn’t surely a test of what has been learnt, but a bit of fun. Learning facts and dates is, or used to be, what you did in formal education at 15 or 16. This course is about issues and ideas. A ‘test’ therefore, would be to respond to an essay title. And the only way to grade that, which I’ve seen successfully achieved in MOOCs, is for us lot to mark each others’ work. Just thinking out loud. In this instance the course team, understandably could not, nor did they try, to respond to some 7,000 comments. They could never read, assess, grade and give feedback to a thousand 4,000 word essays. Unless, as I have experienced, you pay a fee. I did a MOOC with Oxford Brookes and paid a fee, achieved a distinction and have a certificate on ‘First Steps in Teaching in Higher Education’.

As facts are like pins that secure larger chunks of knowledge I ought to study such a FutureLearn FOC with a notepad; just a few notes on salient facts would help so that’s what I’ll do next week and see how I get on. Not slavishly. I’ll use a pack of old envelopes or some such. For facts to stick, rather than ideas to develop, the platform would have needed to have had a lot of repetition built into it. Facts in an essays are like pepper in soup.

Armed with an entire module on research techniques for studying e-learning – H809: Practice-based research in educational technology – I ought to be able to go about this in a more academic, and less flippant fashion.

How to take notes for effective studying and assessment

Fig.1. The muddy sides of the River Ouse, Piddinghoe. At low tide.

We are very good at forgetting: it’s vital.

We see, feel, sense far too much in our daily lives (which includes when asleep). Come to think of it what on earth was I doing on a student exchange to North America last night where I am twenty years older than my hosts … (probably sums up how I feel about the workplace).

See. Some memories are made for us, or by us whether or not we want them.

Learning though requires us to gather, create and retain stuff. Some of this stuff is forgettable; it doesn’t resonate, or is poorly taught or expressed. Or we simply don’t get it the way it is expressed, or the first time around.

Make it a memory

At an OU Residential School the session on revision was packed. The tips made us laugh: sucking a choice of Polo Fruit sweets by subject theme – when you come to the exam repeat and each sweet will link you to that period of revision. Odd. But it worked often enough for me to convince me of its value.

Fig.4. Ebbinghaus and his ‘Forgetting Curve’

The science from the likes of Hermann Ebbinghaus and his ‘Forgetting Curve’ simply indicates how something fades, unless you go back to it a few times over several days over which period you make it stick. It doesn’t say anything about the ‘stickiness’ of the memory in the first place. Sometimes this stickiness is made for you. There is drama, there is an explosion. Most likely, by chance, the learning is anchored by some unrelated event like the fire alarm going off – that won’t work for 50 different things though.

Fig. 5 Multiple ways of making ‘it’ stick: read (book and e-book), highlight, tag and take notes.

If the module, or your tutor isn’t doing it for you then the next step is to dig around for a book, video or image that does it for you.

Most likely, and of far greater value, is for you to turn that lesson into a memory of your own creation. There is always value in taking notes, so never listen to the presenter who says ‘no need to take notes I’ll give you the slides afterwards’. Never trust the quality of the slides. What the person said will be of more value then the slides. You, and your handwriting, and your doodles are how it starts to become a memory. Then when you write up or rewrite those notes you do it again. You make it into something.

Fig.6 The River Ouse at low tide.

I’m fixating on the horror of drowning in a shell-hole in the First World War.

Ever since I was a boy those images of cowboys and Arabian princes sinking into quicksand has horrified me. What must it have been like? Walking the dog by the River Ouse at low tide just as it turned the gurgling of water backing up and filtering into the muddy bank gave me the shivers. That sound was ominous. It made a memory of the walk and the thought. It’s also what is sustaining me as I work at a short story.

Fig. 7 A family memory of a wedding in California. Will it stick?

We’ve talked about ‘memory making’ in the family.

It is the event, and the sharing of the event. My late mother-in-law was horrified that her daughter couldn’t remember a road-trip they did across the US when she was 13. I concluded that she hadn’t remembered much, or couldn’t remember much when it was mentioned out of the blue, as the trip was never shared. Conversations are and were always about current and future events. This is why it helps to get the old photo albums out from time to time. But there’s a loss. Do we make them anymore? Visiting a mislabelled album online is never the same.

Fig. 8. My late grandfather John Arthur Wilson MM with the author Lyn Macdonald at the spot north of Poelcappelle, Belgium where he buried two of his mates – 75 years after the event. He recalled it ‘like yesterday’.

Recalling the First World War

Some veterans would talk, others remained silent. Those who did not want to remember could and did forget. My late grandfather was a talker; it drove my mother mad. I came to love his recollections. Clearly, there were events that would have burned themselves into the memories of these men, but unless they talked about it, in a veteran’s association or with family and friends it was not going to stick. No wonder veterans would seek each other out over the decades. Nudged by histories and movies their memories could be changed though; sometimes they came to say what was expected of them ‘the rats were huge, the generals useless, the German bunkers impenetrable, the mud up to your waist, the sound of the individual shells … ‘

In conclusion

Whatever activities and devices are built into your module, you are responsible and can only be responsible for making something of it. Take the hint. Engagement takes time so make the time for it. These days it is made easier through the Internet. You can keep a blog to share or as a learning journal; you can talk it over with fellow students either asynchronously in a forum (or blog), or synchronously in a webinar. You can ‘mash it up’ with images, grabs, doodles and annotations. You can make it your own. It’ll stick if you want it to but superglue requires effort. Someone else ‘sticks it’ for you and it won’t happen.

Essay writing style: clay or concrete aggregate?

| From River Ouse Low Tide |

My tried and tested methodology, beyond the doomed ‘winging it’ is ‘concrete aggregate’. Other weeks or months I accumulate a lot of stuff, much of it in a blog like this; not quite a relational database but the ‘stuff’ is here, tagged and of reasonable relevance. In a now defunct OU ePortfolio called ‘MyStuff’ or ‘MyOU’ – I forget, you could then shuffle and rank your gobbets of nonsense and so, discounting the volume of stuff, potentially, have a treatment that could then be turned into an essay.

Such stuff, if it contains, 10,000 words, often with chunks of verbatim passages, can be a hell of a task to hack into shape. You build in bold forms out of concrete and can only get it to look like a garden, or park sculpture, with a pneumatic drill and chisel. Sometimes it works. You get there. It is dry and workable. You’ll more than pass. It depends on the subject, the module and the specific expectations of the assignment. Where you need to tick many boxes this approach may work well.

Clay is the better way forward in most situations. Here you build up your arguments in logical steps then refine them at the end. This, particularly in the social sciences, is where the tutor wants to see how you argue you case, drawing together arguments and facts, mostly those you’ve been exposed to in the module, though allowing for some reading beyond the module. You have to express your opinion, rather than listing the views of others. Get it right and this is the only way to reach the upper grades? Get it wrong, which is the risk, and you may end up with a hollow or limp structure with grades to match.

We remember thanks to repetition

|

| From E-Learning III |

Repetition or re-visiting is vital. We cannot help but change our perspective as we gain more experience, insights and knowledge. We need repetition in order to get ‘stuff’ into the deeper recesses of our brains where wonders are worked. Therefore, far better to exposure to brilliance often, rather than giving them something less than brilliant simply because it is new, or an alternative. If nothing else Web 2.0 ought to be giving students the chance to find and limit themselves to the best.

University Of California Approves Major Open Access Policy To Make Research Free

Over 125 million people want a university education – current global provision struggles to cater for 5 milllion – making the source content free doesn’t create an educational package – it lack the scaffolding, assessment and accreditation, but it is food for the hungry.