Home » MA First World War

Category Archives: MA First World War

Rottingdean’s Great War

This morning I received a delightful surprise as glimpses of sun broke through the heavy winter grey and old Rottingdean revealed itself around its war memorial and pond. I parked next to the war memorial with its Roll of Honour to both wars, with Rudyard Kipling’s home of five years behind off the green – somewhere he abandoned as it became a popular destination for tourists seeking him out.

A short walk took me onto the South Downs behind Saltdean – a walk that could be greatly extended when doubling back you see to the sea, the iconic old windmill on the hill and in contrast the vastness of the massive Rampion Offshore Wind Farm on the Channel horizon.

The return through the edges of the town showed off the many bedroomed ‘executive homes’ of the last century with their Jags and Range-Rovers, as well as the apparently older properties along Tudor Close by the church and cemetery which turn out to be cottages created out of the 1920s Tudor Cottages Hotel. The Manor House dates back to the 15th century, the Black Horse pub to the 16th century whilst The Elms where Kipling lived is 18th century and the Grange and North End House (where Burn Jones lived and worked) are 19th century.

Much occurred in the late 19th century with Burn Jones and Rudyard Kipling residents and the boarding prep-school St.Aubyns which saw many of its students graduate to the likes of Eton.

My First World War interest saw me visit the exterior of the school (closed for five years and being developed into apartments and houses). Its abandoned and trashed interior can be seen online courtesy of an old boy who broke in a few years ago to take a look. The journalist, author and Scots Guards subaltern Wilfred Ewart was here 1900-1905 as was his friend George Wyndham.

My First World War interest also took me into the churchyard of the quirky St Margaret’s of Antioch with its nativity display still out in late January.

I spotted a dozen or so CWGC graves, mostly the class Portland stone, some private memorials. These include:

| Fireman H Bateman, died 20 May 1917 on the SS Tycho. Mercantile Marine. Steamer sunk by a U Boat off Beachy Head. Body recovered and buried here. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| 267153 Pte William H Chatfield, Royal Sussex Regimentand 458331 Labour Corps died 14 February 1919 ‘of sickness’ (age 20) Son of Mr and Mrs Herbert Chatfield of 9, The High Street, Rottingdean. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| 2nd Lieut. David Dennys Fowler, RFC Born 20 June 1897, Seawall, Glenelg, South Australia Son of James Fowler of Dyxcroft, Rottingdean and and Mary Harriet (née Morgan), both were born in south Australia. In 1898 David’s six year old brother died. At some point in the next year or so the family moved to England. 1901 Albert Gate, Knightsbridge with his parents. His father was a ‘merchant grocer’ (employer) from south Australia. In 1909 a younger brother James was born (the family was by then living in Surrey). At the 1911 Census, Dennys, age 13, as he is known, was at school, Wavetree House, Furze Hill, Hove, Brighton, the census sheet showing 20 boys ages 12 to 13, of whom two were born in India, and Dennys in Australia. He then went to Harrow, was part of the OTC, leaving in December 1914. Although war had broken out to he took up at place at Trinity College, Cambridge. He had only just matriculated when his mother died on 14 November 1915 in Wimbledon. On 13 January 1916 he applied to become a flying officer. He gained his Aero Certificate in a Maurice Farman Biplane 29 May 1916 at Military School, Catterick Bridge. Second Lieutenant David Dennys Fowler reported from England and posted to No. 1 Squadron, A.F.C. (Australian Flying Corps), at Heliopolis on 4th September, 1916. Fowler was wounded on 5 October when his BE2c was hit by anti-aircraft fire while on reconnaissance with 2Lt J Hutchins as his observer, who escaped unhurt, but Fowler was sent to hospital in Tigne, Malta on 5 October 1916 with gsw to left foot. In December 1916 he was invalided back to England and attached to No. 78 Squadron, R.F.C. Text supplied by Chas Schaedel and the South Australian Aviation Museum History Group On the night of 17 March 1917 he was flying a B.E.2s Serial number 7181 on a Zeppelin patrol after an air raid. He was turning too near to the ground, causing the left wing tip to touch and the plane crashed about one and a half miles from Telscombe Cliffs Aerodrome and was killed. https://ww1austburialsuk.weebly.com/rottingdean.html He was buried in St.Margaret’s of Antioch Church, Rottingdean on 20 March 1917. Grave inscription: In His Twentieth Year With Every Promise Of Happiness Before Him He Gave His Life To His Country Sources: Australian Birth Index; UK, Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914-1919; British World War I Medal Records. Died in Salonika; England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995; Great Britain, Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificates, 1910-1950; 1901 England Census; The Street of Brighton and Hove; Virtual War Memorial, Australia. |

| Image to add |

| 67450 Pte Reginald W King, The Labour Corps formerly formerly G/3064 with Royal Sussex Regiment died at home 3 November 1918 (age 32) Son of Henry and Lottie King of 29, Quebec Street, Brighton. Husband of Mrs Daisy King of 2, Rifle Butt Road, Rottingdean. |

| Lieut. William Oliver Redman-King (special list) Born in Brighton. Died of pneumonia at home 28 February 1919. Son of Dr. J. B. and Mrs Annie Louise Redman–King of Weetwood Hall, Leeds, Yorkshire. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| Image to add |

| Serg.Maj. J H Rose, RFC, died 28 January 1916 |

| Image to add |

| Maj. Cuthbert R Rowden RAF/Worcestershire Regiment 78th Sqdn. Formerly with the 5th Worcesters. Died at home 20 April 1918 (age 21) Son of Arthur Roger and Blanche Mary Rowden of Eastnor, Ledbury, Herefordshire. Husband of Mrs Frances Rowden of ‘Halcyon’, Redhill, Surrey. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| Fire Engineer J Short, Mercantile Marine S S Tycho died 20 May 1917. When the steamer was sunk by a U-boat off Beachy Head. Body recovered and buried here. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). A ninth unnamed WWI Mercantile Marine is also remembered here. |

I’ll return to Rottingdean to seek out the graves I failed to spot this time round. I will also slowly complete short profiles for each man who served and died. My starting place will be the Roll of honour for the Rottingdean War Memorial produced by Chris Comber in 2004. Where I can find a photograph of the person being remembered and a Pension Card and further family and service details I will feature these in a commemorative post to the ‘Remember on this Day’ pages of The Western Front Association.

Are you interested in gaining an insight into the early days of air combat?

Fig.1. World War One: Aviation Comes of Age

This free, open, interactive and connected online course is about to start. It runs for only three weeks and will take a couple of hours a week to do, a little longer to take part in, and as long as you like to indulge.

|

| From First World War |

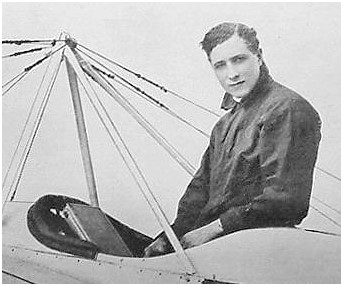

Fig. 2. Gustav Hammel – an early aeronaut who my grandfather saw fly in age 13

I’m doing it to refresh my knowledge from my late grandfather who say the very earliest aviators as a boy and then after 18 months as a machine gunner on the Western Front successfully transferred to the Royal Flying Corps to train as a pilot.

The course is led by a retired former senior RAF officer, Dr Peter Gray with whom I’ve already had a lecture courtesy of the MA in Military History, also with the University of Birmingham. His lecture was on how to read and review a book, and on how to write a competent essay. I’ve been respectively three, then one then ? marks shy of a distinction with my essays so he got me pointed in the right direction.

These courses are known as MOOCs for ‘Massive Open Online Courses’ because courtesy of the Internet they are global and can attract thousands of participants and ‘open’ because they are free to do and talk about … the other two are obvious. An off-putting acronym for a set of rich, multi-media webpages designed for learning? Lord Reith of the BBC, one of the founding fathers of the BBC, would have approved as these MOOCs from FutureLearn entertain, inform and educate.

Anyway, the course is about to start. It is open to anyone, and it is free. So see you there?

Why did Britain go to war in August 1914?

IN BRIEF

Britain was a global empire content to rule the waves and trade with her dominions and colonies, not least with the subcontinent of India. Where a choice needed to be made it was better to have Russia and France on friendly terms, especially as Germany post-Bismarck under kaiser Wilhelm II was seeking its ‘place in the sun’ – as a world power, dominant in Europe with a vast swathe of central Africa too. There was no need for the murder of archduke Franz Ferdinand to escalate however Germany, through the kaiser and Reich Chancellor pushed Austria-Hungary into what they at first hoped could remain a localised war, or at least one against Russia, or maybe against France to, but ideally not with Britain as well. Despite Germany’s lies and misjudgments, Sir Edward Grey did his utmost to bring the conflicting parties to conference: neither Austria-Hungary or Germany was having anything of it – they wanted war, Germany to resolve once and for all its fears on encirclement and Austria-Hungary to prove to all minority groups in its fragmented empire that it would stand up to anyone seeking national self-government. Britain did not have a cabinet agreement to enter the war until after Germany had invaded Belgium, however close talks and agreements were with both France and Germany. Nor in the British Expeditionary Force did it have a continental army – though it could and did very quickly draw from the dominions and colonies, as well as from volunteers.

SUMMARY

Britain went to war, reluctantly, in 1914 in response, once all efforts at mediation had failed, to the belligerent machinations of specific people in the Berlin leadership who exploited the murder of the Austro-Hungarian heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, no matter the risk of turning a local conflict into a world war, to challenge the status quo and so earn through conquest a position as a World Power.

Britain was reluctant, as were France and Russia, even Serbia to an armed conflict. Britain, expected or at least hoped to play a neutral role by Germany, through its Foreign Minister Sir Edward Grey and guided by the cabinet of a coalition Government of Conservatives and Liberals, did its utmost to mediate, through proposals for conferences and through direct and indirect diplomatic channels, in particular through briefing the German Ambassador in London, Prince Lichnowsky. Such efforts at mediation were delayed, ignored, obfuscated and stonewalled by the likes or the Reich’s Chancellor Bethman Hollweg, and Jagow, spurred on by the albeit oscillating and sentimental diplomatically inept German monarch, kaiser Wilhelm II. Documents identified for the purposes of explaining the actions, decisions and feelings of the participants in the lead up to what became a world war by Immanuel Giess in 1965 and Annika Mombauer some fifty years later, clearly show that Germany was inclined to try its hand, an apt metaphor that indicates the gamble they took, to escape the impasse, let alone the containment or encirclement which certain German leaders felt was keeping Germany back from its rightful place on the world stage.

Understanding why Britain went to war in 1914 necessitates understanding why Germany left Britain with little choice – the Cuckoo in the European nest wanted to dictate to all on the continent and would have happily left England on the other side of the Channel. There are three parts to this understanding: Germany’s rapid rise and maturity as an industrial nation contrasting with an immaturity or at best a splenetic political form of government; the position, character and demands of a handful of German leaders who dreamt of, planned and then willed continental if not world war and the efforts, and the ramifications of the ultimatum presented to Serbia by Austria-Hungary at Germany’s behest which led to diplomatic and Diplomatic efforts by Britain to prevent the localised war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia that would lead, the politicians knew, to a far wider conflagration.

IN A BIT MORE DETAIL

Britain went to war, reluctantly, in 1914 in response, once all efforts at mediation had failed, to the belligerent machinations of specific people in the Berlin leadership who exploited the murder of the Austro-Hungarian heir Archduke Franz Ferdinand, no matter the risk of turning a local conflict into a world war, to challenge the status quo and so earn through conquest a position as a World Power.

Britain was reluctant, as were France and Russia, even Serbia to take part in an armed conflict. Britain, expected or at least hoped to play a neutral role by Germany, through its Foreign Minister Sir Edward Grey and guided by the cabinet of a coalition Government of Conservatives and Liberals, did its utmost to mediate, through proposals for conferences and through direct and indirect diplomatic channels, in particular through briefing the German Ambassador in London, Prince Lichnowsky. Such efforts at mediation were delayed, ignored, obfuscated and stonewalled by the likes or the Reich’s Chancellor Bethman Hollweg, and Jagow, spurred on by the albeit oscillating and sentimental diplomatically inept German monarch, kaiser Wilhelm II. Documents identified for the purposes of explaining the actions, decisions and feelings of the participants in the lead up to what became a world war by Immanuel Giess in 1965 and Annika Mombauer some fifty years later, clearly show that Germany was inclined to try its hand, an apt metaphor that indicates the gamble they took, to escape the impasse, let alone the containment or encirclement which certain German leaders felt was keeping Germany back from its rightful position on the world stage.

Understanding why Britain went to war in 1914 necessitates understanding why Germany left Britain with little choice – this Cuckoo in the European nest wanted to dictate to all on the continent and would have happily left England on the other side of the Channel. Britain had historically always acted against a single power dominating continental Europe so a pressure point, if not conflict formed as Wilhelmine Weltpolitik moved from being an idea to a modus operandi.

There are three parts to this understanding: Germany’s rapid rise and maturity as an industrial nation contrasting with an immaturity or at best a splenetic political form of government; the position, character and demands of a handful of German leaders who dreamt of, planned and then willed continental if not world war and the efforts, and the ramifications of the ultimatum presented to Serbia by Austria-Hungary at Germany’s behest which led to considerable diplomatic and Diplomatic efforts by Britain to prevent the localised war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia that would lead, the politicians knew, to a far wider conflagration.

Germany, in contrast to its agrarian neighbours Austria-Hungary and France, was an industrial force with a rapidly expanding population; its leadership felt it needed room to grow into. Unified under the Prussian Bismark only 40 years earlier, by the turn of the century, as Hans Deltbruck put it in November 1899, ‘we want to be a world power’ which achieved ‘with England means peace; against England means – through war’. Britain, in this respect went to war because Germany dared to try aggression to achieve its aims once bungled efforts to secure Britain’s neutrality in 1924 failed.

Kaiser Wilhelm II felt Germany deserved and required the status of a Great Power too. Although a constitutional monarchy, like Britain, in Germany the kaiser wielded power with few checks. In the case of the kaiser this was unfortunate as this wilful man wished upon himself the role of a great Prince of Peace and a great warlord. (Geiss, 1965). His oscillations between the two could be tipped in favour of war as the Reich Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg managed, for example not allowing the kaiser to apply the brakes in the final moments before the outbreak of war. () Whilst according to Michael Freund, Franz Fisher’s made Bethman Hollweg out as being like Hitler is somewhat extreme, it is nonetheless the case that it was The Reich Chancellor’s will and actions, in his own words the ‘house of cards’ that he constructed, that built a position against which Britain had to act, in the final analysis when Germany breached Belgium neutrality, though it was to support France that Sir Edward Grey, the British Foreign Minister, with the agreement of a split Conservative/Liberal Cabinet, presented Britain’s ultimatum to Germany. Bethmann Hollweg did not act alone, the machinations of both Jagow and Moltke significantly drove Germany’s aims to force Austria-Hungary into a local war with Serbia, even though, indeed because, this would bring Russia into the fray and in turn initiate the Schlieffen plan that required the massive and equipped German army to attack France through Belgium. Such behaviour had been in the air since the end of the previous century () and on the cards since 1907 (). It was born out of Germany’s fear of encirclement and of Russia’s burgeoning might (). Fears felt by those in power in a Reich that lacked any constitutional provision for formal deliberation of such problems and now devoid of Bismarkian ‘Realpolitik’ (), the ‘politics of sentiment’ () the way the kaiser’s rule is described. Lichnowsky described to Bethmann Hollweg Jagow’s ‘misguided’ belief that Russia would stay out of the war for a few years yet – but it was lack of guidance, or the ability or means to listen to and act on advice that allowed a handful of people in Germany’s Ministry’s to believe the outcome of their actions and the subsequent war would be an mighty Germany at the centre of Europe and of Africa.

The Sarajevo Crisis brought about by the murder of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire should have no more brought Britain into armed conflict in continental Europe than the First and Second Balkan Wars. () Here, at the edge of Europe, with the desire for national self-determination being achieved at a cost to the Ottoman Empire () the very same movement threatened Austria-Hungary, itself ruled by a monarchy that clung to its dynasty with its threadbare grasp on its multivarious peoples and allied to the second most conservative nation after Czarist Russia, namely Germany. The murders of FF and SC gave Moltke the ‘slogan for a great war’: the excuse to flex considerable muscle. Britain, with the Foreign Minister Grey pivotal, could not have known or believed how duplicitous Germany could be, though expert insight and analysis had been and would be provided by Sir Eyre Crowe: Germany had ambitions and the means for aggrandisement both in Europe and Africa. ‘Either Germany is definitely aiming at a general political hegemony and maritime ascendancy’, Crowe advised in 1907, ‘threatening the independence of her neighbours and ultimately the existence of England, or … is seeking to promote her foreign commerce, spread the benefits of German culture’. Here Crowe elucidates the dichotomy that was this fledgling cuckoo at the beginning of the 20th century: on the one hand a 20th century commercial and cultural powerhouse on the other a 19th even an 18th poltical entity where the likes of Bethmann Hollweg, according to Erdman () could dream up an ‘eighteenth century cabinet war’. Repeatedly Grey took the initiative to see if the issues could be resolved, the most important proposal on 26th July for a four power conference in London between those countries which were not directly involved: England, France, Italy and Germany (g93,94). Germany refused thinking of it as tantamount to an ‘Aeropagus before which Austria would be held’ (g90) With delay only likely to play into the hands of the mediators gp. 270 Moltke took things into his own hands and informed Lt. Colonel Biernarch the Austrian-Hungary Military attaché in Berlin to mobilise immediately.

Metaphors on the one hand help with ‘meaning making’ and are used to help explain the complex even though they evoke the bias of their authors. Even a phrase as seemingly innocuous as ‘Britain goes to war’ suggests something far less troubled, debated over and contested – war, especially on the scale and for the duration expected – requiring millions of men and many years rather than a few months to resolve, was the last thing that Britain, let alone France, Russia or even Serbia desired. In this respect Britain did not so much go to war, as have war thrust in her face with the fait accompli the German leadership, Jagow in particular, pulled off by getting Austria-Hungary to get on with what her belligerent partner wanted and open the conflict with Serbia by bombarding Belgrade. Buchanan suggested to Grey that Britain would be ‘dragged’ into war, a century later the historian Christopher Clark (2011) describes how the countries ‘sleepwalked’; reading the original documents however you see that Britain and the other leading nations made a ‘conscious decision’, Geiss’s phrase (1965) and that in Britain’s case this was to make a stand with France against an aggressive Germany that felt that duplicity rather than diplomacy, and conflict rather than conference, was the way to achieve the aims of a nation’s leadership. Britain took a reasoned, and for the times the only course of action possible, when every conceivable effort to prevent war had failed; ‘going to war’ was the consequence of failing to postpone the ‘local’ war and get the parties to mediate – an impossible task given that only Germany had the means to start, delay or avert this ‘localised’ war between Austria-Hungary and Serbia.

Britain could act, having the immediate means to do so with the Fleet and the British Expeditionary Force and having, only with German’s breach of Belgian neutrality, Cabinet support, not without resignations and abstentions, to do so.

What Grey did, by committing, was to refuse to remain neutral as Germany had hoped, and so to remove one of the cards that would cause Bethmann Hollweg’s ‘House of Cards’ to collapse (g340) – the neutrality of the British Empire. Moltke would get the ‘showdown’ he had desired, to use another metaphor that places Britain and Germany like a couple of barefist fighters in the ring, a metaphor that puts at arm’s length the reality, brutality, and totality of what the players knew would be calamitous. The usually misquoted HGWells’ phrase, ‘the war that will end all war’ – the title to a pamphlet he wrote in November 1914, expresses what all the leaders of the combatants understood – that this would be a war on a scale like none that had gone before, a risk the German leadership wanted to take, opening a Pandora’s Box () that a century later remains ajar. Although it was the invasion of aliens that HGWells wrote about in his fiction, several other authors had written about a fictional invasion of Britain by Germany, something that initially the Cabinet and British Military leadership planned for and what was seen as an eventuality should Germany have been successful at conquering France and Russia on the continent. In its position as the dominant and established World Power, it was the British Empire that felt it had to meet the obligation to support France, not leadt because consideration had been given to alternative outcomes: France and Russia defeating Germany leaving the defensive alliance in tatters and other parts of the British Empire vulnerable. Ultimately Britain alone did not ‘go to war’, but rather the British Empire, with Kitchener as its military leader, a stalwart of successful colonial rule in India and of battles in Sudan and Southern Africa, with dominion and colonial forces to call upon, blocked Germany’s way to Paris. Having paved the way for seeking common ground on fireign policy in 1904 gp. 274 Paul Cambon now asked Grey to reconsider their correspondence in 1912 (g148) and Poincare attempted to make it clear to Bertie that only an unequivocal of England’s support could save the peace.

With Britain’s own issue of internal national self-determination to manage, the question of Irish Home Rule and the Protestant counties of the north, postponed and with parliament’s and the cabinet’s support to do so, Germany was presented with the British ultimatum, ironically after all the prevarications of this issue when it came to Austria-Hungary and Serbia, with a short timescale – not that there could possibly have been any further reason to hope for or expect mediation.

Britain had not declared her position too late, rather she had, in hindsight naively, left the door open for as long as possible for mediation – the extent to which German leaders, Bethmann Hollweg and Jagow purposely lied about Germany’s role and actions in relation to chivying Austro-Hungary into war with Serbia and deliberately stymied British efforts to bring the Powers to conference has only subsequently been fully realised (). Though the evidence was lacking, advice and insights from the likes of Buchanan, Rumbold, Nicholson and Crowe from Britain, as well as from Poincare and Sazanov from France and Russia respectively, must have come close to confirming Grey’s fears regarding Germany’s desire to be and to prove that it was a World Power.

Who wants to commemorate the First World War?

We should use the ‘connectedness’ of Web 2.0 to buddy up with six other people each from, for example, Germany, Russia, France, Serbia, Turkey, South Africa, Newfoundland, Belgium, Australia, Portugal, Japan, Italy … and more, to take in the 37 countries that threw their people at the artillery, machine gun fire, gas and barbed wire between 1914 and 1918 and then reflect on whether we are doing enough in 2014 to prevent violent conflict on any scale, anywhere. But we should not dictate, or tut tut if the response in Germany is different to ours. This has been the problem of the 20th century in families as in politics – expecting everyone to be like you, instead of recognising that we are each so different it makes me feel lonely to think about it.

Join me by making the commemoration ‘for the people, by the people’ – commemorate an ancestor or pick a name from a war memorial or from the records, and research their story. Post your content online then generate a Quick Response code and wear this. When people ask what it is say who you want to remember and how they can find out more … and even do the same themselves.

Who caused the First World War?

If a gas shell in the mud of Paschendaele in late October 1917 represents an absolute truth regarding the First World War, especially if you are perched behind a machine gun in a pill box just a few yards away, then this truth soon shifts as time passes, the gas is released and a morning breeze first backs, then slows, then changes direction moving ever further from the moment if truth. And thus, the politicians and historians play merry with the facts, in the form of official documents, as they are offered, revealed, exposed, disguised and refuted Try pegging where any of them stand on the truth of the causes of the First World War and you’ll have flags planted in every direction with little chance of getting back to the original point. And thus we have revisionists and anti-revisionists and their reasons for writing this way or that. The simple answer is that the problem Europe got itself into in 1914 was a mess. And from the perspective of a hundred years on I look through my timetelescope and want to damn the lot of them; but that was then, and now is now.

Leveraging mobile technologies and Web 2.0 tools to engage those with an interest in the centenary of the First World War in the stories of the people of the era using strategically placed Quick Response codes.

Jonathan Vernon at the Design Museum. J F Vernon (2011)

Access to the conference sessions is limited to H818 participants, MA ODE alumni, and IET staff.

If you fall into one of these categories and would like to register for the conference, please complete this short Registration Form.

Fig. 1. Lewes War Memorial, East Sussex, England J F Vernon (2011)

The problem with war memorials is that those named on them risk becoming forgotten words on a list.

By using the Web we can find out who these people named on the war memorials were and where they lived; we can try to put a face to the name and a story to the name … and then we can share what we find.

There are more than 54,000 war memorials in Great Britain, most of these put up after the First World War. There is barely a community without one. Significant interest already exists, especially as we approach the centenary of the First World War making this initiative a potentially easy one to add to what is already taking place.

Fig. 2. British Legion Poppy featuring a Quick Response Code

In his 2011 book ‘The Digital Scholar’ Martin Weller shares the thoughts of Brian Lamb to describe those technologies that ‘lend themselves to … the networked and open approach’ as ‘fast, cheap and out of control’.

It was with this in mind, taking an interest in the centenary of the First World War and obsession with war memorials that I started to think about using Quick Response codes as a personalized entry point to the Web that anyone could generate in order to share a story about someone who served in the conflict, and to do so both online and on the street.

Quick Response codes are fast, they are free and their potential in learning has yet to be realised.

Worn in this way, featured in the center of your commemoration Poppy, you can share directly with others the person whose life you wish to remember, as well as directing people to the content online and inviting them to ‘adopt’ a name from a war memorial themselves. Though exploiting the Web, this is designed as a ‘blended’ experience that uses face-to-face, community and classroom experiences, as well as taking people outside to monuments, buildings, streets and battlefields.

Esponsorvik (2014 )

Fig. 3. Toyota Quick Response Code and Using a TV remote control Espensorvik. Flickr

‘QR codes’ are a product of the car manufacturing industry. Faced with increasingly complex components, Denso, a supplier to Toyota, came up with what is a 2 dimensional bar code in the 1990s (Denso, 2010). Made free of patent, and using free software anyone can now generate their own unique QR code. You can even print them out on standardised sticky label stationery.

Fig. 4. Google Search ‘Quick Response Codes Education Images’ (2014)

There are a myriad of uses for QR codes, from embedding information that is read and stored by the device to a quick link to rich content online. Barrett, 2012). The interest here is to use QR codes to link to learning resources, in mobile, or ‘m-learning’ contexts in particular and for users to both read and write such context.

I liken QR codes to using your phone as a remote control to click to a TV channel (Fig 3) . You point a smartphone, or tablet at the QR code to read it and go instantly, pretty much, to a web page.

Their use in education in the last decade has been limited. ‘Refereed (sic) papers are few’ (Gradel & Edson, 2012), but between these and other published reports, suggestions can be made regarding their strengths or weaknesses.

If QR codes are to be used successfully then champions need to be identified to take up the cause in schools, colleges and local associations. Whilst QR codes use the power of the Web to connect people to rich content, that they may create themselves, a good deal of thoughtful planning will be necessary ‘in the classroom’, not just explaining how to make use of QR codes, but also working them in, where appropriate to current learning schedules where QR codes used in this way will meet clear learning objectives. Support online could be provided in a short eLearning module.

What has been shown repeatedly, in museums and ‘out in the field’, is that simply ‘put out there’ the QR codes are ignored (Gradel & Edson, 2012). An innovation such as this requires considerable promotion and support. This makes the idea of wearing your own QR code on a Commemoration Poppy all the more appealing, as each person becomes an ambassador on the ground, for that nugget of information, especially if they are responsible for creating and hosting that content.

The opportunity exists, therefore, mentored and guided by educators, with support online, for schools, colleges and associations to engage people in bringing the stories of those named on our war memorials alive. In this way a deeper and more meaningful connection is made with the past and our relationship to it.

Copyright © 2010, The New York Times Company. Photography by Jim Wilson

Fig. 4. Handheld curator: IPod Touches and visitors at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. (The New York Times)

According to the 2009 Horizon report (Horizon, 2009) the following would be of growing significance in teaching: mobile devices, clouding computing and the personal web. As an innovative approach, QR codes exploit all three of these developments.

Use of QR codes in learning however has had mixed results. Simply putting a QR code in front of a museum artifact, as they’ve done at the Museum of London and did at the Design Museum does not work (Vernon, 2013) – there is plenty already, there is little to attract or promote their use, not everyone has a smartphone or tablet of course and the technology is often not robust – ‘out of use’ signs are familiar. Outdoors QR codes added to signs in the South Downs National Park, for example, barely received a view a day during a three month trial and in some instances there was no signal at all (Kerry-Bedel 2011; South Downs, 2012).

Where QR codes have been successful is in targeted learning experiences in schools (Tucker, 2011; Gradel & Edson, 2012), where the affordances of the QR code have been exploited to form part of an engaging, constructive and collective learning experience. To be effective this initiative with war memorials requires galvanizing people to take part in a joint exercise – easier with a class in school or college, less easy with the general public unless it is through a national, regional or local community association or interest group.

Examples where QR codes work include where participants are ‘equipped’, and where they can take an active role, such as in ‘on the spot’ surveys or quizzes, where they are prompted into cooperative learning and where timely ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ are given. (Awano, 2007: Information Standards Committee 2008; So 2008; Robinson, 2010; Hicks & Sinkinson, 2011; Ryerson Library & Archives, 2012.)

K Lepi (2012)Copyright 2013 © Edudemic All rights reserved

Fig 5 . A Simple Guide to Four Complex Learning Theories. Lepi (2012)

The theory behind the idea of using QR codes in a mobile and open way, is that in the digital age ‘connectivism’ is the ‘modus operandi’. In this diagram (Fig. 5) from Edudemic (Edudemic 2012) traditional and digital theories are concerned. All are relevant, each has its place, with the digital environment offering new and additional approaches to learning.

Whilst traditional learning methods have their role in schools, lecture halls and with mature students too, the complete learning package requires a level and quality of interaction and connectedness that can only be achieved on the Web and be effective where the body of learners is large and their approach is open and shared so that knowledge acquisition comes through the challenges and rewards of such intercourse.

Connections won’t occur however unless they are nurtured. By way of example, wishing to support and promote the combat memoirs of my late grandfather John Arhtur Wilson MM (Vernon, 2012) a number of organizations will be approached up and down the UK in relation to his experiences in the Durham Light Infantry, Machine Gun Corps and Royal Air Force. The Web will both help identify, forge and maintain and develop first and subsequent connections in what would hopefully be, to be effective, a two way, shared, open and reciprocal relationship. The beauty of having content already online is that others can quickly view it and images, text and sound files, even video, adjusted to suit different audiences, or uses – and used freely where appropriate copyright permissions are given.

JFVernon 2010 from statistics from Jakob Nielsen (1999)

Fig 6 . Creators, commentators and readers – how use of the Web stacks up. Vernon (2010) after Nielsen (1999)

This degree of connectedness does not come naturally. Just as there can be no expectation that people will use a QR code because it is there – they won’t. With an innovative approach such as this promotion is crucial. Significant time, thought and effort need to be put into letting people know what is taking place and supporting their participation.

Only a fraction of a population are naturally inclined to generate content.

Jakob Nielsen (1999) would suggest that as few as 1% create content (Fig. 6). If content is therefore to be created by participants then very large numbers need to be made aware of the initiative. Online, openness helps when it is massive. Participation is improved where it is supported and moderated. Creators, commentators and readers each have a role to play.

The balance needs to be found between the qualities of a tool that is fast and cheap and where out of control means that something isn’t used in a way to benefit a formal learning requirement. On the one hand those who want to generate content can be encouraged to do so, while in a formal setting the intention would that everyone generates content of some form in order to receive feedback and assessment.

Fig 7. The Newcastle War Memorial by Sir William Goscombe John RA J F Vernon (2011)

The potential weakness of using QR codes are the requirement for participants to have a suitable device, say a smartphone or tablet and the possible communication fees when connecting away from a free wi-fi source – which is likely to be the case at a war memorial (Gradel & Edson, 2012).

Reading from and using a smartphone or tablet may also present accessibility issues, from the need for dexterity and reading content that isn’t offered in alternative forms, such as text sizes and background or audio alternatives.

There are many examples where local councils feel a war memorial or building is so important that they have invested in information placards on site (Fig. 7). As commemoration of those who served and died in the First World War is of local and national interest funding is potentially available to help support initiatives such as these through the Heritage Lottery Fund, while organizations such as the Western Front Association have funding for branch activities too.

If permission is required for personalization of a British Legion poppy using a QR code, then alternatives may be required, from working with other suitable groups such as the Imperial War Museum or Western Front Association to putting the QR code on a badge instead.

Where used in the field it is likely that a teacher would put out sets of QR coded markers in advance and collect them afterwards. Where a photograph in a town featuring before and after views permission may also be required if any kind of QR coded plaque or poster is to be put up. Other inventive ways to use a QR code would be to attach them to an obstacle course like trench experience where each code triggers elements of a task, sound effects or narrative in keeping with the setting. By way of example, at the ‘In Flanders Museum’ in Ypres a number of exhibits require the visitor to duck, crawl or crane their neck before supporting audio or lighting is triggered by a Near Field code in a bracelet.

Fig. 8. The memoire of a Machine Gunner and RFC Fighter Pilot. ‘That’s Nothing Compared to Passchendeale’

J F Vernon (1989-2014)

In his 2011 book ‘The Digital Scholar’ Martin Weller shares the ideas of Robert Capps (2009) who coined the term ‘the good enough revolution’ – in relation to creating and sharing content in an open culture. This precludes being prescriptive or from expecting perfection.

Whilst output on the First World War from the BBC, the Imperial War Museum or the Open University should understandably attain a certain professional standard, the kind of creation required of those research names on war memorials should take inspiration from that is more than just ‘good enough, from ‘pinning’ names from a war memorial to a home address, to ‘pinning’ submitted World War One photographs to Google maps over former battlefields, as well as numerous inventive YouTube videos and memoirs presented as blogs.

REFERENCE

Awano, Y (2007). Brief pictorial description of new mobile technologies used in cultural institutions in Japan. The Journal of Museum Education, 32(1), 17-25

Barrett, T (2012). 50 Interesting ways to use QR codes to support learning. (Last accessed 6th Feb 2014 https://docs.google.com/present/edit?id=0AclS3lrlFkCIZGhuMnZjdjVfNzY1aHNkdzV4Y3I&hl=en_GB&authkey=COX05IsF

Denso (2010a). QR Code Standardization. (Retrieved 6th Feb 2014, from http://www.denso-wave.com/qrcode/qrstandard-e.html )

Edudemic. Traditional Learning Theories. (Accessed 19th April 2013) http://edudemic.com/2012/12/a-simple-guide-to-4-complex-learning-theories/

Gradel, K., & Edson, A. J. (2012). Higher ed QR code resource guide.

Hicks, A., & Sinkinson, C. (2011). Situated questions and answers: Responding to library users with QR codes. Reference & User Services Quarterly, 51(1), 60–69.

Horizon Report 2009 (2009) Educause (Accessed 14th Feb 2014 http://www.educause.edu/library/resources/2009-horizon-report )

Information Standards Committee (2008) Section 3: QR code, Synthesis Journal. (From http://www.itsc.org.sg/pdf/synthesis08/Three_QR_Code.pdf )

Kerry-Bedel, A (2011) Smartphone technology – the future of heritage interpretation: Its in conservation (Accessed 14th February 2014 http://www.kbstconsulting.co.uk/QR/images/ITIC.pdf )

New York Times. The Best Tour Guide May Be in Your Purse. Article by Keith Schneider. 18 March 2010. Copyright © 2010, The New York Times Company http://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/18/arts/artsspecial/18SMART.html

Nielsen, J (1999) Web Usability

Robinson, K. (2010). Mobile phones and libraries: Experimenting with the technology. ALISS Quarterly, 5(3), 21–22

Ryerson University Library & Archives (2012). QR codes. Retrieved 6th Feb 2014, from http://www.ryerson.ca/library/qr/.

So, S. (2008). A Study on the Acceptance of Mobile Phones for Teaching and Learning with a group of Pre-service teachers in Hong Kong. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 1(1), 81-92.

South Downs (2012) Use of QR Codes (Accessed 14 Feb 2014 http://southdownsforum.ning.com/forum/topics/signposting-and-qr-codes )

Tucker, A. (2011). What are those checkerboard things? How QR codes can enrich student projects. Tech Directions, 71(4), 14-16.

Vernon J.F. (2012) (Blog Post) (Accessed 14th February 2014 http://machineguncorps.com/jack-wilson-mm/ )

Vernon, J.F. (2013) (Blog Post) Mobile learning at the Museum of London: QR codes and NFCs (Accessed 14th February 2014) http://mymindbursts.com/2013/11/10/molqr1/

Weller, M (2011) The Digital Scholar: How Technology is Transforming Scholarly Practice. 5% Loc 239 of 4873

NOTES AND LINKS

The teachers guide to copyright and fair use. http://tech4classrooms.org/2013/02/16/the-teachers-guide-to-copyright-and-fair-use-edudemic/

Lepi, K (2012) A Simple Guide To 4 Complex Learning Theories. Edudemic eMagazine 24th December 2012. (Accessed 14th February 2014. http://www.edudemic.com/a-simple-guide-to-4-complex-learning-theories/ )

LINKS

The Newcastle War Memorial by Sir William Goscombe John RA

Sir Douglas Haig by J P Harris (2008)

Created in SimpleMinds. get in touch if you’d like a copy. Download the SimpleMinds App for free.

Douglas Haig and the First World War (2008) J P Harriss

Nearly 600 pages that follow a chronology that is familiar. Insights on Haig are limited – perhaps reading Haig’s diary and a biography at the same time would help. This is written by a military historian with judgement of Haig’s command key. We get little insight into the man – if there is much a a personal life to probe. His diary appears to reveal little. What does come over is how often Haig was to blame for actions that were unlikely to succeed in doing much other than expending a good deal of munitions and men – time and time again he planned an offensive that would lead to a break-through, require cavalry support and put tens of thousands of men against barbed wire, machine guns and shrapnel. His greatest skill was to climb and keep climbing the ladder of promotion and to tread carefully around events which might have led to his being passed over for promotion … or his resignation asked for, or accepted.

My first read. A second read possibly to follow unless I can be pointed to a biography.

Notes as iPhone/iPad pictures with annotations (Studio) and a mindmap (SimpleMinds)

Britain had been preparing for war with Germany as is clear from manoeuvres, in this instance with both France and Russia, in 1912 (Harris, 2008:51). Perhaps the re-organisation of the Army to have the Expeditionary Force, however small, was part of an anxiety and vulnerability – had Britain not also contemplated conscription?

As the nature of artillery changed – longer range, great accuracy and a diversity of shells types from high explosives to shrapnel it is staggering that proper thought wasn’t given to how destroyed the land was over which the armies would have to travel.

Typo alert! Actually there are a couple more but I so no value

Where tactics have failed to deliver why did Haig persist? How could more of the same possibly get better results next time? What part of his mindset made him stick to this? Does he lack imagination? He appears emotionally dry or aloof – his relationship with his wife and family hardly suggests a person with a close emotional attachment.

Haig’s greatest skill and purpose was to climb to the top of the Army ladder – what he did or could do when he rose to the top was another matter. This isn’t what makes a great leader – he is like a career civil servant. But what would a hot headed, womanizing, gambler of a man done with this power? If Haig made mistakes they need to be considered and compared with other leaders on the Western and Eastern Fronts. Had Britain a leader like Foch, Neville, Falkenhayn or Holweg … or the Russian aristocrats would we have fared better or differently? And if we’d had Robertson rather than Haig?

History written by a military historian is different to history or biography – the audience here is expected to learn and potentially apply at staff level the lessons from past battles. Haig’s diary is revealing because in this supposedly private moments he is reveals so little: statements of the weather, not what this could mean, statement of events without reflection on what he did well or badly. Self-control in both his public and private life.

To understand Haig then we need to know who the alternatives might have been and whether in reality they could or would have behaved differently: Robertson, Du Can and Rawlinson are different men.

My impression is of a deluded fantasist with no one able or willing to stand up to him … not even Lloyd George. Haig, with Royal patronage and few competing for his role, could and would do as he pleased. He resented having to play second fiddle to the French. In the early stages of the war he ignored orders or requests with potentially dire consequences yet he got away with it.

Haig’s tactics: more munitions, human dynamism and officers of the ‘thruster’ type – people who would risk all regardless. Is there anything we can learn from Haig’s achievements as a polo player from this? What does it require to win at polo?

Haig pressed on with tactics that would leave many thousands dead for little gain and he wasn’t able or willing to question what he could or should do differently.

How clear did failure have to be to get Haig to change his tactics?

Failure of this kind should surely have seen Haig replaced? To what extend did his ‘moral fibre’, his otherwise untarnished character, make it less easy to remove him?

Overexcited, overoptomistic, blind to failure, forever looking beyond the horizon, convinced cavalry had a role, yet able to try gas and tanks … anxious for his peers and superiors to shower him in praise and his subordinates to be fawning …

Self-righteous and self-assured – did his religious beliefs permit his unstinting view of the world? He had the image of someone who deserved authority and respected it. He was fit, sober and in a stable marriage. He worked hard and played the game well. Born into a different age could he have survived? He lacks the flair of Montgomery or Churchill. Described as taciturn, to what degree might or could his asthma have been a controlling influence?

He looked the part and was fastidious about his health – what else could as asthmatic do in the early 20th century? Did he know what the triggers were, or had he learnt from experience to avoid certain foods and situations – not least smoking? Was he prone to chest infections?

Whilst those around him realised all talk of a ‘break-through’ was unrealistic, this is what Haig constantly planned for and expected. Or was it simply wishful thinking?

Step by step is what occurred … as a result from efforts to breakthrough? A case of shoot for the stars and hitting the moon? That in Haig’s eyes step by step would have equated to inconsequential nibbling?

Obsessive, selective, fixated, God-guided, controlling, cavalry-orientated, driven obdurate, blind … consistent, controlled, tempered, magisterial … aloof and with tunnel-vision.

Able to comprehend, but unable to bend? Unable to think of any alternative. The world around him changed, but Haig stayed resolutely in the 19th century.

Chance the way the leaders played off against each other? Men like so many bullets or sandbags, simply a resource to count then stack in the knowledge that there would be great losses but that these could be shored up?

He didn’t like to have his feather’s ruffled. He wanted the game played in his way with him in charge.

A hypocrite who would fail to come to the aid of others … yet others to come to the aid of him. Too good or important to warrant risking his men, or putting his men under another’s control and willing only at the last minute to seek help when things looked desperate and he had no choice.

Related articles

- Haig was no hero (machineguncorps.com)

- Museums watch: The poppy and Reading (getreading.co.uk)

- ‘Your Country Needs You’ (thesocialistway.blogspot.com)

- Alex Massie: War that changed a nation (scotsman.com)

- The First World War Pt.5 (detectingblackpool.wordpress.com)

- Canada and the First World War (anoctoberhorse.wordpress.

Myopic

From the perspective of 2013 the behaviours of those with responsibility for actions 1914-18 are myopic. How could they have possibly comprehended the feelings or needs of anyone in the front line? Or even had a grasp of the scale of what was taking place? It is too easy, natural for us 100 years later to have a perspective that is massively enlarged.

100 years ago it isn’t a case of everything occurring at a snail’s pace – it was slower, like stone.

Perhaps this is what a 21st century perspective offers – the extraordinary speed and quality of information that we get compared to the lack of clear or immediate data.

WWI MOOC

Fig.1 Underdtanding the Great War

As an MA student on the Bham First World War studies programme we are reading and then writing a book review on Niall Ferguson’s ‘The Pity of War’. The consequence for me is a significant growth in my library of First World War books, and eBooks such as this one. Meanwhile, with this contrasting worlds of real and virtual playing out in parallel workds I am doing the Open University MA in Open and Distance Education module H818: The Networked Practitioner. I’ve done three MOOCs. Is this how a campus based taught course at Bham lauches itself into 21st century education?

PR RELEASE

Posted on Wednesday 16th October 2013

The University of Birmingham is linking up with the BBC to create an academic first – a unique distance learning course marking the centenary of the First World War next year.

The ‘Wings of Modernity’ course, developed by the University’s Centre for War Studies in conjunction with the BBC, was announced during a press conference outlining the BBC’s forthcoming World War One Centenary coverage today (Wednesday 16 October). It will be a pilot Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) looking at the evolution of airborne conflict, published on the FutureLearn platform.

Controller of Learning Saul Nassé says: ‘The BBC continues to be excited about the development of MOOCs – Massive Open Online Courses that will enable mass participation in learning online. We are keen to explore opportunities with a number of University partners as part of our WW1 coverage. The first one to be developed will be with the University of Birmingham, the short course will cover the deployment of air power during the First World War and attitudes to the use of new technology.’

Dr Jonathan Boff, lecturer in war studies at Birmingham, commented: ‘This exciting initiative will give us a chance to share our passion for First World War history with the widest possible audience. It also enables us to continue our pioneering use of digital technology both to support existing students and to attract new ones. Students stimulated by the MOOC can easily pursue their interest by exploring our wide range of full-time and part-time undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, online and face-to-face, in war studies and the history of warfare.’

Director of the Centre for War Studies Dr Peter Gray added: ‘The University of Birmingham has, in the Centre for War Studies, the largest and longest-established centre for specialist research and teaching of the First World War anywhere in the world. It is also internationally renowned for excellence in the study of Air Power.

‘The ‘Wings of Modernity’ MOOC will bring together our strengths in both areas to allow students to explore, not only the Great War in the air, but also the impact the war had on aviation more generally, and more broadly still to examine developing attitudes to technology in a time of revolutionary change. Although we often take aeroplanes for granted today, the story of how we got to this point is a fascinating one whose roots lie in 1914-18.’

In a separate but related development, the Centre for War Studies is one of the Universities providing academic advice and support to the BBC’s digital content for the First World War centenary.

This will cover a range of material designed for audiences from as young as five years up to those as old as the war itself and is evidence of the commitment of both organisations to explaining the history of the Great War to the widest possible audience.

Notes to editors

Dr Jonathan Boff is Lecturer in War Studies at the University of Birmingham, where he leads the MA in British First World War Studies and an online-only MA in Military History by Distance Learning.

Dr Peter Gray is the Royal Aeronautical Society Senior Research fellow in Air Power Studies at the University of Birmingham and Director of the Centre for War Studies. He has published widely on a range of air power subjects from historical issues through to contributing to current debates on remote warfare such as the employment of drones. He has extensive practical experience from his time in the Royal Air Force and is in demand worldwide for his knowledge of air power history, theory and practice.

The Centre for War Studies at the University of Birmingham is one of the leading institutions of its kind in the United Kingdom. It brings together academics from around the globe to research and teach military history. With particular strengths in the study of the two world wars and the history and theory of air power, it offers a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate courses and maintains a unique network of alumni and associates active in the field of military history and war studies.

For media enquiries please contact Jenni Ameghino, University of Birmingham Press Office, +44(0)121 415 8134 / +44 (0)7768924156