Home » E-Learning » Research

Category Archives: Research

Why most published research findings are false

Why most published research findings are false

REFERENCE

Ioannidis, J A 2005, ‘Why Most Published Research Findings Are False’, Plos Medicine, 2, 8, pp. 696-701, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 12 February 2013.

The contents of my brian

Fig. 1. A moment to reflect

This by the by was the title of a TV screenplay I submitted to the BBC – rejected otherwise you might have seen it on the box by now and I wouldn’t be sitting here.

As the round up to my final, final MA ODE module H818: The Networked Practitioner it is suggested that we prepare a timeline drawing on possible blog entries, as well as ‘appearances’ in the OpenStudio platform we’ve been using.

I’ve posted some 80 times since H818 began. I’ve posted some, I don’t know, 1000 times here since February 2010?

The surprise is to find a dozen references to H818 from 2012 and when contemplating how I got to the ideas that I delivered for H818 where these may have emerged from. This in turn takes me as far back as a visit to the Science Museum in 2010. Then all manner of things, from the launch of Martin Weller’s book ‘The Digital Scholar’ and attending seminars in Bristol on ‘curation’ and earliest indicators that I may take an MA in First World War studies having tried to write on the subject for … well, 22 years ago another failed TV play optioned by Tyne Tees Television called ‘That’s Nothing Compared to Passchendaele’ – which is what my late grandfather said to me while we watched the local news featuring a private in the Durham Light Infantry out in Saudi Arabia. He was 96 in 1992 and had joined the DLI in his teens in late 1915.

And all of this for my very, very, very last EMA ever.

And what did I just jot down

‘Word counts in an EMA are anathema to the culture of open education’

My first draft, I haven’t ever dared look, will run to anything between 6,000 and 12,000 words.

Talking of writing … never one to say never, I have committed to a week long ‘retreat’ with a dear friend and writing tutor. My goal is to work on … ‘The Angel of the North’ a story set in the era of the First World War about a woman who flies over the Western Front.

(Actually, I’ve just thought of that. She does fly with an RFC pilot/instructor … and in the final pages is about to set off to attempt to fly the Atlantic for the first time in the wrong direction. She does, as a couple of women did, impersonate a soldier to get herself into the Front Line …)

Oh boy. And I thought I was done with writing. Thought that getting 5,000 words finished was a challenge. It is, but the OU provides the parameters and schedules, the kick up the arse and the carrot that no other kind of writing has yet provided. Except for once.

Meanwhile I must get the kids to school, must walk the dog and must prepare for an online conference I madly volunteered to do a few weeks ago as if I didn’t have enough on … which will include sitting with a veteran of the Second World War this weekend, he was in the Polish Resistance during the Warsaw Uprising. I have a Sony Flip camera and digital sound recorder in my pocket determined to interview him as I did my grandfather …

Onwards to … more of the same I should think

p.s. yes, it is my ‘brian’ – the idea of the brain is so ridiculous.

eBooks vs. textbooks – towards the hybrid

It amazes me how when reading something and pointed to a footnote or reference that if I choose to do so a few clicks and the reference is before my eyes. Reading up on the First World War there are books from 1914-18 that are freely available in digital form – the additional insight is when you glance at such a reference is to wonder why an author chose that sentence or paragraph, often I find there is something far more interesting being said.

All of this has me reflecting on ‘interpretation’ and how increasingly, because we can, we should, because we can, check up on authors – certainly take them off their academic pedestals as their word is never absolute, is inevitably biased – and sometimes they get it wrong.

There are two kinds of connectedness here:

1) with references the author has used – how selected, why they thought them of relevance or interest (and the authority and credibility of these references)

2) with fellow readers – which, if you want a response, I increasingly find in Amazon of all places. There are always a few people who have picked through the text, who are willing and able to other a response or to sleuth it out with you.

How does this change things?

The Web puts at anyone’s fingertips resources that until recently were the exclusive domain of university libraries – the older, wealthier universities having the richest pickings and broadest range of references. To ‘look something up’ as we now do in a few moments could take a couple of days. ‘Learning at the speed of need’ is a phrase I like, used in the context of applied learning in business, but just as apt here.

As a consequence, earlier in their careers, students will have a broader and stronger, personal perspective. And as a consequence there will be more people ‘out there’ to join an informed discussion. And as a consequence more new ideas will come to fruition sooner and faster. And as a consequence, collectively, or common understanding will grow and develop faster than before.

Can an email-prompted web-based e-learning platform aimed at undergraduates in the UK with moderate to persistent asthma improve compliance to their prescribed preventer drugs to 80%?

Fig. 1 Preventer, Reliever and volumetric. With good adherence the ‘brown one’ is taken as prescribed and the ‘blue one’ rarely needed. With poor adherence there is no brown on and there is dependence on the blue one. In this example a QVAR easibreather and a Venotlin inhaler. Mine.

By presenting these ideas here I asking for support on how to make this research happen.

The medical profession is replacing the term ‘adherence’ with the term ‘compliance’. This reflects the desire to encourage self-management of prescribed drugs in concordance with health care providers (HCPs). For the purposes of this paper the terms should be considered interchangeable.

Asthma is a chronic and complex condition affecting the lungs that can be managed but not cured. (NHS Choices, 2013) (See Appendix 1 for a definition of ‘moderate to persistent asthma’). The World Health Organisation estimates that 300 million people globally are asthmatic (Web, 2001) while in the UK in 2010 5.4 million people were receiving treatment for asthma and there were 1,143 deaths. (Asthma, UK. 2013) An estimated 75% of hospital admissions for asthma are avoidable and as many as 90% of the deaths are preventable. (Asthma, UK. 2013) 80% compliance is the minimal level required for treatment to be effective (Lasmar et al., 2009).

Research construct

Asthmatics form a heterogeneous group that shows great diversity of triggers, effective medication, management strategies and outcomes. Research clusters asthmatics into four to six groups based on how they present and the drug regime they are on (Webb, 2011). Isolating a participant’s conditions and being confident that their medication is correct will be a challenge. For this reason, thorough in-depth interviews with participants, potentially with an HCP present, will be vital in order to set a benchmark.

A team at Harvard Medical School designed Qstream, the proposed e-learning platform (Kerfoot et al., 2008). Qstream (Fig.1.) takes its approach from an understanding of Ebbinghaus (Ebbinghaus, 1913) and how we forget and remember to provide a spaced-learning response that uses a combination of email alerts and interactive content to build knowledge. Its use has been researched with junior doctors in relation to their formal medical training and assessment (Kerfoot et al., 2008; Kerfoot et al., 2012) and in applied settings with healthcare practitioners to support informed decision-making. (Kerfoot et al., 2010)

Fig.1. Screengrab from Qstream homepage. (www.qstream.com)

On the basis of their research, Dr B Price Kerfoot says that ‘educational games work’ (Kerfoot et al., 2008. Kerfoot suggests that the next step is to use this approach with patients and ‘clinical decisions of greater complexity’ Kerfoot (2010:477). Research using Qstream involving people with chronic illnesses is planned to take place in North America in the Fall of 2013 (Vernon and Kerfoot, 2013).

What is the problem?

Too many people with a chronic illness, such as asthma, fail to take their medication as prescribed (Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) of Great Britain, 1997; Hayes et al., 1979). This can lead to an exacerbation of the disease, risks hospitalization and even death. Non-compliancy rates are between 10-60% (Cochrane, 1992. Rand,1994), 30–50% (Horne, 1999), 50% (Di Matteo, Giordani, Lepper & Croghan, 2001; Kyngas, 2007 in Wales et al., 2011:148).

Reasons for non-compliance include medication side effects, expense of treatment, personal value judgments or religious or cultural beliefs about the proposed treatment, age–related debility, not having an action plan prescribed by an HCP, the patient not following the adequate treatment prescribed (Cerveri et al., (1999:288) or the presence of a mental disorder (e.g., schizophrenia, personality disorder). American Psychiatric Association [DSM-5], (2013:726).

What is the opportunity?

According to McGavock et al., (1996) efforts to improve compliance have been unsuccessful; it is hoped that efforts using e-learning will be successful. The healthcare community – manufacturers, prescribers and frontline carers, recognise that education offers a way to reduce hospital admissions and deaths (Cerveri et al.,1999:288). The opportunity exists to increase compliance to 80% and therefore improve the health of millions of people with asthma.

A variety of programmes have tested a potential solution to non-adherence. (Byer & Myers, 2000; Hand, 1998; Tettersell, 1993), while Hacihasanoğlu and Goözuöm (2011) showed that patient education on medication adherence is effective. A variety of studies on e-learning in healthcare have used emails linked to multiple-choice questions and answers to improve patients’ knowledge and behaviours (Volpp et al. 2009; Kato et al. 2008).

The hypothesis

The hypothesis is that as a result of greater compliance through a ‘spaced learning’ e-learning education programme, non-compliant moderately persistent asthmatics will show changes in measurements of their illness and changes in their medication beliefs. (Based on Petrie et al., 2012:76).

Desired outcomes / results

Having completed a programme of e-learning using Qstream people with moderate to persistent asthma who had been noncompliant (under 80% compliant) should show changes in their illness and medication beliefs, improved compliance to their preventer inhaler and measured improvement across a range of physiological measures. (Based on Petrie et al., 2012:76) As a result of what they learn, the research will address patient perceptions, such as beliefs (Horne & Weinman, 2002), worries about long term use of steroids (Apter et al., 2003), fears and other concerns (Kaptein, Klok, Moss-Morrs & Brand, 2010). For example, 28% of asthma patients think that drugs are bad and not necessary while 12% think that drugs may not be not bad but aren’t necessary. Cerveri et al., (1999:292).

Achieving a reasonable level of compliance with treatment regimes has been shown to improve the health outcomes of patients undergoing treatment and reduce demands on health resources (Bender, Milgrom, Wamboldt & Rand, 2000; Dunbar-Jacob, Burke & Puczynski, 1995).

The long-term and broader opportunity exists to reduce hospitalizations, reduce costs, improve and extend lives.

Learning Theories

The learning theories that form the basis of Qstream are behaviourist (Skinner, 1974) and cognitive (Wenger, 1987; Hutchins, 1993; Anderson, 1983; Piaget, 1952) with problem solving, explanations and re-combinations. In line with this behaviourist approach early versions of Qstream worked best in formal learning contexts, for example first year medical students needing to pass an exam on anatomy. (Kerfoot et al., 2008) and practical clinical guidelines (Kerfoot et al., 2009). By complementing traditional medical training, with clear goals and the motivation to pass, the attraction of the platform are clear in this context. This stimulus-response approach, builds on the work of Ebbinghaus (1913) (Fig. 2)

Fig. 2. A typical forgetting curve for newly learned information. After Ebbinghaus (1913)

Through association, the learner takes a number of steps to build a composite skill. (Skinner, 1984; Gagné, 1985) (Fig.3) An accurate reproduction of knowledge can be assessed or demonstrated in drill and practice.

Fig.3. Screengrab from Qstream showing how a participant receives feedback on their response to a multiple-choice question.

Later and current versions of Qstream include components of peer competition, participant interaction and collaboration. This constructivist approach takes the view that learners build their own structures (Piaget, 1954). It also suites task orientated learning (Bruner, 1993) and assimilative learning. This constructed and socio-constructed approach to learning is less suited to assessment simply by looking at exam grades, therefore in-depth interviews or comprehensive self-reporting surveys are required to elicit what took place and the level of knowledge attained especially as evidence of learning by people with asthma won’t be elicited through formal assessment.

Why undergraduates?

The research shows that younger asthma patients in the age 14-25 years are less likely to use their preventer medication than older patients (Diette et al., 1999; Legorreta et al., 1998), which makes ‘young people an important group to target for improving adherence and reducing their underuse of preventer-inhaler corticosteroids’, (Pertie et al., 2012:75). For this reason, and to exploit study parameters of population size and geography, a university undergraduate population is proposed.

METHODOLOGY/METHODS

A mixed-method approach will be adopted with qualitative and quantitative components. In-depth pre and post intervention interviews will form the qualitative element, while the quantitative component will be based on several hundred student participants taking part in a randomized controlled trial and use analytics generated by the Qstream platform. The aim is to interview approximately 30 students in-depth within the parameters of a single university. For example, Adams, Pill & Jones, (1997) favoured in depth interviews with a carefully selected and eligible number of patients before and after intervention. For quantitative analysis the far larger pool of participants will be drawn from a UK wide undergraduate student population using platforms such as The Student Room (www.thestudentroom.com. The Student Room, 2013) and Asthma UK to recruit participants. According to Kerfoot & Baker (2012) an individual randomized control trial is preferable were there is a large sample size. Extending to a sample of four UK universities might increase the potential number of participants to 9000+ (See Appendix 2). Self-reporting screening would be used to ensure that only those in the desired group took part.

Based on UK statistics on asthma in the population, it can be calculated that at, for example, the University of Southampton from a total undergraduate population of 17,000 there are likely to be between 485 and 586 students with moderate to severe asthma. (This intentionally excludes those likely to have a mild form of the disease, and those with a profoundly severe form of the condition). (See Appendix 2 for break down of likely respondents). Asthma UK (2013) suggests that amongst asthmatics 48% consider themselves to be at risk. If this percentage of potential participants volunteered then the starting population for the proposed research is likely to be around 250. It is reasonable to suggest that by working with four different universities of a similar size the total population for a randomized control trial would increase to 1,000.

Identifying those who are moderate to severe asthmatics and agreeing criteria has confounded asthma studies in the past, therefore great care will be required to set parameters, the simplest being that where an asthmatic has been prescribed only two medications, a preventer inhaler (known as the ‘brown one’) and the reliever inhaler (the ‘blue one’) that their condition is considered to be ‘moderate to severe’.

Having a sound basis for giving a person’s baseline, for both compliance and knowledge of asthma and how it is treated, will indicate if an improvement in adherence has been made and whether this e-learning approach has been effective.

To have a physical measure you can audit the prescriptions issued or weigh the inhalers to establish how much has been expelled, however Spector (1985) found cases of both miss-application and trial firing. A blood test is definitive, but this could only be carried out by an HCP. The alternative is to ask patients how they got on, however patients are thought to overestimate their actual drug use by between 30 and 50% (Spector, 1985; Sacket and Snow, 1979). In the case of people with asthma, Horn (1992:126) found that 11% who claimed to have inhaled salbutamol in the preceding four hours had no detectable drug in their urine.

Whilst therefore there are advantages in conducting interviews, patients are giving a subjective measure of their treatment compliance (Sawyer, Rosier and Phelan, 1995). This method suffers from being the most inaccurate of any available (Horn, 1999:126), however the alternative requires a series of tests that need to be administered by an HCP.

This ethnographic investigation would be open and exploratory (RPS, 1997). A system of meanings would be taken either from transcripts (Scherman and Löwhagen, 2004:4) or preferably from audio recordings as current best practice in medical market research favours working from the audio as nuances of meaning are more likely to be apparent (Kazmer & Xie, 2008).

Given the complexity of influencing compliance and the desire to use this as a measure of effective learning, structured and semi-structured in depth interviews will take place. In addition physiological improvements to lung functionality need to be measured for a sample of the participants to offer an objective indicator that a change of behaviour has occurred.

Other influences on outcomes that should be revealed in a semi-structured interview include issues of identity in relation to learning (Kirkup, 2001; and Hughes, 2007) and motivation, what Resnik (2008) describes as ‘passion based learning’.

The text from these interviews will be analysed for clusters of meaning, aiming to pick out nuanced responses, potentially from video but at least from audio recording of interviews (Kazmer & Xie, 2008), which according to Webb (2011) is preferable to working from text alone

The aim would be to reveal the experiences of those interviewed and so come to a view of ‘understandings and misunderstandings’ about their condition, the role their prescribed ‘preventer’ medication plays and the value of Qstream.

Qstream offers a variety of ways to monitor and measure activity on the platform (fig. 4) . This is how data and metadata from several hundred participants would be analysed. (Appendix 3 lists the affordances of using a Qstream private site)

Fig. 4. Screengrab showing example of analytics available on a group of 356 learners.

TIME LINE CHART

Fig. 5. Simplified model of research. Punch (2006: KL 487 )

Eligibility for interviews and physiological testing would be based on patients with the indicated symptoms though excluding patients with serious social problems and severe learning difficulties. (Franklin et al., 2006)

Aim to recruit 30+ students for in-depth interviews and <1000 for a randomized controlled trial using the Qstream platform. Confirm participants, ensure that they understand the terms and nature of the research and request that they read and agree to these and that participation is voluntary, information will be confidential and their written consent is required. Invite all or some to complete either an asthma Journal or, as they have been shown to be effective, an audio log. Patient-reported outcomes would help us understand the impact of drugs on patients’ lives and activities. “Are patients really doing better? Can they sleep through the night rather than waking up with a sense of shortness of breath?” Bohen (2013: 863)

Pre-Qstream Interviews

Run Qstream e-learning programme for 12 weeks

Post-Qstream Interviews

Analyse data and metadata generated by the Qstream platform

Write up and report findings. Follow up a year later to see if the impact of the learning is maintained over time through changing behaviours. |

Limitations

No study of a therapeutic regime can be considered fully valid without some documentation of whether the patients took their treatment. Horn (1992:127) Establishing valid data on whether people take their medication as prescribed will be a challenge.

No single method of assessment of compliance with (anti-asthma) therapy is ideal nor does any one method give a full picture of the pattern of compliance. Usually the chosen method(s) will require to be validated specifically for the particular circumstances under investigation.

An issue arises with using an Internet and mobile alert system where potentially limited or broken Internet access or paid-for Wi-Fi impinges on the student’s access to the resources. Care will be taken both over how content is scripted and produced, as well as securing a robust platform. Kerfoot and Baker (2012:13) had problems in relation to: ‘server errors’, ‘attrition’ (Kerfoot & Baker, 2012:4), ‘fatigue’ (Kerfoot et al., 2010) and technical hitches due to spam blockers (Shaw et al., 2011) as well as the challenging nature of the content. (In Vernon, 2013)

It is also reasonable to suggest that those who are noncompliant to regularly taking their prescribed medicine could also be ‘noncompliant’ to the features of Qstream – a twice or thrice weekly prompt to take a few minutes to answer some questions.

A UK license for up to 1,000 participants to use the Qstream platform is $15,000 per annum.

In research carried out by ZoRA et al. (1989). Only 1 in 17 diary sheets completed by asthmatic children (under age 14) were accurate to within 10% of the number of puffs used. Whilst the participants in this research are older, any completion of a dairy sheet will include errors and inaccuracies.

Overestimation in self-reporting is well known and probably due to a desire to please. (Cochrane, 1995. Cochrane 1998)

Failure of a therapeutic regime can only be ascribed to poor compliance if appropriate drugs are being prescribed in adequate dosage that historically has tended not to be the situation in the management of asthma. (Horn, 1992:127)

The population using the Internet is diverse. This impacts on research in relation to access and having a representative group of participants. (Eynon, 2009). The use of Qstream in a student population favours use of a mobile device for ease of response to email prompts. It is suggested that 53.7% of people in the UK will be using smartphones by 2014 with those aged 18-25 by far the largest group followed by teenagers (New Media Trend Watch, 2013) whilst it is estimated that nearly 38% will have tablets by this time. (eMarketer, 2013).

Ethics

For ethical reasons an institutional review board would be approached for approval to perform this study. (Kerfoot & Baker, 2012:2) (In Vernon, 2013)

-

A standardized form will be used to obtain informed consent from participants.

-

Well Being, confidentiality and anonymity will be stressed.

-

Rights will be clearly explained

-

The personal safety of those conducting the research will be considered.

-

Conflicts of Interest will be declared, for example, Dr Kerfoot is on the board of Qstream.

-

Unintended consequences will be considered.

-

People have to have the freedom to make mistakes in relation how they elect to adhere, or not, to the prescription drugs they are prescribed. Mental Healthcare Act.

Validity and reliability

If one hope is to correlate a physiological change with improved knowledge an array of factors need to be isolated and measured. Data from both a qualitative and a quantitative approach, the clusters of issues and ideas from analysing what is said in pre and post interviews and the activity on the Qstream platform will offer some indication of what is taking place and why.

Implications for future policies, practice and further research

1) Socio-constructed learning and connectivism

It is further hypothesized that effective compliance is most likely to be achieved where in addition to the patient, the related HCPs engage in the proposed e-learning programme. Social interaction has an important role to play in learning. (Vygotsky, 1978) Donath (2002) shows how through exchanging information a person gains recognition and that social learning of this kind provides affiliation. This suggests value in having HCPs, even family, especially parents and guardians, of younger people with asthma taking part in a Qstream learning programme and exploiting how we connect in networks (Kit Yee et al., 2011) Wang (2008:05) considers the importance in learning of both the student and instructor. HCPs would play the role of ‘intermediaries’ (Laurillard, 1993).

This not only invokes ideas of values relating to communities of practice (Lave and Wenger, 1991) but also, in our digital age, to ‘connectivism’ (Siemens, 2006; Calvani, 2009: de Waard, 2011) – where ‘nodes of readily available information’ are linked to and shared between learners. (Edudemic, 2013) The asthmatic as a learner can question their own knowledge and understanding by connecting with others, as part of a ‘community of practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991), from the periphery (Brown, 2002; Brown, 2007) and vicariously (Cox, 2006). Connecting with other people with asthmatics online is supported by the Asthma UK website (Asthma UK, 2013)

2) Use of narrative and creative content

Fig. 5 Screengrab introducing a series of animated videos on design. Open Learn (2013)

The quality and style of scriptwriting using the Qstream platform will impact on effectiveness. (Laurillard, 2000 and Jewell and Hooper, 2011) understand the role of narrative in learning. Resnik and Chang (2008) talk about the need for e-learning to be self-revealing, pleasurable and fun, with a ‘low threshold and high ceiling, supporting collaboration, plugins and making it iterative’ and ‘tinkerable’. The Open University, through Open Learn, often use rich video content to engage audiences, for example with a series of short video in ‘Design in a nutshell’. (Open Learn, 2013)

3) Further personalisation of e-learning

Intelligent Web pages that can adapt themselves to a person’s linguistic and other competence are examples of more ambitious applications that we might look forward to in coming decades. (Hara et al., 2006:352)

4) Extend duration of study period

This study would initially be restricted to a single term or academic year, though it could be extended, for example, to include first year undergraduates through the 3 to 4 year duration of their undergraduate studies. Ostojic et al., (2005) carried out a 4-month trial, whilst trials run by Kerfoot (2008-2012) have run for as long as 45 weeks.

5) Include other chronic illnesses:

Allergic rhinitis is comorbid with asthma (Bousquet at al., 2013) warranting its inclusion in future research alongside studies on asthma. Other chronic illnesses that may benefit from Qstream’s use by patients includes diabetes, epilepsy, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

6) Consider ‘Big Data’, Web 2.0, Pedagogy 2.0

There is the potential of automatic real-time data gathering relating to inhaler use with a microchip and the use of wearable technology even an ingestible smart pill (Engineer Online 2012; Arnold, 2013) in medicine. Supported by enhanced patient knowledge of their illness. Armed with this data, analysed automatically, and read by the patient or an HCP, the drug regimen and response to it is closely monitored. Such patient analytics are akin to student performance analytics (Koller, 2012) providing HCPS and educators with the potential for gathering and analysing data and metadata from hundreds of thousands of participants.

Conclusion

The opportunity exists to develop an e-learning programme that change lives – that improves the health of those with moderate to persistent asthma. Research suggests that greater knowledge and understanding of a chronic medical condition and personal medical and lifestyle responses and self-management improves compliance. However, the way the illness presents are complex, the triggers and symptoms vary greatly. The approach suggested here also offers the chance to establish if learning brings about a change in behaviour that can be measured in a physiological response – improved lung function and the role an e-learning platform can play. In due course, if a reasonable percentage of the 300+ million asthmatics who are online engage with an e-learning programme such as this significant insights and improvements to health can be made.

REFERENCES

Adams, S., Pill, R., Jones, A. (1997) Medication, chronic illness and identity: the perspective of people with asthma. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45:189-201

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Revised 5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Arnold, M (2013), ‘A VIEW TO A PILL. (cover story)’, Medical Marketing & Media, 48, 6, pp. 26-30, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, viewed 26 June 2013.

Asthma UK (2013) Asthma facts and FAQs. http://www.asthma.org.uk/asthma-facts-and-statistics (Accessed 23rd June 2013)

Bohen, S (2010) Sean Bohen, senior vice president of early development at Genentech (in Smith, B 2010. The Future of Pharma)

Bousquet, J, Khaltaev, N, Cruz, A, Denburg, J, Fokkens, W, Togias, A, Zuberbier, T, Baena-Cagnani, C, Canonica, G, Van Weel, C, Agache, I, Aït-Khaled, N, Bachert, C, Blaiss, M, Bonini, S, Boulet, L, Bousquet, P, Camargos, P, Carlsen, K, & Chen, Y 2008, ‘Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA) 2008 Update (in collaboration with the World Health Organization, GA2LEN’, Allergy, 63, pp. 8-160, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, (Accessed 19 June 2013).

Brown, J.S. (2002) The Social Life of Information

Brown, J.S. (2007) October 2007 webcast:http://stadium.open.ac.uk/stadia/preview.php?whichevent=1063&s=31

Calvani, A. (2009). Connectivism: new paradigm or fascinating pot-pourri?. Journal of E-learning and Knowledge Society, 4(1).

Cerveri, I ; Locatelli, F ; Zoia, MC ; Corsico, A ; Accordini , S ; de Marco, R. (1999) International variations in asthma treatment compliance – The results of the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL Volume: 14 Issue: 2 Pages: 288-294 DOI: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14b09.x Published: AUG 1999 (Accessed 21st June 2013)

Cox, R. (2006) Vicarious Learning and Case-based Teaching of Clinical Reasoning Skills (2004–2006) [online], http://www.tlrp.org/proj/phase111/cox.htm (Accessed 25 June 2013).

de Waard, I. (2011). Explore a new learning frontier: MOOCs. Retrieved from Learning Solutions Magazine website: http://bit. ly/mSi4q

Dukes, DE 2001, ‘What You Should Know about Direct-to-Consumer Advertising of Prescription Drugs’, Defense Counsel Journal, 68, 1, p. 36, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, (Accessed 24 June 2013).

Ebbinghaus, M (1913) Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. (translated by H. A. Ruger and Clara E. Bussenius) 1913, (New York: Teachers College Press),

Edudemic (2013) A simple guide to 4 complex learning theories. http://www.edudemic.com/2012/12/a-simple-guide-to-4-complex-learning-theories/ (Accessed 23 June 2013)

E-Learning Council (2013) Overcoming the Ebbinhause Curve – How we soon forget. http://www.elearningcouncil.com/content/overcoming-ebbinghaus-curve-how-soon-we-forget. (Accessed 23 June 2012)

E-Marketer (2013) UK Tablet use sees robust growth. http://www.emarketer.com/Article/UK-Tablet-Use-Sees-Robust-Growth/1009857 (Accessed 23 June 2013)

Engineer Online (2012) ‘Smart pill containing microchip tracks adherence to medication’ 2012, Engineer (Online Edition), p. 12, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, (Accessed 26 June 2013).

Hammersley, M. (1992) What’s Wrong with Ethnography. London: Routledge.

Hayes, R.B., Taylor, D.W., Sacket, D.L. (1979) Compliance in health care. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Horne, R., & Weinman, J. (2002). Self-regulation and self-management in asthma: Exploring the role of illness perceptions and treatment beliefs in explaining non-adherence to preventer medication. Psychology and Health, 17, 17–32. doi:10.1080/08870440290001502

Hughes, G. (2007) ‘Diversity, identity and belonging in e-learning communities: some theories and paradoxes’, Teaching in Higher Education, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 709-720.

(access 24 June 2013)

Inkpen, K.M. (2000) Designing Handheld Technologies for Kids, Personal Technologies, 3(1-2): 81-9.

Kerfoot, B.P., Armstrong E.G., O’Sullivan P.N. (2008) Interactive spaced education to teach the physical examination: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:973–978.

Kerfoot, B.P. (2009) Learning benefits of on-line spaced education persist for 2 years. J Urol 2009;181:2671–2673.

Kerfoot, B.P, Kearney MC, Connelly D, Ritchey ML. (2009) Interactive spaced education to assess and improve knowledge of clinical practice guidelines: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg 2009;249:744–749.

Kerfoot, B.P, Lawler EV, Sokolovskaya G, et al. (2010) Durable improvements in prostate cancer screening from online spaced education a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2010;39:472– 478.

Kerfoot, B.P., Baker, H., (2012) An Online Spaced-Education Game for Global Continuing Medical Education: A Randomized Trial. Annals of Surgery Volume 256, Number 1, July 2012. pp.1227-1232 www.annalsofsurgery.com

Kerfoot, B.P., Baker, H., Pangaro, L., Agarwal, K., Taffet,G., Mechaber, A.J., Armstrong, E.G. (2012) An Online Spaced-Education Game to Teach and Assess Medical Students: A Multi-Institutional Prospective Trial. Technology and Learning. Academic Medicine, Vol. 87, No. 10 / October 2012 pp. 1443 – 1449

Kirkup, G. (2001) Getting our hands on IT. Gendered inequality in access to ICTs. Conference paper at Gender and Virtual Learning, Hagen, Germany.

Kit Yee, A, Moon, G, Robertson, T, DiCarlo, L, Epstein, M, Weis, S, Reves, R, & Engel, G (2011), ‘Early Clinical Experience With Networked System for Promoting Patient Self-Management’, American Journal Of Managed Care, 17, 7, pp. e277-e287, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, (viewed 19 June 2013).

Koller, D (2012) What we’re learning from online education http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=U6FvJ6jMGHU (Accessed 24 June 2013)

Laurillard, D. (1993). Rethinking university teaching: A framework for the effective use of educational technology.

Lave, J, and Wenger, E. (1991) Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

New Media Trend Watch (2013) http://www.newmediatrendwatch.com/markets-by-country/18-uk/154-mobile-devices (Accessed 23 June 2013)

NHS Choices. Health A-Z. Asthma. http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/asthma/Pages/Introduction.aspx (Accessed 23rd June 2013)

Offer, D, Ostrov, E., Howard, K.I. (1977) The Offer Self-Image Questionnaire for Adolescents. A manual, revised. University of Chicago, Illinois.

Open Learn (2013) Design in a nutshell. http://www.open.edu/openlearn/science-maths-technology/engineering-and-technology/design-and-innovation/design/design-nutshell (Accessed 26 June 2013)

Picard, R, Papert, S, Bender, W, Blumberg, B, Breazeal, C, Cavallo, D, Machover, T, Resnick, M, Roy, D, & Strohecker, C (2004) ‘Affective learning – a manifesto’, Bt Technology Journal, 22, 4, pp. 253-269, Science Citation Index, EBSCOhost, (viewed 24 June 2013).

Perlin, K. and Fox, D. (1993) Pad: An Alternative Approach to the Computer Interface, Proceedings of SIGGRAPH ’93:20th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, 2-6 August 1993, Anaheim, California, USA, 93:57-64.

Petrie K.J., Perry, K., Broadbend, E., Wienman, J (2012) A text message programme designed to modify patients’ illness and treatment beliefs improves self-reported adherence to asthma preventer medication’.

Punch, K.F. (2006) 2nd Edition. Developing Effective Research Proposals.

Resnik, M and Chang, A (2008) Tinkering Together: enabling synchronous creativity and distributed collaboration for kids, MAS 712 Technologies for creative learning.

Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) of Great Britain. (1997) From compliance to concordance: achieving shared goals in medicine taking. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain

Sawyer, S., Rosier, M. J., & Phelan, P. (1995). The self-image of adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 16(3), 204–208.

Sharples, M., Corlett, D. and Westmancot, O. (2002) The design and implementation of a mobile resource, Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 6: 220-34.

Soloway, E, Norris, C, Blumenfeld, P, Fishman, B, Krajcik, J, & Marx, R 2001, ‘Handheld Devices are Ready-at-Hand’, Communications Of The ACM, 44, 6, pp. 15-20, Business Source Complete, EBSCOhost, (Accessed 24 June 2013).

Stenhouse, L. (1981) ‘What counts as research?’, British Journal of Educational Studies, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 103

Scherman, M, & Lawhagen, O (2004), ‘Drug compliance and identity: reasons for non-compliance : experiences of medication from persons with asthma/allergy’, Patient Education & Counseling, 54, 1, pp. 3-9, CINAHL, EBSCOhost, (viewed 12 March 2013).

Siemens, G. (2006). Connectivism: Learning theory or pastime of the self-amused.Retrieved February, 2, 2008.

The Student Room (2013) http://www.thestudentroom.co.uk/ (Accessed 26 June 2013)

Vernon, J.F. (2011) Practice-based research in e-learning (H809). Tutor Marked Assignment 1 (TMA01)

Vernon, J.F., and Kerfoot, B.P. (2013) Skype conversation on the use of e-learning in healthcare in relation to people with chronic illnesses. Considered H809 TMA01. (Unrecorded)

Wang, M., Shen, R., Novak D. and Pan, X. (2008) ‘The impact of mobile learning on students’ learning behaviours and performance: report from a large blended classroom’, British Journal of Educational Technology.

Webb, S (2011) ‘Attacks on asthma’, Nature Biotechnology, 29, 10, pp. 860-863, Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost, (viewed 12 June 2013).

Wokasch, M. (2010) Pharmaplasia. Wokasch Consulting LLC.

APPENDIX ONE

How to define asthma

MODERATE PERSISTENT – IN THE RESEARCH GROUP (aboutasthma.com)

Your asthma severity is classified as moderate persistent asthma when:

With moderate persistent asthma, you will need daily asthma medication with anti-inflammatory properties, as well as a second medication. You are able to gain control of your asthma with two medications, what we call the ‘blue one’ and the ‘brown one’. The brown one, the inhaled steroid, you take a couple of puffs in the morning and a couple at night. The blue one, the reliever, or what in North America they call the ‘rescue’ inhaler, you take as required Source: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Accessed: May 20, 2010. Expert Panel Report 3 (EPR3): Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma |

APPENDIX 2

|

% =/-5% too ill to attend ‘profound’ SOTON 17000 undergraduates First years 5,000 – 5,500 |

Total Soton 9.5% |

Total Soton 11.5% |

First Years 9.5% |

First Years 11.5% |

Across4 UK universities |

|

Approx: students with asthma in the undergraduate population |

1,615 |

1,955 |

475 |

575 |

64,500 |

|

Describing themselves as: 41% very mild |

662 |

801 |

195 |

234 |

26,445 |

|

27% mild |

436 |

528 |

128 |

155 |

17,415 |

|

19% moderate |

307 |

371 |

90 |

109 |

12,255 |

|

11% severe (Wales et al., 2011) |

178 |

215 |

52 |

63 |

7,095 |

|

Moderate to severe likely to be: |

485 |

586 |

142 |

172 |

19,350 |

|

48% think they are at risk (Asthma UK) |

232 |

263 |

68 |

82 |

3,405 |

|

53.7% smartphones by 2014

|

125 |

141 |

37 |

44 |

1,829 |

|

less 4% self exclude from digital devices |

120 |

135 |

36 |

42 |

1,756 |

University of Southampton

Of an undergraduate population at the university of Southampton of 17,000 UK asthma statistics (Asthma UK, 2013) would suggest that between 1 in 10 and 1 in 12 are asthmatic (in a school population 1 in 12 has asthma, while there are 1 in 10 in the general population). Of these 5% have severe asthma and are unlikely to be attending university. This would suggest that between 9.5% and 11.5% as asthmatic. So between 1,615 and 1,955 asthmatic, of whom 662 to 801 likely to say that they are very mild and from 436 to 528 mild so have no medication, or a reliever at most (if they’re right). Between 307 and 371 moderate and 178 to 215 severe – so likely to be on a reliever at least at one end of the spectrum and a preventer too towards the more persistent or severe levels. i.e from 485 to 586. Of these 232 to 263 are likely to think they are ‘at risk’ (Asthma UK). Horn (1992) suggests that patients who admit to poor compliance may be more amenable to compliance modifying strategies; EU funded research into asthma has shown a significant willingness of those with this troublesome disease to take part in research (Cerveri et al., 2013) Whilst use of a smartphone does not define a person as digitally literate a self-reporting interview will isolate those who are … which might be, given use of e-learning in higher education, most of this group. A further reduction is given to exclude some who will not use these devices.

Potentially conducted across four universities:

- University of Southampton. 17,000 students.

- City University, Finsbury, London. 17,000 students. Urban

- University of Cumbria in Lancaster and Newton Rigg, Penrith. 10,500 students. Rural

- University of Oxford. 20,000 students.

APPENDIX THREE

Benefits of a private site using Qstream

|

User admin |

Batch invite |

|

Batch enroll |

|

|

History – invite, enroll |

|

|

Delete |

|

|

Email issue mgmt |

|

|

User registration report |

|

|

Access to learner email addresses |

|

Reporting & analytics |

User tagging |

|

Management roles & reporting |

|

|

Management summary engagement emails (weekly) |

|

|

Engagement summary |

|

|

Engagement detail & export |

|

|

Learner performance summary |

|

|

Learner performance detail & export |

|

|

Snapshot analytics |

|

|

Trend analytics |

|

|

Question performance report |

|

|

Question performance answer matrix |

|

|

Question performance analytics |

|

Site admin |

Monitor site activity |

|

Monitor comment activity for site |

|

|

Site branding (logo, tagline, home page, Dashboard, URL) |

|

|

Site localization (site branding translations) |

|

|

Email branding (sender name, organization logo) |

|

|

Private site publishing privileges |

|

Course admin |

Manage comment activity for course |

|

Shut down courses |

|

|

Basic course branding (course logo, course title) |

|

|

Adv course branding (sender name, organization logo) |

|

|

Private course catalog |

|

|

Public course catalog listing |

|

|

Private, closed courses |

|

|

Open enrollment courses |

|

|

Control course ‘operations’ (spacing, locked/unlocked) |

|

|

Completion management (%, certificate, messaging) |

|

|

Assign authors, co-authors |

|

|

Assign moderators |

|

Learner experience |

Customized leaderboard gaming (email display, online display, invid, team, monthly, rollilng) |

|

Localization |

|

|

Mobile |

Native app with notifications |

|

Mobile interface |

|

|

Course authoring |

Course catalog description/listing |

|

4 question types (MC, MCA, T/F, FIB) |

|

|

Preview/validation of questions |

|

|

Security |

Auto login |

|

Data security |

|

Social & collaboration |

Assign course moderator |

|

Learners can post private or public comments |

|

|

Comment management tools |

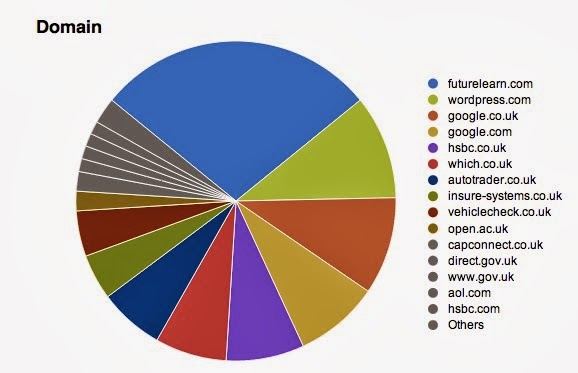

Web Sciences Visualizing Web usage

Fig. 1 My Google search History – last 24 hours.

Responding to an activity in the Future Learn open, MOOC from Web Sciences and the University of Southampton.

I use an iPhone, iPad, iMac and mini Mac. Nuts I know, but rotate or mix between them all across 24 hours depending where I am.

Due to current family hiatus something is always on so that whether it is a text message, Facebook message or email I can respond. Births, marriages and death are real and current reasons to feel that the private tendrils of connectivity are vital and vibrant, indeed with immediate family ages 6 to 87 all but a couple probably have a smart device in their pocket or at their fingertips as I type. Locations: all four corners of the UK, Cape Town, California and New Zealand. Sharing this and other FutureLearn programmes with some of them (10 nephews and nieces, three siblings, in-laws, step-parents and cousins).

What kind of sites do you visit most?

In the last 24 hours I have found, researched, priced and purchased a car. Vital as for family reasons we are going to be spending a good deal of time split between more than one household – not far in global terms or even for many living say in North America, but 137 miles with the M25 in between is a distance that can either take 2 ½ hours to cover of 4 or 5 hours.

Two days ago I posted a ‘Tutor Marked Assignment’ to the Open University module I am doing, aptly called The networked practitioner.

With that deadline met I have space to do other things. This includes, and it is not recognised here, is a regular two to three hours reading and note taking for a Masters degree in History. This traditional distance course is all books, reading and a monthly face-to-face day of lectures, seminars and tutorial – not having any, or much, online existence it is in e-learning and in 21st century terms ‘dead in the digital ocean of Web 2.0 learning’.

I have blogged since 1999 and in WordPress since 2007. The blog is many things: an e-portfolio, a niche social network, a platform for my current and sometimes considered thinking on a range of topics which currently include, in a blog each: e-learning, and the First World War – with previous content on creative writing, parenting, swim coaching – even books of condolences when a colleague has passed away, and ditto for my own parents.

What kinds of service do they provide you?

This snapshot shows how I use Which? online to make a purchase decision, then use online banking to manage funds, and to check and purchase, in this case, car insurance. I blog niche topics, no longer a journal as such though I kept a diary for a couple of decades. If I took that up again it would be forever ink on paper to avoid the risk of content being stored and thus made available to anyone forever. I live online, learning online but also active in social network, more professionally in LinkedIn groups, less so in Google hangouts and strictly for immediate family and friends on Facebook.

Recently, having been an e-learning evangelist and purist I am happily returning to reading books and taking notes – though my preference is to have the eBook for all the tricks and habits I have developed highlighting, grabbing, bookmarking, sharing and noting stuff as I read. I will photo printed pages to mash-up and annotate rather than mark the printed page.

What interests of yours and what areas of your life is the Web involved in, or not involved in?

Over a decade ago a small band of us debated privacy and presence online and opted for considerable exposure – in those innocent days testing the water of spilling the contents of our brains to each other, to strangers, felt revolutionary and ahead of the curve. Though this ‘behaviour’ has changed I continue to blog continuously, and to join in multiple forums as my approach to learning, like language learning, is to immerse yourself in it. Given a background in TV and video production my ‘moving image’ pressence has been limited to excerpts from professional work. I feel I will be embracing DIY production once more iminently – a tough adjustment as I came through the production ranks nearly three decades ago learning the practicalities of video shooting and editing and coming to rely on others to do this rather than as I did in the earliest part of my career doing it all myself. We live in a DIY ‘user generated’ culture were authenticity means you shot and edited the content yourself. All that I need to refresh or learn can be found online, much of it for free.

Academically I am venturing towards academia as an observer of how others behave because of what the Web affords, though my inclination as a ‘doer’ and participant might simply see my blogging turning into a broadcast – I have a drama-reconstruction project related to the First World War ‘in development’.

Web Networks – from the micro to the macro

We are each unique – our brains make us so. At the microlevel the network in our heads is then tickled out into the the Web in, at first. the simplest of ways. Our first post, our first comment is that first baby-step. Unlike our firsf steps though, online everything we do is saved, is monitored, is shared. It takes on a life of its own. Multiplied billions of times now many millions of us have learnt to crawl, then walk, then run online. As we are virtual we can split into many versions or parts of ourselves too – the professional and private the immediate split, but then into hobby groups and as here, a study group. The network of networks is a living thing that mathematics can help to weight and categorize, even to visualise, but crucially – the point made here, humanising the maths requires the insight of someone asking questions, seeking to interpret what it taking place. I see currents in a digital ocean that transpires into a cloud that then precipitates digital artefacts in a myriad of other places. Others, like Yrjo Engegstrom, see the growing tendrils of a funghi. Either way it is fascinating to condense, simplify and sharing the thinking.

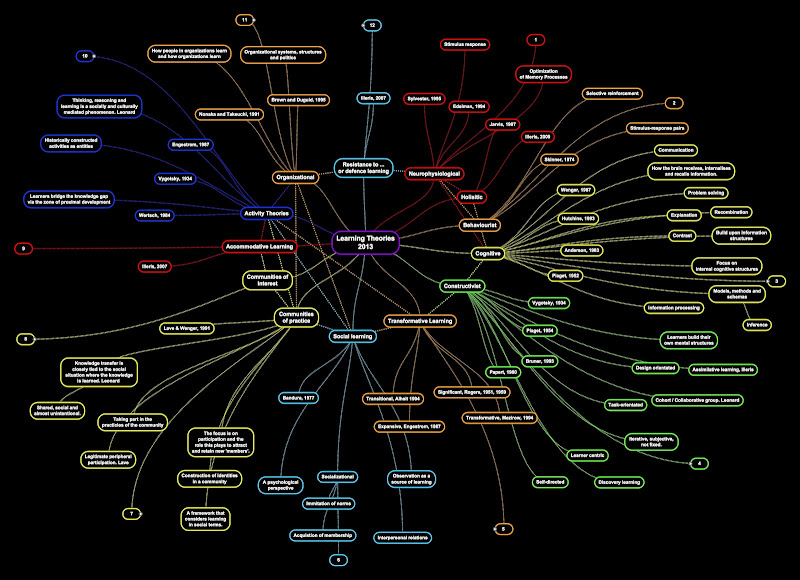

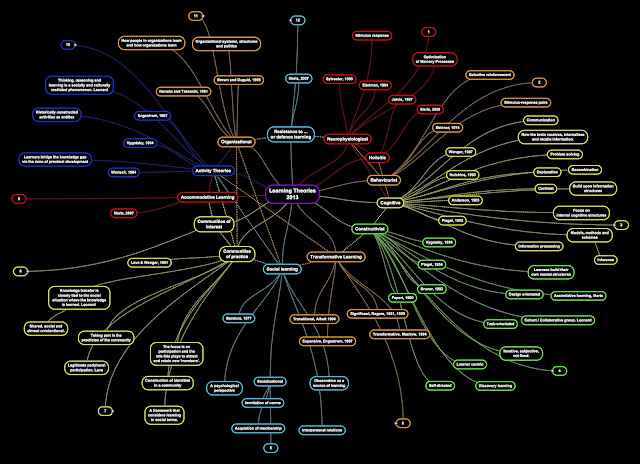

13 Learning Theories in a SimpleMinds mind map

Fig. 1. Learning Theories. Click on this and you can grab the original in a variety of sizes from the Picasa Web Album where it resides. (Created using SimpleMinds APP)

In an effort to impose some logic these are now grouped and various links also made. The reality might be take a large bowl of water then drip into these 12 coloured inks. The reality of how we learn is complex and will only be made the more so with fMRI imaging and advances in neuroscience.

My favourite Learning Theory here is one that Knud Illeris (2009) came up with – not learning at all, resistance too or defence learning. You just block it. That’s how I did 9 years of Latin and can decline how to love a table – I have no idea anymore what ‘ramabottom’ or some such means either. Ditto French as taught before secondary school and Chemistry – right or wrong, tick and box in a multiple choice each week. Still, for someone who couldn’t give a fig for either this approach got me through on a C grade. For French the ‘holistic’ approach worked a treat – French exchange, then back to hitch through France with some French guys who didn’t have a word of English, then got a job out there. Chemistry worked best with my Chemistry 7 set.

Activity Theory and Communities of Practice are surely in meltdown with the connectivity of Web 2.0?

The nodes and silos are too easily circumvented by each of us going directly to the source. ‘Community of Ideas’ works best for me.

Learning Theories

1) Neurophysiological – stimulus response, optmization of memory processes: Sylvester, 1995; Edelman, 1994; Jarvis, 1987.

2) Holistic – Illeris, 2009.

3) Behaviorist – Stimulus response pairs, Skinner, 1974.

4) Cognitive – Communication, how the brain receives, internalises and recalls information, problem solving, explanation, recombination, contrast, building upon information structures, focus on internal cognitive structures, models, methods and schemas, information processing, inferences.; Wenger, 1987; Hutchins, 1993; Anderson, 1983; Piaget, 1952.

5) Constructivist – Learners build their own mental structures, design orientated, assimilative learning (Illeris, 2009); task-orientated, cohort/collaborative group. Leonard, 2010): Vygotsky, 1934; Piaget, 1954; Bruner, 1993; Papert, 1980.

6) Transformative Learning – significant (Roger, 1951, 59); Transformative (Mezirow, 1994); Expansive (Engestrom, 1987); Transitional (Alheit, 1994).

7) Social – Socialization, a psychological perspective, imitation of norms, acquisition of membership, interpersonal relations (Bandura, 1977)

8) Communities of Practice – The focus is on participation and the role this plays to attract and retain new ‘members’; knowledge transfer is closely tied to the social situation where the knowledge is learned, (Learnard, 2010); shared, social and almost unintentional; legitimate peripheral participation (Lave, ); taking part in the practices of the community. A framework that considers learning in social terms. Lave & Wenger, 1991.

9) Communities of Interest –

10) Accommodative Learning – Illeris, 2007.

11) Activity Theories – Learners bridge the knowledge gap via the zone of proximal development, Wertsch, 1984. Historically constructed activities as entities. Thinking, reasoning and learning is a socially and culturally mediated phenomenon. Learnard, 2010. Engestrom, 1987; Vygotsky, 1934; Wertsch, 1984.

12) Organizational – How people in an organisation learn and how organisations learn. Organizational systems, structures and politics. Brown and Dugiod, 1995. Noaka and Takeuchi, 1991.

13) Resistance to/defence learning – Illeris, 2007