Home » Somme

Category Archives: Somme

Bloody Victory: The Sacrifice on the Somme – William Philpott (my notes)

On how to cut a book of some 626 pages to 14 pages of notes. Each a nugget that had I not written them up like this I’d have them in the eBook version – but there is none. It is books such as this that are allowing me to clear the myths and cliché that have gathered about the history of the First World War over the last 100 years.

The next step here will be to seek original sources myself to get my take on it.

Bloody Victory: the sacrifice of the Some. (2009) William Philpott

|

Page |

Note |

Detail |

|

4 |

Churchill’s POV |

The World Crisis – one of Britain’s great historical myths. He had little to do with it. The luxury of dissociation. Familiar clichés: the product of a self-absorbed refusal to investigate the bigger picture, unimaginative and callous generals, ill-planned and futile offensive operations, high and unnecessary casualties, atrocious battlefield conditions, technophobe cavalrymen failing to appreciate the potential of new war-winning weapons. |

|

11 |

Deeper Pockets |

Falkenhayn hoisted by his own strategic petard having aimed at wearing France down over Verdun, the German army was worn away on the Somme. Germany realised that the enemy had deeper pockets. |

|

28 |

26.IX.1914 |

Fricourt Village marks the far point of the German advance north of the Somme – the front was ‘stalemating’. Hanotaux. Psychologie de cette guerre 26 augusr 1914, hanotaux, op.cit, p.80 ‘Modern war was turning out to be butchery’ The spade and the gun. |

|

29 |

Military School |

steel, weaponry, science and technology. Though a static battlefield a ‘vibrant and dynamic military school, as tactical innovation and technical novelty tripped over each other’. ‘Human lives still lay at the root of strategy’ |

|

30 |

Attrition stared in 1914 and reached its apogee in 1916 |

The French attack to take the village of Quesnoy-en-Santerre indicative of the ‘scientific’ battles to come. |

|

31 |

Problem of WW1 |

Small scale attacks aggregating into attrition dependent on management and resources, rather than hast and inadequate provisions. |

|

39 |

Kitchener |

Kitchener to Repington: the war would be long and its purpose would be to ‘wage war on a great scale’. Mobilise the empire’s resources. A war strategy to best place England when imposing terms of peace. The Times, 15 August 1914 Kitchener to Charles à Court Repington (who appears to have or got the ear of the leading players). He published French’s views on 14 May 1912 which brought down the Asquith government. |

|

THE 1914-1918 PERSONAL EXPERIENCES |

Lord K. usurped most of its duties without knowing http://archive.org/stream/firstworldwar19101repiuoft/firstworldwar19101repiuoft_djvu.txt On Aug. 3, with the approval of the editor of the Times, Mr. Geoffrey Robinson, I made the first proposal in the Press that Lord Kitchener, who was at home on leave from Egypt, should be appointed War Minister |

|

|

I was on the best of terms with Lord K. at the opening of |

||

|

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation |

He thought, in these circumstances, that the war would |

|

|

He allowed me to hint at the need for |

||

|

64-65 |

Haig in brief |

Enormity of the task Brought personal qualities to bear Intelligent Purposeful Determined Press cliché and stiff, formal photographs unrepresentative of the man he was? Born 1861 Clifton College Brasenose College, Oxford Sandhurst 1884 and top of his class Hard-working Self-disciplined Aloof A deep shyness Ambitious Self-assured Diligent Professional Reserved Aloof Deep Christian Faith India Had an interest in European soldiering Service experience under Kitchener in the Sudan (Might have Haig looked up to Kitchener the way Kitchener looked up to Gordon?) A protegé of Sir John French in South Africa ‘in need of a wife’ (Kitchener managed without one) Very aware of complexities of fighting for an ally on their land. |

|

70 |

Time, place, method |

An attack has three elements: time and place (strategy) and method (operations). |

|

94 |

Clausewitz on war |

Policy to bleed France to death at Verdun |

|

96 |

Falkenhayn and allies attrition |

Falkenhayn may have initiated a war of attrition, but it wasn’t lost on the allies. Kitchener had raised the New Armies with this strategy in mind. |

|

102 |

Haig had no choice |

By the Summer of 1916 wherever Haig attacked the enemy had fortified. |

|

106 |

The Somme planning in brief |

A battle plan that was confusing and a compromise Haig wanted to micro-manage Rawlinson’s plan was unsuited to the changing relationship with their French ally or actions of the enemy |

|

108 |

Kill Germans |

Rawlinson ‘bite and hold’; Haig desired mobile warfare. |

|

114 |

Fayolle on attrition |

Not attempting more than his artillery could comfortably support. |

|

118 |

Attrition …. on brala Haig |

Like Foch and Joffre, Haig and Rawlinson disagreed. Was the operation to be slow, methodical, materiel intensive and attritional, designed to grind down the enemey’s power of resistance until it collapsed? Or was it to be a sudden, powerful, disruptive thrust aimed at doing as much as possible in the first assualt and rapidly exploiting the resulting confusion in the enemy’s defence, as Haig intimated in his reaction to Rawlinson’s first proposal? |

|

120 |

earns crap in |

Few |

|

Haig stretches it too far |

Fewer guns per yard that at Neuve Chapelle or Loos |

|

|

124 |

Haig got plan for Somme wrong |

He strove to get it right. It was a concomitant of coalition planning as well as military mentality |

|

125 |

Cue from Joffre |

Haig took the cues from Joffre, though these prompts were shifting and contradictory, and further warped by Haig’s military logic. |

|

126 |

Haig too sanguine, Rawlinson more realistic |

At cross purposes with the French. Like Kitchener, who when asked when he though the war would end had refused to make a prediction merely intimating that it would start in earnest in April 1916. |

|

128 |

Foch on industrial war |

and the long haul |

|

129 |

Perceptive Chateris |

Strategic attrition was a key element of the plan for 1916 from the first conference at Chantilly. Charteris to his wife. ‘Fighting to wear down the German armies and the German nation’. |

|

132 |

An intrepid woman |

A female journalist managed to secure a pass from a town marshal then spent a week living amongst the 51st Highland Division. |

|

Material intensive |

The creation and support of ‘machine-gun armies’ … gas, flame-throwers, grenade-launchers, submachine guns, trench mortars, trench canon, fighter and bomber aircraft, tanks and self-propelled artillery. |

|

|

134 |

The world’s greatest trading infrastructure |

Four resources: manpower (men and women), industry, distribution of goods, finance … |

|

Kitchener – when the war would end |

||

|

135 |

Lloyd George |

His biography to date in a paragraph. Former lawyer. MP for Caernarfon Boroughs. Chancellor of the Excheque 1914. Minister of Munitions 1915. Self-important, determined, changeable, scheming, loquacious, argumentative. Pacifist to war-monger and advocate of the ‘fight to the finish’. |

|

137 |

Premature, duds, blinds |

Faulty guns and munitions in June 1916 |

|

The machinations of the city to keep the war economy afloat. |

||

|

140 |

Kitchener’s prediction |

Kitchener correctly predicted in 1914 that the real war would start in 1916. |

|

143 |

German interception |

German interception of telephone calls leading up to 1 July meant they had a good idea of what was going on. |

|

The prosaic nature of the role of the RFC supporting slow moving observation plains and shooting down observation balloons. |

||

|

145 |

Grinotage – nibbling |

The attritional nature of the battle spelled out in an 82 briefing document issued to French units. Reconnoitre, clear objective, coordinating, cohesion … foresight and practice. |

|

147 |

the best weapon for each job |

A hurricane of projectiles … The French had: howitzers to destroy trenches, machine-guns, observation posts, light mortars, larger calibre mortars … |

|

150 |

plans |

British assault tactics were more flexible than posterity acknowledged. |

|

151 |

Learning, engaging |

The idea of a ‘pushing forward at a steady pace in successive lines’ is untrue; the Fourth Army used deep formations in four waves with a high degree of flexibility. |

|

151- 152 |

training |

long route marches along tree-lined country roads, rifle and bayonet practice, grenade and machine-gun practice, gas mask training … unlike the French the British had no pre-war training infrastructure. Training built confidence, perhaps over confidence? |

|

177 |

French Tactics |

Foch’s attacking methods … Fayolle’s cautious and precise preparations. |

|

178 |

30th do well Somme |

Got a head start … co-ordination of artillery and infantry. |

|

Friendly fire kills Pickelhaube |

Picking up and putting on a pickelhaube as a souvenir a soldier is shot in error by one of his own men. |

|

|

180 |

Two tactical problems |

Isolated machine-guns and pockets of resistance |

|

182 |

La Briqueterie |

|

|

189 |

The myth of the Somme – Liddell-Hart |

For all the blame, when has the organised and effective German defence been considered? ‘The British did not fail by their own endeavours along, but in a gruelling flight with a professional, skilled and determined adversary’. |

|

196 |

Poor communications |

‘The slowness and uncertainty of communications meant that reports were generally out of date, incomplete or incorrect, and therefore difficult to interpret correctly’. |

|

202 |

Making tea in battle – 60 seconds |

Futile or stoical? |

|

203 |

German first aiders aid Tommies – 60” |

Carnage described in detail. German first aiders bandage Tommies and ‘deliver them carefully to their own people’ |

|

206 |

The growth of the myth of what went wrong |

‘Easier to manufacture a myth of heroic sacrifice than to investigate what had gone wrong under the conditions of modern warfare’. |

|

209 |

The aftermath described |

‘No more villages than a dustheap’. |

|

216 |

Haig’s sanctimonious puffing |

Joffre and Haig |

|

218 |

Before one side cracked |

Liddel-Hart et al, according to Philpott, ‘misconstrued the nature of modern industrial battle’. Foch, as Britain’s ally, maintained pressure ‘in the hope that the rupture at the front would eventually occur’. Such attrition, according to Philpott, had always been a central component of the allied strategy. |

|

227 |

The start of a process that would grind the life out of the German army |

|

|

234 |

Evans’ splenetic tirade |

‘The huge gap between the practical outlook of officers responsible for operations in the field and the gung-ho attitude of those who directed them from the safety of higher headquarters’. ‘They want butchers, not brigadiers’. Griffiths in Hughes. |

|

235 |

False lift copied from French |

Major-General Watts gave his commanders on the ground more discretion over the detail of the operation. |

|

236 |

Hieronymous Bosch (Colin Huges Mametz, 1990) |

‘Years of neglect had turned the wood into a formidable barrier, a mile deep. Heavy shelling had … thrown trees and large branches into a barricade. Equipment, ammunition, rolls of barbed wire, tins of food, gas helmets and rifles were lying about everywhere. There were more corpses than men. Limbs and mutilated trunks, here and there a detached head forming splashes of red against the green leaves, and, as an advertisement for the horror of our way of life and death, and our crucifixion of youth, one tree held in its branches a leg, with its torn flesh hanging down over a spray of leaf … a derelict machine gun propping up the head of an immobile figure in uniform, with a belt of ammunition drooping from the breech into a pile of stained red earth’. Griffiths quotes in Hughes. |

|

237 |

Would pay dividends |

‘Grey-clad corpses outnumbered khaki on the battlefield’ wrote Lieutenant Liddell-Hart … a sight that ‘sight, and contrast, deeply influenced my future military thinking’. Liddell Hart ‘memoirs’. a a crushing military bombardment tactical surprise – a night attack. |

|

241 |

How cavalry was really used |

Compared to vivid imagery and cliché. This cavalry attack, spearing sixteen Germans – charged and cleared the enemy outposts between High and Delville woods. |

|

The mythology of the Somme |

On how it become such a distinct and iconographic event – especially its first day. |

|

|

249 |

Five days crawling around |

Private Raymond Membrey. Memoir. |

|

253 |

Hew Strachan on attrition |

‘the application or acquisition of material superiority’ |

|

Quality of German defence |

Nature of the topography giving the German defence a tactical advantage. |

|

|

263 |

Haig – to his credit |

Had Haig given into French pressure when committing troops before everything was ready on the 1st July 1916? ‘He seemed to be gasping the material basis of industrial battle and was determined not to attack on a large scale until his divisions had adequate artillery support’. |

|

264 |

British ‘learning curve’ – why such an inappropriate metaphor |

‘Such a regular parabola is probably too simplistic a conception to characterise a complex, up and down dynamic’ – it was a developmental process, albeit a jerky and sometimes uncertain one … ‘ |

|

1999 Feature futile ‘The Trench’. Jasper Fforde ‘The Fourth Bear’ |

? |

|

|

CH8 |

Home Fires: Civilians and the Somme |

|

|

295 |

‘The ordinary vulgar exaggeration of the battlefield’ |

Haig critical of The Times and Morning Post concentrating on the French. Press disguised the set backs but couldn’t avoid the lists of dead. The ‘florid tales of daring-do from reporters like William Beech Thomas of the Daily Mail, rang hollow. Brown ‘The Somme’ p.271 |

|

296 |

Massacre of the Accrington Pals |

1st July a date of bitter memory … Equally dreadful for Newfoundland. |

|

299 |

Newfoundland interpretation |

Furnishing the public with a tale of collective bravery and endeavour. |

|

301 |

On filming ‘the Somme’ |

|

|

306 |

Vera Britten ‘Testament of Youth’ |

‘the singularly wasteful and ineffective orgy of slaughter’. p. 276 |

|

311 |

Germany’s film ‘With our heroes on the Somme’ |

Filmed behind the lines and received a lukewarm reception. |

|

314 |

Opinions then and now |

Juxtaposed death and destruction with purpose, courage and derring-do. |

|

359 |

Haig wants to push through three lines |

Rawlinson wanted to take one line at a time, the French way, while Haig wanted to push through all three despite the third line being out of range of the guns. |

|

363 |

use of artillery getting more sophisticated |

Flers-Courcelette Tactical lessons from earlier operations being incorporated into planning and preparation. With more guns and shells the barrage could be twice as concentrated as 1st July. High-explosive shells to cut wire, gas shells for neutralising of enemy artillery, long range indirection fire and creeping shrapnel barrage. |

|

373 |

British tactics were becoming more sophisticated |

Preliminary bombardment, tank, bombing parties, artillery-spotting aircraft … |

|

377 |

Better tactics after three months |

The fall of Thiepval was crushing for the Germans. |

|

380 |

German response showing that Joffre’s attrition was working |

Germany had to develop new defensive tactics. Machine guns hidden in shell holes in Noman’s land. |

|

383 |

Strategic attrition was a chimera |

|

|

384 |

Haig’s battle plans misunderstood |

By September 21 Joffre was feeling that the British army was no longer a weak partner. Haig’s plans were operational schemes, not tactical directives. The commander’s job to think big. |

|

404 |

A push too far by Haig Oct/Nov – or to prevent German defences digging in? |

Despair was setting in for German soldiers. |

|

410 |

Rawlinson against Haig’s desire to keep on the offensive over winter. |

Foch considered fighting on the Somme to be ‘the relief of Verdun of the Eastern Front’. |

|

411 |

Building a sense of their own material skill |

|

|

415-416 |

British improvements in Nov 1916 compared to July |

Pushing the line up the slopes north of the Ancre Consolidating the hold on Redan Ridge Taking Beaucourt. And the first snow fell |

|

417 |

Politicians had little room |

The ‘grinding process’ that was required needed more guns that Lloyd George couldn’t deliver until November. Attrition considered central to defeating Germany. Constraints of coalition, civil-military relations, public opinion and domestic politics. |

|

425 |

Snowballing on the Somme |

|

|

428 |

Kaiser’s peace offer suggested recognition of allied strength. |

|

|

429 |

Success at Verdun thanks to the Somme |

According to Fayolle Nivelle’s successes at Verdun were a ‘consequence of the Somme offensive’. |

|

435 |

Why in Haig’s terms the Somme had worked |

Preventing Germany reinforcing the Russian or Italian fronts. Inspiring a counter offence by the French at Verdun. ‘Manpower is our greatest ally’ The Observer, The War Week by Week. Evening Telegram 3 July 1916. In his despatch of 1st August: Verdun had been relived, German troops had been held in the West and worn down considerably. |

|

443 |

Reduction in fighting capacity of the German Army |

According to Chateris the Germans were not of the same calibre as the year before. |

|

444 |

Understand the Somme July to November 1916 |

The disciplined, confident, conquering army of November 1916 goes less marked tan the self-sacrifice of 1st July. |

|

449 |

Entente terms for peace |

|

|

451 |

Attrition and blockade |

Mandl was depressed at the state of Germany when on leave. |

|

457 |

Australian ‘peaceful penetration’ Jan 1917 |

|

|

460 |

3 hour 1200 yards |

‘Car Wars’ |

|

Germany’s cumbersome ignorance of PR |

||

|

464 |

Haig’s dispatch on attrition |

|

|

473 |

Return to ‘ no more gignotage’ |

Meticulous preparation, |

|

501 |

British trying to mimic the defensive tactics of the Germans |

|

|

514 |

Refinement of tactics – Australian trench raids |

|

|

521 |

Duval knew how to replace men with machines – he knew how to industrialize war. |

1624 light and heavy guns over 1000 aircraft A regiment of self-propelled guns 90 Renault FT17 fast tanks |

|

526 |

Amiens-Mondidier |

|

|

532 |

Drawing in and using up yet more of their diminishing reserve divisions. |

|

|

556 |

Change |

1st August 1932 inauguration of the Thiepval Memorial. The memory of the war as subtly changing. (The pathos, horror and futility of war). |

|

557 |

Michael Howard |

|

|

560 |

Post Imperial jigsaw puzzle |

Poles and Czechs sought to piece together their own states. |

|

561 |

Europe was in a state of Civil War |

Irish Republic, Soviet Union, German, Italy. |

|

569 |

War behind 1920s, war returns 1930s |

Ante-democratic left and right-wing politics. |

|

589 |

The proper application of overwhelming force |

Churchill. Quoted in Terraine p.67 |

|

593 |

How wrong was AJP Taylor and why |

Taylor was imposing himself on the history of the battle. Liberal pacifist political convictions. |

|

595 |

Reshaping memories |

Measured satire of Graves Establishing an image of waste and futility Remembrance reshaped by changing values and the cascading of memory down generations. |

|

596-7 |

Understanding the history of the Somme |

Memoirists trying to reclaim the memory of their war from the politicians, generals and historians whose salvos of self-justifying political and military memoirs had drowned out the voice of the ordinary soldier. |

|

597 |

It was attrition and it worked |

The anti-Somme tends to hold the field as the politicians’ more eloquent voices than the Generals were heard by the British public. |

|

603 |

Robin Prior on the scale, scope and complexity of an attritional war |

Prior ‘World Crisis’ as history Other key components of mass mobilization: relative manpower reserves industrial capacity agricultural productivity resilience of the financial resources |

|

604 |

Haig stuck to the policy of attrition and beating the enemy in the field that Kitchener formulated. |

Blinkered to Lloyd George who wanted to attack against a ‘soft front’. |

|

605 |

An unfavourable force-to-space ratio’ |

Too many men in too little space which allowed the accumulation of strategic reserves behind fixed fronts which negated manoeuvre. Haig and later Churchill provided the men and guns that Haig used to maintain his strategy of attrition. |

|

606 |

An army learning the business of operational command |

Haig was determined and meticulous; perhaps too much so as he interfered with his subordinates … as had Kitchener. |

|

General as professional technicians |

To expect acts of Napoleonic genius is to place them in the wrong age. |

|

|

Communications of the 19th century, weapons of the 20th. |

||

|

608-09 |

Why the British Somme casualties? |

The French had alternative tactics to British methods. Haig too busy scoring points at his ally’s expense to learn from their methods in a way his subordinates were prepared to. The New operational method: coordinated, interconnected and mutually supporting deep attacks Whilst the Somme confirmed that war, warfare itself, had change profoundly, it remained the fundamental strategic truth that military victory, if it were achievable, had to be won against the enemy’s main arum in the principal theatre. |

|

Coalition |

The real events of the coalition battle, and the actual relationship between Foch and Haig, belie the latter’s self-promotion. |

|

|

613 |

Folk memories of WW1 and Blackadder |

Tapping into folk memories |

|

Veterans’ memoir’s ‘glimsped from the bottom a trench’ |

socialist and pacifist collective memory learned experience … |

|

|

614 |

Getting on with the job. Monteith |

|

|

Soldiers as complicators () |

||

|

615 |

Jay Winter on not conflating history and memoir |

Memory cascades down the generations; history is the product of its time. |

|

British strategy becomes stale |

||

|

616 |

Paradigm shift |

Cultural memory versus historic accuracy |

|

617 |

The porous boundary between fact and fiction |

|

|

Western Front Association |

Formed in 1980, now with branches in France, Germany and the US. |

|

|

618 |

Long dead, very often unknown ancestors |

|

|

619 |

Thiepval circuit du souvenir |

|

|

620 |

Sepia-tinted pseudo-past. Their mindset and methods, and misunderstanding their milieu and methods. |

The distorting lenses of memory and history dulled the perception of victory, the purpose of the Somme, if it was not to defeat the German army, was never adequately redefined. |

|

621 |

Vs caricature |

|

|

622 |

A three empire encounter |

|

|

624 |

Those who fought it considered it a success |

|

|

626 |

What went right vs. what went wrong. |

What Haig and Rawlinson contemplated in 1916 was not impossible. Undynamic operational methods stymied offensive battle in 1916 The ensuing long, attritional battle was both anticipated and possessed structure and purpose. Two parts to the Somme: The shock offensive of July and the attritional phases than came afterwards. |

Sir Douglas Haig by J P Harris (2008)

Created in SimpleMinds. get in touch if you’d like a copy. Download the SimpleMinds App for free.

Douglas Haig and the First World War (2008) J P Harriss

Nearly 600 pages that follow a chronology that is familiar. Insights on Haig are limited – perhaps reading Haig’s diary and a biography at the same time would help. This is written by a military historian with judgement of Haig’s command key. We get little insight into the man – if there is much a a personal life to probe. His diary appears to reveal little. What does come over is how often Haig was to blame for actions that were unlikely to succeed in doing much other than expending a good deal of munitions and men – time and time again he planned an offensive that would lead to a break-through, require cavalry support and put tens of thousands of men against barbed wire, machine guns and shrapnel. His greatest skill was to climb and keep climbing the ladder of promotion and to tread carefully around events which might have led to his being passed over for promotion … or his resignation asked for, or accepted.

My first read. A second read possibly to follow unless I can be pointed to a biography.

Notes as iPhone/iPad pictures with annotations (Studio) and a mindmap (SimpleMinds)

Britain had been preparing for war with Germany as is clear from manoeuvres, in this instance with both France and Russia, in 1912 (Harris, 2008:51). Perhaps the re-organisation of the Army to have the Expeditionary Force, however small, was part of an anxiety and vulnerability – had Britain not also contemplated conscription?

As the nature of artillery changed – longer range, great accuracy and a diversity of shells types from high explosives to shrapnel it is staggering that proper thought wasn’t given to how destroyed the land was over which the armies would have to travel.

Typo alert! Actually there are a couple more but I so no value

Where tactics have failed to deliver why did Haig persist? How could more of the same possibly get better results next time? What part of his mindset made him stick to this? Does he lack imagination? He appears emotionally dry or aloof – his relationship with his wife and family hardly suggests a person with a close emotional attachment.

Haig’s greatest skill and purpose was to climb to the top of the Army ladder – what he did or could do when he rose to the top was another matter. This isn’t what makes a great leader – he is like a career civil servant. But what would a hot headed, womanizing, gambler of a man done with this power? If Haig made mistakes they need to be considered and compared with other leaders on the Western and Eastern Fronts. Had Britain a leader like Foch, Neville, Falkenhayn or Holweg … or the Russian aristocrats would we have fared better or differently? And if we’d had Robertson rather than Haig?

History written by a military historian is different to history or biography – the audience here is expected to learn and potentially apply at staff level the lessons from past battles. Haig’s diary is revealing because in this supposedly private moments he is reveals so little: statements of the weather, not what this could mean, statement of events without reflection on what he did well or badly. Self-control in both his public and private life.

To understand Haig then we need to know who the alternatives might have been and whether in reality they could or would have behaved differently: Robertson, Du Can and Rawlinson are different men.

My impression is of a deluded fantasist with no one able or willing to stand up to him … not even Lloyd George. Haig, with Royal patronage and few competing for his role, could and would do as he pleased. He resented having to play second fiddle to the French. In the early stages of the war he ignored orders or requests with potentially dire consequences yet he got away with it.

Haig’s tactics: more munitions, human dynamism and officers of the ‘thruster’ type – people who would risk all regardless. Is there anything we can learn from Haig’s achievements as a polo player from this? What does it require to win at polo?

Haig pressed on with tactics that would leave many thousands dead for little gain and he wasn’t able or willing to question what he could or should do differently.

How clear did failure have to be to get Haig to change his tactics?

Failure of this kind should surely have seen Haig replaced? To what extend did his ‘moral fibre’, his otherwise untarnished character, make it less easy to remove him?

Overexcited, overoptomistic, blind to failure, forever looking beyond the horizon, convinced cavalry had a role, yet able to try gas and tanks … anxious for his peers and superiors to shower him in praise and his subordinates to be fawning …

Self-righteous and self-assured – did his religious beliefs permit his unstinting view of the world? He had the image of someone who deserved authority and respected it. He was fit, sober and in a stable marriage. He worked hard and played the game well. Born into a different age could he have survived? He lacks the flair of Montgomery or Churchill. Described as taciturn, to what degree might or could his asthma have been a controlling influence?

He looked the part and was fastidious about his health – what else could as asthmatic do in the early 20th century? Did he know what the triggers were, or had he learnt from experience to avoid certain foods and situations – not least smoking? Was he prone to chest infections?

Whilst those around him realised all talk of a ‘break-through’ was unrealistic, this is what Haig constantly planned for and expected. Or was it simply wishful thinking?

Step by step is what occurred … as a result from efforts to breakthrough? A case of shoot for the stars and hitting the moon? That in Haig’s eyes step by step would have equated to inconsequential nibbling?

Obsessive, selective, fixated, God-guided, controlling, cavalry-orientated, driven obdurate, blind … consistent, controlled, tempered, magisterial … aloof and with tunnel-vision.

Able to comprehend, but unable to bend? Unable to think of any alternative. The world around him changed, but Haig stayed resolutely in the 19th century.

Chance the way the leaders played off against each other? Men like so many bullets or sandbags, simply a resource to count then stack in the knowledge that there would be great losses but that these could be shored up?

He didn’t like to have his feather’s ruffled. He wanted the game played in his way with him in charge.

A hypocrite who would fail to come to the aid of others … yet others to come to the aid of him. Too good or important to warrant risking his men, or putting his men under another’s control and willing only at the last minute to seek help when things looked desperate and he had no choice.

Related articles

- Haig was no hero (machineguncorps.com)

- Museums watch: The poppy and Reading (getreading.co.uk)

- ‘Your Country Needs You’ (thesocialistway.blogspot.com)

- Alex Massie: War that changed a nation (scotsman.com)

- The First World War Pt.5 (detectingblackpool.wordpress.com)

- Canada and the First World War (anoctoberhorse.wordpress.

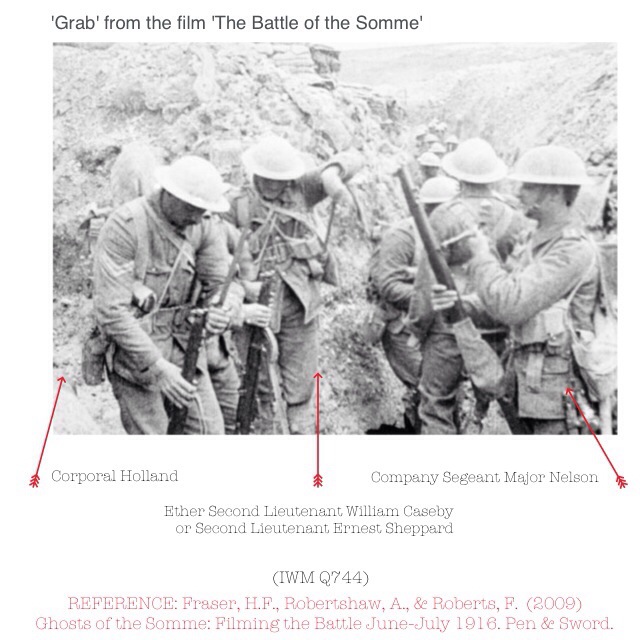

Do you recognise from old family photographs anyone featured in film footage or other archive from the First World War?

I’m looking at ways to engage the public in the wonders of the First World War of a hundred years ago. It strikes me that some of the great grandchildren of the 20 million who saw the film ‘The Battle of the Somme’ in 1916 could be galvanised into helping put names to those featured in these films – who survived, who died – and what was their life story? Short or long?

Sir Douglas Haig’s Great Push

Whilst specialist second hand book shops may from

time to time have specific books or partwork on the First World

War, today one off reprints from digitized catalogues make it

increasingly possible for the amateur hsitorian to research online

then purchase a book that interests them and have it infront of

them in a day or two. It may not have the look or feel of something

that would otherwise be over 90 years old, but its contents are

nonetheless fascinating. Reading a variety of sources has become

like switching channels. In time I have spent writing this I was

able to locate an eBook that ident is som of the combatants and

reer to it directly myself. ‘The Great Push’ makes extensive use of

stills or ‘grabs’ from film footage shot by Geoffrey Malins of the

Battle of the Somme. Partworks such as these fed an understandable

hunger for insight and news, whilst the hidden agenda of seeking

support for the conflict and its justification is obvious from the

ebullient language. With 50th, 90th and now the 100th anniversary

if these events upon us new generations of historians and amateur

sleuths are able to add yet more to the images, both still and

moving, that were captured at the time. As well as revisiting and

identifying the spot where a picture was taken, every effort is

made to identify any of those featured in the pictures. With the

power of tens of thousands via the Internet it is reasomable to

believe, that even 95 or more years on that yet more combatants

will be named and in so doing, as the relevant archives are so

readily available, to say who more of these people are – where they

were born and went to school, where they worked and where they

joined up, what service they have seen to date and how the war pans

out for them. The national habit has been to remember those who

died in combat, but of course all are now dead and the opportunity

therefore exists to remember a generation, not only those who took

a direct part, but those on ‘the home front’ who faced their own

trials and tribulations. I believe it is in this spirit that the

BBC is marking the events of 100 years ago.

Keep died on the 17th July 1917 in the Ypres,

Salient. He was 24. As we can identify him, we can surely provide the names of his platoon and in doing so might others look through newspapers as well as their own family photographs to see if more names can bedpntdtocfacesc97 or more years after the event?

Not only do you often come across images taken from the film ‘The Battle of the Somme’ that make false claims to their content, but authors try to confer their copyright to the material. Whilst it was common practice of the times to quite crudely add black or white highlights to a photograph in an attempt to improve clarity. In an era of Photoshop these efforts look clunky.

How Geoffrey Malins filmed episodes of the First World War

My immediate thought here is that over 100 years

My immediate thought here is that over 100 years

capturing events such as this have gone full circle – we are back

to one person and his kit trying to see the action. It also strikes

me as someone who is so familiar with activity on the Western Front

and action in the trenches that he misses much of the key action:

he cannot film at night, nor can he get in amongst the action, nor

of course is there any sound. Colour adds clarity as you can

differentiate more of the detail. In any one day at the end of June

and early July, the months that interest me, how much did his

cameras see? An hour one morning, a couple the following afternoon?

It is worth thinking how much wad going on when he was mot turning

the film through the camera. The kit was cumbersome and heavy. It

weighed 5 stone. Then there were cannisters of film he strung

around his neck. He has a canny turn of phrase. He describes the

Howitzers he films as a ‘horrible frog squatting on its haunches’.

p120. I wonder if the cameraman has as much of a story to tell

given the difficulties and dangers he must face getting into

position. There are many times when he describes what he hadn’t the

means to record: the frying bacon, the boiling water, the chat

between soldiers … laughing, swaering and humming songs. p132

What does war really mean? Is this a question such filmmaking hoped

to answer. There appears to be a niavety about the entire

enterprise.

I’m familiar with The Battle of the Somme footage so am delighted that it is brought to life by Malins’s words describing people and events before, during and after his bouts of filming. The dressing station sounds far more horrific than he feels. He must surely have fekt sensitive about filming people as they died.

Souvenirs

I remember being in the brick factory on the Somme at Trones Wood. There was this huge crater, this was in 1916. I was trying to boil some water. I’d set up a bit of a fire with a couple of bricks and a canteen. The smell was dreadful. So I pushed my bayonet in and there’s a dead body.

When they started the war Jerry had those helmets with a brass peak. One day I saw this spike sticking out of the side of this communications trench and I thought it would make a nice souvenir and I got my bayonet out and dug the earth away to get hold of it. My fingers came away with skin and hair and all the rest of it. It was a dead German.

I got one in the end.

They Called it Paschendaele

For an insight into the life, death and frontline tactics along the Western Front controlled by British and Commonwealth troops you should begin with Lyn Macdonald’s ‘They Called it Paschendaele’. First published in 1978 it draws on interviews with some 600 veterans. I return to it often to expand on the record I got directly from my late grandfather John Arthur ‘Jack’ Wilson M.M. who was a corporal in the Machine Gun Corps, serving in Neuve Chapelle, Arras, the Somme and then Ypres between April 1916 and December 1917 when he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps and trained to be a fighter pilot.

In 1991 he visited the Imperial War Museum where he was able to sit behind a Vicker’s Machine Gun, then the following year he visited Ypres for the 75th Anniversary – a guest of Lyn Macdonald.

More at http://www.machineguncorps.com

The most iconic image from the 1916 film of the Battle of the Somme

The big push on the big screen of picture theatres across Great Britain in 1916

http://greatwarlondon.wordpress.com/2012/08/24/the-big-push-on-the-big-screen/