Home » E-Learning » Mobile learning

Category Archives: Mobile learning

Is an App on WW1 better than an eBook and better than a book?

Dan Snow. “Clearly an App is better than a book for history.”

This is a fascinating insight into the way we learn and educate is changing with students exploring, creating and sharing from an App ‘smôrgasbord’ of rich, interactive content.

I picked up this thread in the WW1 Buffs Facebook pages

This conversation will keep me busy for several months. The debate on the guardian site is heated, personal and too often Luddite in tone. Why try to say that a book is better than an eBook is better than an App that is ‘book-like?’ I’ll be pitching in as I believe what he argues is right and applies immediately to Geography too. I‘ve studied online learning, history and geography – all to Masters level. I’m not an historian, geographer or an educator: I’m simply deeply curious and fascinated by the way we learn.

Key to Apps is immediacy, relevancy and motivation.

Put content into a student’s hands in a way they appreciate: at their fingertips, multi-sensory and connected. An App can take all that is a book, and add several books and angles; all that is TV or Radio and have the person sit up, create content of their own, form views, share opinions and therefore learn, develop and remember.

Proud and happy to call myself a ‘Master of Arts’

|

| From E-Learning V |

Fig.1. Mr Kung Fu – was he the master or the pupil?

When I completed enough modules early last year to graduate as a ‘Master of Arts: Open and Distance Education’ I felt like a fraud; I’d scraped through, more importantly I didn’t feel I was ‘fluent’ enough in the subject. One module, H817 had been replaced and had felt a little dated at the time. This is why I’ve ended up doing a couple more MA modules from the MAODE – I have only one missing from the full set (H817 Open) which I may do in due course. I could even put it towards an M.Ed (Masters degree in Education) for which I also need the compulsory 60 point module Educational Enquiry which next registers a year from now.

| From E-Learning V |

Fig.2 The forgetting curve

Confidence to call myself a ‘Master’ and belief by others that I know my subject led me to being asked to join the Open University advisory panel on the MAODE and in the same week to join the board of advisors for a national educational body that recently met. Now I feel I have enough of ‘the knowledge’ at my fingertips. I prepared for this first meeting my searching through this blog: it shouldn’t surprise me to know how much I’d forgotten, studying why and how we forget is very much a part of education – it is summed up in the Forgetting Curve (fig.2) that Hermann Ebbinghaus thought up over a hundred years ago.

|

| From E-Learning V |

It intrigues me that no gadget we own can circumvent this: that in fact, take a SatNav for example, let’s assume that it takes you on a journey in the correct direction. Let’s say you keep using the SatNav regardless. You could probably turn it off after two or three of these trips as your brain lays down the landmarks in your longterm memory. Thinking of which, I think the SatNav makes an excellent model for e-learning; just image you need to learn 120 absolute facts as a junior doctor – you could have your SatNav ‘peg’ the facts to specific points of a familiar journey. When you sit the exam it’s then as easy as driving this route in your mind’s eye visualisation everyone of the facts along the way.

I wander, cloud like.

I’m writing up my notes from this national advisory panel and over the next four years can hopefully nod at the courses that appear on which I’ve had some influence. Still not there yet, but I’m one heck of a long way further on since February 2010 when I re-booted this malarkey.

The answer has to be a P.hD. And I guess the only place to do that would be with the Open University. I went off the boil on that one a year ago, though I did secure a couple of interviews but came away suitably crushed.

It will have taken by then, at least ten years, more like 12 or 13, to call myself a ‘Digital Scholar’.

Just a distraction?

Fig.1. Tom Dailey winning Commonwealth Gold

Tom Dailey talks about his bid for a medal the the Rio Olympics, about distractions like school and TV work, and also his desire to do a course, such as Spanish.

“Because I’m not doing any school any more and I haven’t got any TV shows, possibly I want to start a course in Spanish, sociology, politics, something like that, just to keep my mind away from it.

“If your mind is constantly on diving, it will melt. It’s always good to have a distraction from it.”

It sounds like he should be introduced to the Open University; there were a few Olympic competitors on courses a few years ago. What could be more flexible?

Is it a distraction? Is studying complementary to the day job or daily life?

Any other competitive athletes out there?

I’m still with the OU for a couple of reasons:

- 1) I love learning and the OU method and platform

- 2) Anything to keep me away from the TV is a good thing

- 3) In the case of French I’ve always wanted to, and at one stage needed to crack written French.

What do we know about learner-types by studying museum visitors ?

Fig.1. From the paper LISTEN: augmented audio-augmented museum guide (c) Andreas Zimmermann, Andreas Lorenz (2008)

This is a paper presentation at a conference of a museum visitor guide system that uses a combination of tracking/observation and audio-artifacts to create a personalized visitor experience. The paper reveals the extent of trials, tests and adjusts as well as evaluation which in turn offer ways that a proposal might be in the form of a presentation of the platform or a workshop that might assess how visitors are profile at the start of their visit.

Fig.2 One of the many multimedia moments at the ‘In Flanders Fields’ museum, Ypres. C. 2013 In Flanders Fields

I had in mind some kind of open, mobile personalized learning for use by visitors to military museums, perhaps national trust properties and even battlefields.

Each of these offer very differ user experiences and expectations though. A literary research reveals that the planning for visitors to an exhibition, collection of curated events or gallery is complex and the history of using technology to support visitor experiences is lengthy.

The research for conference papers is approached from two directions: the standard approach through the OU online library using terms such as ‘museum’ ‘elearning’ and ‘augmented’, while also drawing on personal knowledge of the many digital agencies based on the South Coast (profiles of these companies are available from the regional hi-tech association ‘Wired Sussex’).

Cogapp have been producing digital content for museums since the mid 1980s.

These and other agencies often present ‘papers’ at conferences, though the quality, in academic terms, of these presentations is sometimes questionable – is it promotion or is this the presentation of valid research?

Fig. 3 On Alcatraz. Following my audio guide, but too enthralled to be on site amongst a hubbub of people.

I can also draw upon a personal interest in museums, galleries, and other visitor attractions from national trust properties to battlefields all, or some of which, come with some kind of ‘guide’ – traditionally as a leaflet or guide book (Picasso Museum, Jean Miro), often with an audio guide (Alcatraz, Muir Woods, Royal Academy: Van Gogh, Bronzes), though increasingly from online resources with some attempts to use modern mobile devices (Design Museum, Tate Modern) or to personalize the experience (In Flanders Fields, Ypres). (Great North Museum)

There are major, global conferences on e-learning, some with an orientation towards, or significant presence from the museum sector. Over the last decade there has been considerable interest in improving, through personalization, the visitor experience.

The attraction of this paper, although it is limited to an audio platform whereas I had in mind something visual, the narrative from conception to testing, delivery and evaluation is thorough. It is insightful on studies of the museum visitor experience, curator relationships with artifacts, use and potential of audio and tracking/observation technology – both hardware and software (Zimmermann and Lorenz, 2008:391)

-

motion-tracked wireless headphones

-

current position

-

head orientation

-

individualized and location-aware soundscape

as well as content preparation and feedback on an iterative process.

These approaches will become increasingly sophisticated, discrete and effective for different visitor ‘types’, even reflecting how a person’s behaviour may change during the course of a visit. It is insightful to discover the degree of sophistication for understanding perception types (Zimmermann and Lorenz, 2008:391)

-

self-perception

-

visual

-

tactile space-perception

-

acoustic space-perception

And visitor types:

A definition of personalized (Zimmerman and Lorenz, 2008:394)

-

Adapts

-

Layers of information

-

Increasing levels of involvement

Pedagogical (Zimmermann and Lorenz, 2008:400)

-

increasing knowledge

-

increasing comprehension

-

considering the social context

McCarthy and McCarthy 2005 distinguish four types of learners:

-

imaginative

-

analytical

-

common sense

-

experimental

Gardner 1993 identifies seven:

-

linguistic

-

logical-mathematical

-

musical

-

bodily-kinesthetic

-

spatial

-

interpersonal

-

intrapersonal

Veron and Levasseur 1983 determined visiting styles based on observations of animals (Zimmermann and Lorenz, 2008:404):

-

ants (following the curator’s path)

-

fish (holistic point of view)

-

butterfly (interest in all exhibits without following the curator’s path)

-

grasshopper (interest only in specific exhibits)

leading to the Macke Laboratory outputs of:

-

sauntering: the visitor is slowly walking around with an excursive gaze.

-

goal-drive: the visitor displays a direct movement with the gaze directed towards a specific artwork.

-

standing, focussed: the visitor is standing with the gaze directed towards a specific artwork

-

standing, unfocused: the visitor is standing or sitting with an excursive gaze

(Zimmermann and Lorenz, 2008:409):

- fact-orientated – putting a high eight on spoken text

- emotional – prioritizing music pieces and sound effects

- overview – focusing mainly in short sound entities

REFERENCES

Arnone, M, Small, R, Chauncey, S, & McKenna, H 2011, ‘Curiosity, interest and engagement in technology-pervasive learning environments: a new research agenda’, Educational Technology Research & Development, 59, 2, pp. 181-198, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Boehner, K, Gay, G, & Larkin, C 2005, ‘Drawing evaluation into design for mobile computing: a case study of the Renwick Gallery’s Hand Held Education Project’, International Journal On Digital Libraries, 5, 3, pp. 219-230, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Bohnert, F, Zukerman, I, Berkovsky, S, Baldwin, T, & Sonenberg, L 2008, ‘Using interest and transition models to predict visitor locations in museums’, AI Communications, 21, 2/3, pp. 195-202, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Brugnoli, M, Morabito, F, Bo, G, & Murelli, E 2006, ”Augmented itineraries’: Mobile services differentiating what museum has to offer’, Psychology Journal, 4, 3, pp. 311-335, PsycINFO, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Cocciolo, A, & Rabina, D 2013, ‘Does place affect user engagement and understanding?Mobile learner perceptions on the streets of New York’, Journal Of Documentation, 69, 1, pp. 98-120, Library, Information Science & Technology Abstracts, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Edwards, C 2013, ‘BETTER THAN REALITY?’, Engineering & Technology (17509637), 8, 4, pp. 28-31, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Forsyth E. AR U FEELING APPY? AUGMENTED REALITY, APPS AND MOBILE ACCESS TO LOCAL STUDIES INFORMATION. Aplis [serial online]. September 2011;24(3):125-132. Available from: Academic Search Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 5, 2013.

Gaved, M, Collins, T, Mulholland, P, Kerawalla, L, Jones, A, Scanlon, E, Littleton, K, Blake, C, Petrou, M, Clough, G, & Twiner, A 2010, ‘Using netbooks to support mobile learners’ investigations across activities and places’, Open Learning, 25, 3, pp. 187-200, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Jarrier, E, & Bourgeon-Renault, D 2012, ‘Impact of Mediation Devices on the Museum Visit Experience and on Visitors’ Behavioural Intentions’, International Journal Of Arts Management, 15, 1, pp. 18-29, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Marchetti, E, & Valente, A 2012, ‘Diachronic Perspective and Interaction: New Directions for Innovation in Historical Museums’, International Journal Of Technology, Knowledge & Society, 8, 6, pp. 131-143, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Mengmeng, L, Hiroaki, O, Bin, H, Noriko, U, & Kousuke, M 2013, ‘Context-aware and Personalization Method in Ubiquitous Learning Log System’, Journal Of Educational Technology & Society, 16, 3, pp. 362-373, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

McAndrew, P, Taylor, J, & Clow, D 2010, ‘Facing the challenge in evaluating technology use in mobile environments’, Open Learning, 25, 3, pp. 233-249, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Semper, R, & Spasojevic, M 2002, ‘The Electronic Guidebook: Using Portable Devices and a Wireless Web-Based Network to Extend the Museum Experience’, ERIC, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

STOICA, A, & AVOURIS, N 2010, ‘AN ARCHITECTURE TO SUPPORT PERSONALIZED INTERACTION ACROSS MULTIPLE DIGITALLY AUGMENTED SPACES’, International Journal On Artificial Intelligence Tools, 19, 2, pp. 137-158, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

Zaharias P, Michael D, Chrysanthou Y. Learning through Multi-touch Interfaces in Museum Exhibits: An Empirical Investigation. Journal Of Educational Technology & Society [serial online]. July 2013;16(3):374-384. Available from: Academic Search Complete, Ipswich, MA. Accessed November 5, 2013.

Zimmermann, A, & Lorenz, A 2008, ‘LISTEN: a user-adaptive audio-augmented museum guide’, User Modeling & User-Adapted Interaction, 18, 5, pp. 389-416, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 5 November 2013.

LINKS:

Recommended: MIT’s sixth sense device. Do you know about it? Here’s a link to it: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ig2RSID-kn8&feature=youtube_gdata_player

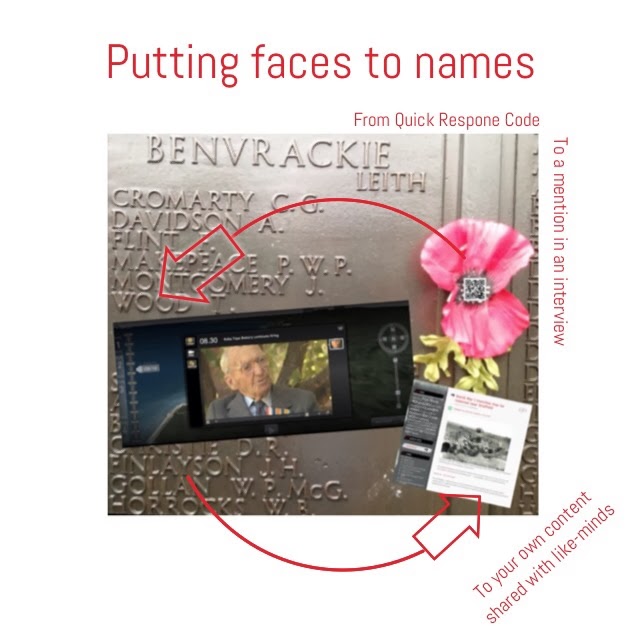

How to use Quick Response Codes in teaching about the First World War

Leveraging mobile technologies and Web 2.0 tools to engage those with an interest in the centenary of the First World War in the stories of the people of the era using strategically placed Quick Response codes.

Open Education in an Open Landscape

Inclusion: Innovation: Implementation

An OULive presentation by Jonathan Vernon 17th February 2014 @20:45

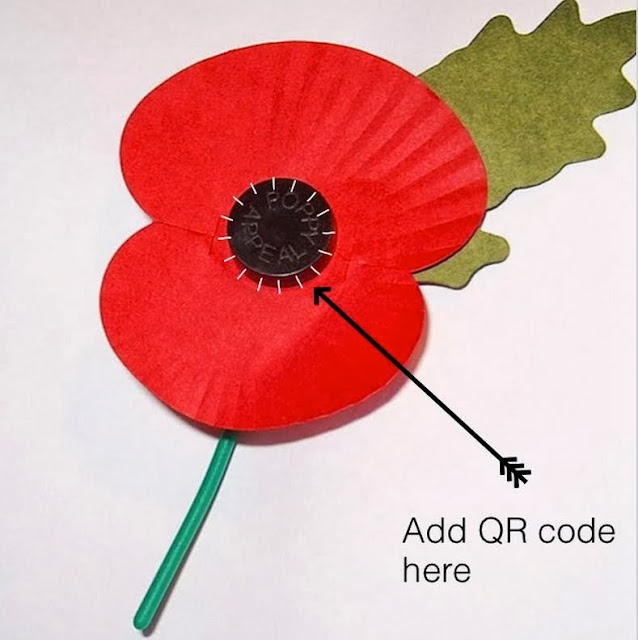

I’d like people to add a Quick Response code to their Commemoration Poppy

Fig. 1. Mashup of a Royal British Legion Poppy with a Quick Response code that links to the story of a veteran of the First World War.

Who are them men and women whose lives are remembered on British War Memorials?

Fig. 2 First World War War Memorials in Lewes and Brigthon

The problem with war memorials is that those named on them risk becoming forgotten words on a list. By using the Web we can find out who these people were and where they lived: we can try to put a face to the name and a story to the name – and then we can share what we find online.

There are more than 54,000 war memorials in Great Britain, most of these put up after the First World War; there is barely a community without one. There are some 900,000 names. Significant interest already exists, especially as we approach the centenary of the First World War making this initiative a potentially easy one to add, to what is already taking place.

“Fast, cheap and out of control”

Brian Lamb (2010) described those technologies that ‘lend themselves to … the networked and open approach’ (Weller, 2012 KL 244) as ‘fast, cheap and out of control’. It was with this in mind, taking an interest in the centenary of the First World, that I started to think about using Quick Response codes as a personalized entry point to the Web that anyone could generate in order to share a story about someone who served in the conflict, and to do so both online and on the street.

Fig. 3 How a Quick Response code might be used on a Royal British Legion Poppy in order to personalise your commemoration.

Quick Response (QR) codes are fast – they are easy to use, they are free; however to be effective in learning there has to be a ‘ modicum of control’ – the initiative has to come from somewhere. Worn in this way, I’d like to think that you can share directly with others the person whose name you have researched and whose life you wish to remember, as well as directing people to the content online and inviting them to ‘adopt’ a name from a war memorial themselves. This is designed as a ‘blended experience’, that uses ‘face-to-face’, ‘community’ and ‘classroom’ experiences, trips to monuments … and qualities of being and going online.

Fig. 4 QR codes are a product of the car manufacturing industry

Faced with increasingly complex components, Denso, a supplier to Toyota, came up with what is a 2d barcode in the 1990s. (Denso, 2014) Made free of patent, and using free software anyone can now generate their own unique QR code; you can even print them out on standardized sticky label stationery. There are a myriad of uses for QR codes, from embedding information that is read and stored by the device to a quick link to rich content online. The interest here is to use QR codes to link to learning resources, in mobile, or ‘m-learning’ contexts in particular, and for users to both ‘read and write’ such content. I liken QR codes to using your phone as a remote control to click to a TV channel. You point a smartphone, or tablet at the QR code to read it and go instantly, pretty much, to a web page. Unlike a TV remote though, you can just as easily create and share your own content too.

The use of QR codes in education in the last decade has been limited

Refereed papers are few, but between these and other published reports, suggestions can be made regarding their strengths and weaknesses. If QR codes are to be used successfully then champions need to be identified to take up the cause. Whilst QR codes use the power of the Web to connect people to rich content, that they may create themselves, a good deal of thoughtful planning will be necessary, not just explaining how to make use of QR codes, but also working them in, where appropriate to current learning schedules where QR codes can contribute to meeting clear learning objectives.

The 2009 Horizon report identified six technologies that were expected to be significant in the following few years, of these, five relate to this proposed innovative approach to learning by wearing a personalised QR code:

-

mobile devices,

-

cloud computing,

-

geo-positioning

-

the personal web and

-

smart objects.

Use of QR codes in learning has had mixed results

Simply putting a QR code in front of a museum artifact, as they’ve done at the Museum of London and did at the Design Museum does not work (Vernon, 2013) – there isn’t enough to attract or necessitate their use, not everyone has a smartphone or tablet, and the technology is often not robust. While outdoors QR codes added to signs in the South Downs National Park, (Kerry-Bedel 2011) for example, barely received a view a day during a three month trial and in some instances there was no signal anyway.

Where QR codes have been successful is in targeted learning experiences in schools (Gradel & Edson, 2012), where the affordances of the QR code have been exploited to form part of an engaging, constructive and collective learning experience.

To be effective this initiative with war memorials requires galvanizing people to take part in a joint exercise – easier with a class in school or college, less easy with the general public.

Examples where QR codes work include:

-

where participants are ‘equipped’,

-

where they can take an active role, such as with ‘on the spot’ surveys or quizzes,

-

where they are prompted into cooperative learning

-

and where timely ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ are given.

(Awano, 2007: Information Standards Committee 2008; So 2008; Robinson, 2010; Hicks & Sinkinson, 2011; Ryerson Library & Archives, 2012.)

K Lepi (2012) Copyright 2013 © Edudemic

Fig 5. A Simple Guide to Four Complex Learning Theories. Lepi (2012)

The theory behind the idea of using QR codes in a mobile and open way, is that in the digital age ‘connectivism’ is the modus operandi. In Fig. 3, an infographic produced by Edudemic (Edudemic 2012) traditional and digital theories are shown. All are relevant, each has its place, with the digital environment offering new approaches to learning.

Learning ‘in the digital age’ enables and benefits from a level and quality of interaction and connectedness that is easier to achieve on the Web. It is particularly effective where the body of learners is large, where ‘birds of a feather, flock together’ (Li & Chignells, 2010) at a hub (Efimova, 2009) and their behaviour is open and shared so that knowledge acquisition comes through the challenges and rewards of sustained interaction. (ibid)

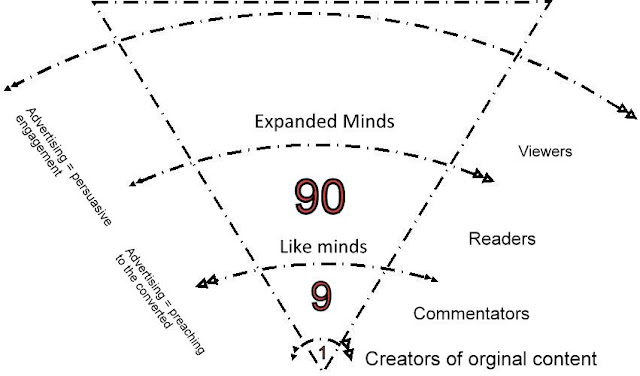

Only a fraction of an online population are naturally inclined to generate content. Nielsen (1999) suggested that only 1% create content, 9% might comment, while the remainder are readers or viewers. Nielsen cites the Amazon book reviewer who wrote 1,275 reviews in one year. I liken these people to what advertisers call ‘champions.’ The key influencers of a cohort or group, early adopters, who innovate first and do so with conviction and passion. (Vernon, 2012).

Fig. 6. Creators, commentators and readers – how use of the Web stacks up. Vernon (2010) after Nielsen (1999)

So if we are to rely on participants to generate content the total numbers taking an interest as viewers and commentators needs to be large. Building on Nielsen, and authors who have called groups who identify with each other through connected blogs as ‘like minds’ and my own experience in advertising I devised Fig. 4 to suggest degrees of participation.

How I would see it work with War Memorials is that as well as the key creators, there would also need to be, say branch members of an organisation such as the Western Front Association, they have over 3,000 members with branches across the UK, as a body of ‘like minds’ supported to work on the content, a figure increased further by engaging local schools or colleges – especially where the work is made part of formal assessment.

A balance has to be found, I believe, between the qualities of a tool that is ‘fast’ and ‘cheap’, and where, if it is ‘out of control’ – but you want to use it, to do so by creating parameters or ‘scaffolding’.

Fig. 7. Following ‘City Walks’ near Bloomsbury Square, London.

The potential weaknesses of using QR codes include the requirement for participants to have a suitable device, say a smartphone or tablet and communication fees. QR codes may not be so easy to stick to, then read from, a standard Poppy either. Reading from and using a smartphone or tablet presents accessibility issues. Though these devices are also being used in resourceful ways to support people with disabilities, and an audio guide, say a minute per name, for a war memorial, has its appeal.

Fig. 8. A mash-up of old photographs overlaying a Google Map

In relation to creating and sharing content in an open culture, Robert Capps (2009) coined the expression ‘the good enough revolution’. This precludes being prescriptive or from expecting perfection. Whilst output on the First World War from the BBC and the Open University should understandably attain a certain professional standard, the kind of creation required of those researching names on war memorials themselves should take inspiration from this ‘good enough revolution’. Examples include ‘pinning’ names from a war memorial to a home address, sharing photographs in a Flickr gallery, ‘pinning’ World War One photographs to battlefield maps, sharing photographs on Pinterest, numerous inventive YouTube videos, shared documentaries and memoirs presented as blogs.

Fig. 9. A mash-up of War Memorial which featured a Poppy, adding a QR code and links to an interactive online activity and a blog.

What has been shown, in museums and ‘out in the field’, is that simply ‘put out there’ QR codes are ignored. This makes the idea of ‘wearing your Poppy featuring your QR code’ appealing, as each person becomes an ambassador on the ground, in the street, on site, for that nugget of information, especially so if they are also responsible for – and proud of creating the content you then link to. The opportunity exists to engage people in bringing the stories of those named on our war memorials alive and sharing this knowledge in an invigorating, dynamic and Web 2.0 way. As a result, a deeper and more meaningful connection is made with the past and our relationship to it.

REFERENCE

Awano, Y (2007). Brief pictorial description of new mobile technologies used in cultural institutions in Japan. The Journal of Museum Education, 32(1), 17-25

Capps, R (2009) ‘The GOod Enough Revolution: When Cheap and Simple is Just Fine’, Wired Magazine: 17.09. Avaialble at http://www.wired.com/gadgets/miscellaneous/magazine/17-09/ff_goodenough?currentPage=1 [accessed 18th February 2014]

Denso (2014). QR Code Standardization. Available at http://denso.com/ [accessed 18th February, 2014] also at http://www.denso.com.au/Products/Non-Automotive/Data-Capture/QR-Code

Edudemic. Traditional Learning Theories. Available at http://edudemic.com/2012/12/a-simple-guide-to-4-complex-learning-theories/ [Accessed 19th April 2014]

Efimova, L. (2009) Passion at work: blogging practices of knowledge workers. Novay PhD

Research Series 2009. Available at www.novay.nl.dissertations [Accessed 19th April 2014]

Gradel, K., & Edson, A. J. (2012). Higher ed QR code resource guide.

Hicks, A., & Sinkinson, C. (2011). Situated questions and answers: Responding to library users with QR codes. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 51(1), 60–69.

Information Standards Committee (2008) Section 3: QR code, Synthesis Journal. (From http://www.itsc.org.sg/pdf/synthesis08/Three_QR_Code.pdf )

Kerry-Bedel, A (2011) Smartphone technology – the future of heritage interpretation: Its in conservation. Avialable at http://www.kbstconsulting.co.uk/QR/images/ITIC.pdf [Accessed 14th February 2014]

Lamb, B (2010) ‘Open Contempt’. Available at http://wiki.ubc.ca/Open_Contempt [accessed 18th February 2014]

Li, J., & Chignell, M. (2010) Birds of a Feather: How personality influences blog writing and reading. Science Direct. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 68 (2010) 589-602

Nielsen, J (1999) Web Usability

Robinson, K. (2010). Mobile phones and libraries: Experimenting with the technology. ALISS Quarterly, 5(3), 21–22

Ryerson University Library & Archives (2012). QR codes. Retrieved 6th Feb 2014, from http://www.ryerson.ca/library/qr/.

So, S. (2008). A Study on the Acceptance of Mobile Phones for Teaching and Learning with a group of Pre-service teachers in Hong Kong. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 1(1), 81-92.

Vernon, J.F. (2012) How Blogging is going all TV. (Blog post) Available at http://mymindbursts.com/2012/01/06/how-blogging-is-going-all-tv/ [Accessed 18th February 2014]

Vernon, J.F. (2013) Mobile learning at the Museum of London: QR codes and NFCs. (Blog post) Available at http://mymindbursts.com/2013/11/10/molqr1/ [Accessed 14th February 2014]

Weller, M (2011) The Digital Scholar: How Technology is Transforming Scholarly Practice. 5% Loc 239 of 4873

Repetition or re-visiting is vital.

|

| From E-Learning III |

Repetition or re-visiting is vital.

We cannot help but change our perspective as we gain more experience, insights and knowledge. We need repetition in order to get ‘stuff’ into the deeper recesses of our brains where wonders are worked. Therefore, far better to exposure to brilliance often, rather than giving them something less than brilliant simply because it is new, or an alternative. If nothing else Web 2.0 ought to be giving students the chance to find and limit themselves to the best.

The use and better use of QR codes in learning

Fig.1. Here a ‘Near Field Code’ offers the visitor further information as a rich ‘nugget’ delivered to their smart phone – though not to iPhones. My perfect guide would have been my mother at my side.

An avid visitor to museums, galleries, historic houses and battlefields I have become intrigued by the kinds of guidance offered and the way this has changed with the greater use of IT and in some instances the use of Quick Response or Near Field codes. All of them appear to try to recreate the perfect visitor support – the sympathetic, well informed guide at your shoulder explaining what’s what and tailoring their response to your interests and level of interest. I had this, and my children, nephews and nieces got it too from my late mother on visits to art galleries. An artist who had studied art history too, she had a way of picking out nuggets of information and insight about an artist and their trade.

Fig. 2. Some galleries and museums now offer an audio guide that is at least triggered by your proximity to an exhibit.

Though you are of course still beholden to the words and tone of the expert, even if their words are spoken by a broadcaster. From time to time the quality of the content stands out – in my experience the audio-guide for visitors to Alcatraz in the Bay of San Francisco stands out because it had to my ears the hallmarks of a BBC radio docu-drama – expertly written and crafted with the right mix of interview clips from former inmates, and prison guards.

As learning experience this is still one way – however memorable I am neither constructing my own narrative nor sharing much with others, until of course you take off your headphones and share your feelings and thoughts with other family members.

A QR code offers more than just a switch that triggers a nugget of reading, viewing or listening at a specific spot – it offers the chance to take people to content that you provide and to make connections that lead to conversations and discussion. It is these aspects of the QR code that are of interest to me, students as ‘produsers’ and participants, having responsibility for, even pride in, content that they research, put online, tag and then promote with a QR code and then return to as the curator and moderator of their content, sharing and expanding their views through ‘connected learning’ practice.

Fig. 3. Using Quick Response codes to bring those who served in the First World War to life

In relation to the First World War, to achieve this requires more than simply sticking QR codes to poppies, and leaving poppies at memorials, in the railings outside historic buildings, or in the ground on battlefields – it requires three kinds of champion: institutional support, educator support and these ‘produsers’ – a term coined by the Australian academic John Bruns when writing about the value of blogging.

The institution, by way of example, in the UK, might be the British Legion, Imperial War Museum, Western Front Association or National Trust – as well as smaller, regional and local associations. The ‘educator’ to use its broadest sense is the classroom teacher or university lecturer who once introduced to QR codes sees how their use can be exploited within their own learning programmes.

Fig.4. My visualization and conception of those who are most active at generating content. After Jakob Nielsen (1999)

While the ‘produser’ is that rare 1% in an online population, like those who generate content for wikipedia, keep a blog or post video content to YouTube, who can be encouraged, within the context of the First World War to use QR codes in imaginative and innovative ways, probably drawing viewers to content or adapted content, that they have already created and in doing so indicating to others how straightforward it can be to upload a photograph and some text, or if they are moved to do so, to write a poem, compose a song, paint a picture, make a sculpture, complete some research or tell a story – and then to share it, especially at times and in places that are most appropriate.

REFERENCE

Bruns, A. (2005) ‘Anyone can edit’: understanding the produser. Retrieved from http;//snurb.info/index. php?q=node/s86

Nielsen, J (1999) Web Usability

Book or eBook? A case of apples vs. oranges or analogue vs. digital?

Fig. 1. Learning in the digital age. J F Vernon (2013)

You’re missing a trick if you’re ignoring eBooks.

My experience studying at postgraduate level over the last four years, first with the Open University and now with the University of Birmingham as well is that we need to consider and experience the affordances of both.

Fig. 2. EBook vs. the Book. It’s largely down to context – do you read on the go, or in a library? Have you got shelf space?

I will own the book and the eBook in some circumstances as they offer a different experience and options.

If you are studying a subject in a social context online it helps to be able to share what you find and think as you read. I did this with Martin Weller’s book ‘The Digital Scholar’ and found he was reading along through Twitter and my blog. I find where I have the printed book that I take photos of pages, mash these up and then share online – or resort to pen, paper and note taking in the traditional, lonely way. Then there are the huge tomes, some of the history books I am getting through right now that run to 900 pages – it is so much easier to carry around on the iPad. Using an eBook I highlight by themes of my choosing, add notes, Tweet short passages, seek out threads on single characters, link directly to references and post mash-ups from screen-grabs rather than photos straight into a e-portfolio so that the idea or issues are tagged and ready for later use.

Non-fiction books will become like some LPs of the past – do you want all the tracks or just your choice?

If I can buy 12 chapters of a book for £8.99 on Kindle, when will I be able to buy for 99p that one chapter I need? Speaking to a senior engineer from Amazon over the summer (old friends who moved to Silicon Valley twenty years ago) he wondered if the ‘transformative’ period for books was about to occur, just as it has occurred with music.

There will be a better, personalised hybrid form in due course, several of which I have tried. So far they have been marred by only one thing – poor content, the clickable, multimedia, well linked experience is apt for the 21st century.

Fig. 3. Mash-up from Martin Weller’s book ‘The Digital Scholar’ using the App ‘Studio’ to add text and icons to a cropped grab of a page.

Nothing replaces scholarship though , it’s just going to take a while to make the transition.

Add a QR Code here

I would like everyone to adopt a veteran from the First World War – whether their name is featured on a memorial or not, whether they survived or not. Participants create any kind of online commemoration (blog would be easy, or video, or podcast, or slide show) – likely to be of a distant family member (great grandfather, great uncle, great great aunt) or someone from a person’s immediate community (lived in their house – spooky). A community of interested people may then build around a specific town/village, railway station of post office memorial, for example. Schools may find the stories of and pictures of combatants.