Home » 1917

Category Archives: 1917

Rottingdean’s Great War

This morning I received a delightful surprise as glimpses of sun broke through the heavy winter grey and old Rottingdean revealed itself around its war memorial and pond. I parked next to the war memorial with its Roll of Honour to both wars, with Rudyard Kipling’s home of five years behind off the green – somewhere he abandoned as it became a popular destination for tourists seeking him out.

A short walk took me onto the South Downs behind Saltdean – a walk that could be greatly extended when doubling back you see to the sea, the iconic old windmill on the hill and in contrast the vastness of the massive Rampion Offshore Wind Farm on the Channel horizon.

The return through the edges of the town showed off the many bedroomed ‘executive homes’ of the last century with their Jags and Range-Rovers, as well as the apparently older properties along Tudor Close by the church and cemetery which turn out to be cottages created out of the 1920s Tudor Cottages Hotel. The Manor House dates back to the 15th century, the Black Horse pub to the 16th century whilst The Elms where Kipling lived is 18th century and the Grange and North End House (where Burn Jones lived and worked) are 19th century.

Much occurred in the late 19th century with Burn Jones and Rudyard Kipling residents and the boarding prep-school St.Aubyns which saw many of its students graduate to the likes of Eton.

My First World War interest saw me visit the exterior of the school (closed for five years and being developed into apartments and houses). Its abandoned and trashed interior can be seen online courtesy of an old boy who broke in a few years ago to take a look. The journalist, author and Scots Guards subaltern Wilfred Ewart was here 1900-1905 as was his friend George Wyndham.

My First World War interest also took me into the churchyard of the quirky St Margaret’s of Antioch with its nativity display still out in late January.

I spotted a dozen or so CWGC graves, mostly the class Portland stone, some private memorials. These include:

| Fireman H Bateman, died 20 May 1917 on the SS Tycho. Mercantile Marine. Steamer sunk by a U Boat off Beachy Head. Body recovered and buried here. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| 267153 Pte William H Chatfield, Royal Sussex Regimentand 458331 Labour Corps died 14 February 1919 ‘of sickness’ (age 20) Son of Mr and Mrs Herbert Chatfield of 9, The High Street, Rottingdean. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| 2nd Lieut. David Dennys Fowler, RFC Born 20 June 1897, Seawall, Glenelg, South Australia Son of James Fowler of Dyxcroft, Rottingdean and and Mary Harriet (née Morgan), both were born in south Australia. In 1898 David’s six year old brother died. At some point in the next year or so the family moved to England. 1901 Albert Gate, Knightsbridge with his parents. His father was a ‘merchant grocer’ (employer) from south Australia. In 1909 a younger brother James was born (the family was by then living in Surrey). At the 1911 Census, Dennys, age 13, as he is known, was at school, Wavetree House, Furze Hill, Hove, Brighton, the census sheet showing 20 boys ages 12 to 13, of whom two were born in India, and Dennys in Australia. He then went to Harrow, was part of the OTC, leaving in December 1914. Although war had broken out to he took up at place at Trinity College, Cambridge. He had only just matriculated when his mother died on 14 November 1915 in Wimbledon. On 13 January 1916 he applied to become a flying officer. He gained his Aero Certificate in a Maurice Farman Biplane 29 May 1916 at Military School, Catterick Bridge. Second Lieutenant David Dennys Fowler reported from England and posted to No. 1 Squadron, A.F.C. (Australian Flying Corps), at Heliopolis on 4th September, 1916. Fowler was wounded on 5 October when his BE2c was hit by anti-aircraft fire while on reconnaissance with 2Lt J Hutchins as his observer, who escaped unhurt, but Fowler was sent to hospital in Tigne, Malta on 5 October 1916 with gsw to left foot. In December 1916 he was invalided back to England and attached to No. 78 Squadron, R.F.C. Text supplied by Chas Schaedel and the South Australian Aviation Museum History Group On the night of 17 March 1917 he was flying a B.E.2s Serial number 7181 on a Zeppelin patrol after an air raid. He was turning too near to the ground, causing the left wing tip to touch and the plane crashed about one and a half miles from Telscombe Cliffs Aerodrome and was killed. https://ww1austburialsuk.weebly.com/rottingdean.html He was buried in St.Margaret’s of Antioch Church, Rottingdean on 20 March 1917. Grave inscription: In His Twentieth Year With Every Promise Of Happiness Before Him He Gave His Life To His Country Sources: Australian Birth Index; UK, Soldiers Died in the Great War, 1914-1919; British World War I Medal Records. Died in Salonika; England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995; Great Britain, Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificates, 1910-1950; 1901 England Census; The Street of Brighton and Hove; Virtual War Memorial, Australia. |

| Image to add |

| 67450 Pte Reginald W King, The Labour Corps formerly formerly G/3064 with Royal Sussex Regiment died at home 3 November 1918 (age 32) Son of Henry and Lottie King of 29, Quebec Street, Brighton. Husband of Mrs Daisy King of 2, Rifle Butt Road, Rottingdean. |

| Lieut. William Oliver Redman-King (special list) Born in Brighton. Died of pneumonia at home 28 February 1919. Son of Dr. J. B. and Mrs Annie Louise Redman–King of Weetwood Hall, Leeds, Yorkshire. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| Image to add |

| Serg.Maj. J H Rose, RFC, died 28 January 1916 |

| Image to add |

| Maj. Cuthbert R Rowden RAF/Worcestershire Regiment 78th Sqdn. Formerly with the 5th Worcesters. Died at home 20 April 1918 (age 21) Son of Arthur Roger and Blanche Mary Rowden of Eastnor, Ledbury, Herefordshire. Husband of Mrs Frances Rowden of ‘Halcyon’, Redhill, Surrey. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). |

| Fire Engineer J Short, Mercantile Marine S S Tycho died 20 May 1917. When the steamer was sunk by a U-boat off Beachy Head. Body recovered and buried here. (Initial detail from the headstone and the Roll of Honour compiled by Chris Comber). A ninth unnamed WWI Mercantile Marine is also remembered here. |

I’ll return to Rottingdean to seek out the graves I failed to spot this time round. I will also slowly complete short profiles for each man who served and died. My starting place will be the Roll of honour for the Rottingdean War Memorial produced by Chris Comber in 2004. Where I can find a photograph of the person being remembered and a Pension Card and further family and service details I will feature these in a commemorative post to the ‘Remember on this Day’ pages of The Western Front Association.

One’s first impression of the First World War should be the right one

Fig. 1. All Quiet on the Western Front

A student’s first impression of the First World War should be the right one.

Life was largely spent out of the trenches rather than in: on field marches, labouring, resting, training … or filling the time out of boredom. I only recently came across ‘Tartans’ – detailed charts showing week by week where a battalion were … for many it was months out of the line then a week or two in and out of the line.

Blackadder cannot and does not get close to ‘living’ in a trench: the constant threat of death, atrocious conditions, friends being injured and dying horrible deaths. Soldiers learnt and knew the sound of every kind of shell going over to fill the time. And whilst communications with High Command could not be direct there is a largely excellent rapport between infantry and officers.

Nor were the only ‘posh’ public school idiots. Many staffers applied for and get commissions in the trenches – begged for it. Yes, the five minutes of the last episode are moving, better though to show ‘For King and Country’, or ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ …. even ‘Johnny Got his Gun’ or the extraordinary Metallica video and rock song to that film. I hope ‘Testament of Youth’ does the job.

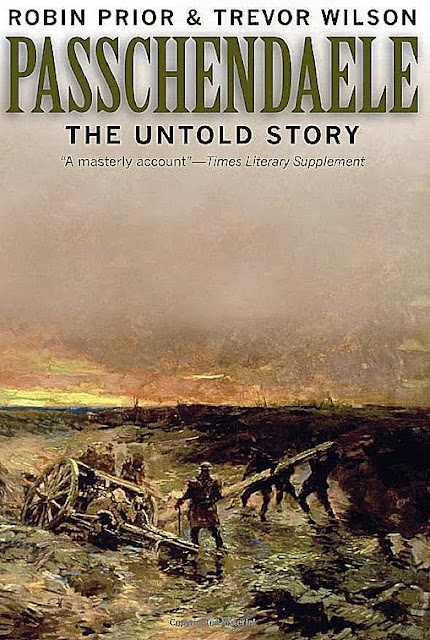

Understand Passchendaele to understand Britain in the First World War

Like a disease my books on the First World War have more than quadrupled; you take the subject seriously (MA) and now I need six texts on everything. My current task, almost complete, is to understand what the f*ck went on during Third Ypres (Passchendaele). And now I know, largely due to this book: Passchendaele. The Untold Story (1996) Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson. When I’m told and go and explain what was going on to my grandfather, now approaching 118 and in an urn in the shed. Actually, as a machine gunner he was less likely to get killed or injured that the soldiers ‘going over the top’ – in some instances 50%, 70% even 80% of those being sent in became casualties all because … because our government i.e; Lloyd George had gone from hands on interference to letting the military get on with it, because Haig was the archetypal public school boy over promoted dim wit whose greatest skill was riding a horse and currying favour from those above and at his side. The evidence makes me angry. He could have and should have been removed, indeed, refreshing your military leaders, as France did, was probably a good idea.

A month in Passchendaele – October 1917.

I’m giving a presentation on it on June 14th. Somehow my irritation and anger needs to subside into something more objective over the next month. It is NOT revisionist to curse the British military leader who, for all the evidence, expected tens of thousands of men (not all young, my grandfather served with a bloke of 42) to fight, despite everything that he was told and knew of how futile it would be, through the quagmire of the Ypres Salient. Haig allowed value judgements and private passions to supersede common sense … and by then blunt experience and evidence of repeated failure.

A week in the Ypres Salient

My grandfather was sent in to relieve a couple of fellow machine gunners on the 19th of October 1917. Columbo House. He went in a couple of times. Also Nobles Farm. This is south of Houthulst Forest during the final efforts to take the Passchendaele ridge. Getting to this part of the line could take many hours, in the dark, at considerable risk of slipping off the duckboards into deep, unforgiving shell-holes full of mud and water, body parts, blood and chemicals from gas shells. I have the local. I haven’t quite got the dates, but he was with machine gunner Dick Piper when he died of a stomach wound and had already buried the ammunition carrier Henry Gartenfeld – a married man with two kids in his early forties by the way. My grandfather always expressed his dismay that the man had got in, that the war should have been for unmarried men with no attachments. He had none. Or he kept quiet about it.

My impressions of what he went through ‘keeping the gun in action’ for a week, without relief, for a week have changed over 46 years. What I saw in my mind’s eye when I was five or six, cannot be the same as what I perceived when I was ten, or twenty or even thirty years older. As well as his own two men, dead or dying there were, some twenty Guards lying behind a wall next to this pill-box. All dead beat, or dead, or dying. Mostly gassed he reckoned. From some push into Houthulst Forest that had gone wrong. No forest of course, just the dissemination and wreckage as if a hurricane had swept back and forth over several weeks reducing the trees to stumps and sticks. Aerial photographs show a pockmarked land with handfuls of snapped matched sticks and on the ground or in the shell holes lice-like bobbles and impressions – dead men litter the landscape like eggs from a careless spider.

This is the view that Flight Lieutenant William Wilson would have had … my grandfather’s younger brother, who at 17 had joined the RFC and in 1917 was flying De Haviland bombers’ over the German lines to try and wreck railway lines.

Haig … and Lloyd George

My first impression was bad, my second impression good, my growing view is not only on the bad, but anger that those who should have pulled Haig from the job, Lloyd George, did not do so. Though Haig and Lloyd George loathed each other they had something in common – they both carried on, in their own way, a merry little dance that was designed primarily to keep themselves in power and their reputations clean. All in power have to be accountable to others in a way that means they can be asked to account for their actions and record and where it is found to be failing they are swiftly replaced.

Why the BBC series ‘The Great War’ (1964) has not withstood the test of time.

Fig.1 Freeze frame from the ‘Great War’ title sequence

The Great War’ television history series produced by the BBC in the early 1960s has not stood the test of time and so does not warrant broadcast 50 years on. I can give four reasons why it is dated; 1) as an artefact; 2) because of the social context in which the BBC produced and transmitted the series fifty years ago and, 3) how it compares to series produced to mark subsequent commemorative First World War milestones and 4) coverage planned by the BBC for the period 2013-19.

If ‘the work of the historian closely mirrors the society in which he works’ (Carr, 1991) the ‘The Great War’ needs to be seen in the context of the early 1960s when there was an outburst of publications as well as radio, TV and theatre on the First World War. Whilst ‘The Great War’, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the First World War, stood out for the reception it received and audience sizes it should not be seen in isolation.

The BBC producer, Tony Essex, who conceived of and produced ‘The Great War’, was not an historian, but a hands-on filmmaker. (Hanna 2002:02) He devised the thematic approach of ‘The Great War’ and demanded a literary style from its writer (Hanna 2002:35). He saw the series as an epic tragedy, a story ‘as great as that of the Bible. (Hanna 2002:38). He personally ensured the inclusion of ‘the war poets’ even suggesting that a poem commissioned from Siegfried Sassoon would feature in the opening sequence of every episode (Hanna 2002:36). As a ‘creative’ producer his intentions are most clear in Episode 17, where ‘Passchendaele’ is told as a horror story with music that would be fitting in a Hitchcock thriller while the narration describes the hideousness of the worst nightmare – being wounded and slipping off the duckboards to drown in the mud. This is the tragic story that Essex wished to tell; the emotional appeal too strong for a reasoned and object history. The few seconds that is the title sequence, was designed by the producer to be an ‘Alice in Wonderland-like’ tumble down a rabbit hole that lands you on a snarling skull attached to a flesh and cloth tattered body is evocative of what follows, Hanna (2002 pp.38-45). For viewers in 1964, Essex preached to the converted, fuelling the view that the war was a futile waste of young heroic lives. Essex aimed to ‘proselytize, if not instruct’. Hanna (2002:32) writes that the visual and emotional impact carried by the images ‘cemented … war myths already embedded in Britain’s cultural landscape’, something that greatly frustrated the lead writer John Terraine as, overwhelmed by the film’s images and music, audiences missed his revisionist views of Haig and his interpretation of the Somme and Passchendaele as an historian. John Terraine was the lead writer who wrote thirteen of the 26 episodes and co-wrote another two. Keegan (1978 pp. 664-5) describes Terraine as ‘the Enoch Powell of British Military Historians’. The historical adviser Liddell Hart fell out with Terraine and quit the series., Hanna (2002:32) Liddell Hart published his complaints in an open letter in The Times disagreeing with how Terraine portrayed Haig and wrote about the Somme and Passchendaele. Strachan (1991 pp. 41-67) While Danchev states that Terraine is the author of a ‘prevailing orthodoxy’ (Strachan, 1991). Perhaps Correlli Barnett, one of the writers on ‘The Great War’, was right when he said that ‘television history is too superficial and ‘précised’ to be anything other than popularisation.’ Barnett (2006:7)

John Terraine said that writing for TV was different to writing history for print (Hanna 2002:51). Television, especially as broadcast in the early 1960s in Britain was to sit down to view a passing event (Moran, 2013). This rarity helped lodge it in the national psyche. Television is no longer like that.

According to Grieves (2002), Terraine drew largely on the official histories and quasi-official memoirs and according to Hew Strachan, Terraine only saw the war in terms of a ‘westerner.’ For a western audience then, and a British one, in 1964, the lessons and experiences of ‘The Great War’ as expressed satisfied the prevailing beliefs; these would not satisfy the views of a British audience in 2014 that is better educated, increasingly professional and multi-cultural.

It is the interplay of images, music and words that delivers the ‘epic tragedy’ that Essex desired, the impression left with viewers not always that desired by the writers. In Episode 9, whatever John Terraine wanted to say in revisionist terms about Haig fighting a war of attrition, the ‘literary’ prose dramatized by the narration of Sir Michael Redgrave and backed by music composed by Wilfred Josephs that sounds like a pastiche of Samuel Barber’s ‘Adagio for strings Op. 11 leaves viewers with this sense of ‘futility and loss’ (Hanna, 2002:7) – the overwhelming feelings experienced by audiences. For an historical perspective, although ideas such as ‘Britain’s new army was growing old and wise in battle’, (Disc 4) were well grounded, the choice of images from the archive footage that the production team were limited to, made it are hard idea either to show, or to convince others of, for this different production techniques and approaches would be required, for example the conflicting views of historians openly debated, something future programmes on the First World War would do. Only through pausing and replaying a DVD can you wonder about such lines as these: ‘Every citizen fought his private war of independence when he decided to uproot from Europe’, which rather ignores the population that was already there, or African-Americans who had been taken there as slaves; or how to stirring and patriotic Elgar-like music we learn of the role of the US ‘Making the world safe for democracy’ and ‘Fighting for the Anglo-Saxon race to save the world.’ In 1964 the cold war threatened the world, and such lines would be evocative for audiences then, that they could be in 2014.

In 2014 the audience, not the press are the ‘produsers’ – (Bruns, 2006) they both ‘produce’ and ‘use’ digital media; they are the reviewers and where they find fault or points of contention they will stop, review, scrutinise, compose their thoughts and share online. If broadcast ‘The Great War’ would generate considerable debate though it is doubtful that viewers would conclude, with the exception of A.A. Gill and his Sunday Times readers, that it has ‘stood the test of time’. A.A.Gill is critical of anything on the First World War that is not ‘The Great War’. (Hanna, 2002:55) For the fiftieth anniversary of the First World War, as for subsequent anniversaries of note, ‘The Great War’ was commissioned as public commemoration on Britain’s public service TV channel – it also made history as a piece of programme making. (Hanna, 2002:10) Four component parts equate to the experience of viewers fifty years ago: the words, the images, the music and where viewed.

The words, spoken and brought to life by benighted British Thespians such as Sir Michael Redgrave give it an ‘establishment’ tone worthy of a sermon from the pulpit. The audience are supposed to listen and not question the facts or the views. These words are evocative of a different era. The words jar to modern ears, for example, in Episode 13, Terraine wrote:’ ‘The British regiments marched to catastrophe. These were Lord Kitchener’s volunteers. The eager, enthusiastic, physical, spiritual elite of the British race.’ While in Episode 15, Gordon Watkins and John Williams wrote: ‘The Senegalese, their chocolate faces grey with cold, were unable even to load their rifles. Caught between German artillery and their own fire they fled the field.’ And in Episode 16, Alistair Horn writes of: ‘Fighting for the Anglo-Saxon Race to save the world”. While in Episode 22, the soundtrack features bombastic trumpets as the bombardment starts ahead of the Americans going in with John Terraine’s words ‘A blood transfusion on a scale never dreamt of now began’.

These are words narrated by actors, not delivered by broadcasters or from the mouth of a subject matter expert. Where there are interviews some of the participants appear to have been schooled or to have learnt their lines; effort by some is made to speak in a Reithian ‘BBC English’. Over the last fifty years regional accents have been celebrated and authenticity in interviews, especially in documentaries or news reporting, managed and edited so as not to suggest any tampering with the words spoken or opinions expressed.

The images were limited to those from the era – indicating why so little is said on the Royal Flying Corps, as there was little to show. (Hanna, 2002:47) This may also suggest why so little is said about the soldiers as conscripts rather than volunteers – they made up 50.3% of the British Expeditionary Force. (Hanna, 2002:48) Finding footage to fill nearly seventeen hours resulted in compromise – the producer is left being unable to say what cannot be illustrated. Episode One, for example, suffers from either starting or indulging the view that Europe was basking in a tranquil summer – the calm before the storm. Since 1964 the techniques for historical documentary making have developed so that greater credence can be given to the history. The BBC co-production 1914-18, (Hanna, 2002:54) transmitted in 1989, had a panel of historians advising and writing for a shorter series that is Euro-centric and puts the conflict in context in a more objective, informed and open manner. It’s approach that shows how the history documentary genre has moved on, especially having international markets for the programme in mind and so implying that ‘The Great War’ has not stood the test of time. In Episode 19, we are shown a curiously drawn Map of the world that self-evidently gives more significance to some countries and less to others … a dubious representation of the actual geographical the world as the narrator reads while the narrator reads ‘It was a world war now, few countries of any stature were able to stand aside’. Such views would jar with a British audience in 2014. Some subsequent TV productions have done worse, for example, ‘World War One in Colour’, (Hanna, 2002:56) but ‘The Great War’ used footage shot to cover the Somme in 1916 to illustrate events across the period 1914-18. For editorial reasons ‘The Great War’ says nothing of the Armenian genocide and glosses over the French Mutiny, by doing so the orientation taken by Essex is clearly a British perspective.

As an historic artefact ‘The Great War’ was corrupted by the production process. For example, footage shot to cover the Battle of the Somme, from soldiers going into the trenches, to the wounded returning and prisoners of war, is used repeatedly to illustrate the events of 1914–18 not just of 1916 – an approach that would be considered unprofessional today and open to criticism. Filming was limited by access to the action and tainted as the authorities banned, then permitted, then censored the content that was processed, edited and distributed to cinemas. (Fraser et al. 2009) Here we enter the debate of history as truth against reflecting the views of its authors and the age, even to the worthiness of history on TV. Corelli Barnett argues that presenting the stories to millions via the TV medium is a worthwhile compromise. (Fraser et al. 2009) The music, composed by Wilfred Josephs, (Hannah, 2002:38) evoke specific emotions as one would with a drama series is often overpowering, much to Terraine’s frustration it was a combination of the images and the music that people recalled which left an impression not of a necessary endeavour, but of a futile and horrific waste of life. (Hanna, 2002:51) Music supporting the moving image controls and influences mood. In ‘The Great War’ consideration of the opening title sequence alone and its impact on audiences indicates what impact it can have. Wilfred Josephs composed music is gut wrenchingly sad, fully of tragedy, horror and drama. He went on to compose for TV drama series such as ‘The Prisoner; and ‘I, Claudius’. Throughout the 26 episodes of ‘The Great War’ the images and music play off against each other in way that is far closer than that achieved by the words as the composer worked to the edited images, whereas the writers, under instructions from Essex, were kept from looking at any of the rushes chosen from the era in order to write to his demanding literary standard. (Hanna, 2002:52) As a televisual experience this is a compelling attraction of ‘The Great War’ as a piece of emotional storytelling and for this reason some would say it has ‘stood the test of time’. The impact from the choice of images and demanding music was greater than that of the words. (Hanna, 2002:35)

The sitting room was part of the experience – a tiny screen (by today’s standards) showing a fuzzy black and white image in the corner of the room, the curtain closed, the family gather to watch together with Mum knitting and the kids look up from the floor. (Moran, 2006) The technological changes to the way TV is viewed in Britain 1964-2014 significantly impacts on whether ‘The Great War’ has stood the test of time. Is Charlie Chaplin still broadcast? In Britain, in 1964 there were two channels delivering 425 UHF or 650 VHF black and white analogue set, while in 2014 we enjoy multiple digital HD and 3D channels viewed when we like on a multitude of large or small screen static or portable devices that are linked to the Web.

‘The Great War’ set in motion a great swathe of subsequent BBC productions, from Alan Clarke’s ‘Civilization’ (1968) to David Attenborough’s ‘Life on Earth’ (1972) and Jeremy Isaacs ‘World at War’ (1974), (Hanna, 2002:52) but this is why it is difficult to view outside its historic context – it is not as a piece of programming that would be palatable to a contemporary audiences because of its dated production techniques, its preachy and overly dramatized story telling and at times its inaccurate, Anglo-centric point of view.

Both BBC radio and TV had in different ways looked at the events of the First World War. A J P Taylor had delivered a series of radio and TV lectures. (Hanna, 2002 pp. 17-18) On BBC radio ‘The long, long tail’ used popular songs of the 1914-1918 era, re-versioned for the stage as ‘Oh What a lovely war’ that in turn became an enduring movie.

Britain was still a colonial, if not a global power. Baby boomers were growing up. TV was still a British, even an English dominated medium, whereas cinema had long been taken over by Hollywood and the US. The class divide of the British population is immediately apparent in the Great War TV Series owing to the use of actors as narrator and voices of prominent First World war figures – there is an onus on ‘received pronunciation’ and ‘the Queen’s English’, even those interviewed speak in a clipped, scripted way with regional accents so watered down they are almost indistinguishable – the early 1960s was an era when the working class took elocution lessons if they wished to ‘rise above their station’ – to call upon a phrase of the First World War generation.

In 1961 only 19% of the population were in professional or managerial and technical jobs, whereas by 2011 this has increased to 49%. In 1964 there were over 100,000 veterans in their early 70s and 80s as well as a larger population that had lived through 1914-1918. The audience in 2014 is different because it is better educated and wealthier. Their views are different and less divided by class. In 1964 there was however a prevailing orthodoxy. (Danchev 2002:273) The audience for ‘The Great War’ was captive and predisposed to the interpretation.

A documentary series of this scale was new to British Television; the format of ‘celebrity’ subject matter expert delivering in situ to camera and conducting the interviews was yet to establish itself, drama–reconstruction was frowned upon – old and established formats still reigned, for an example, with the transmission of a series of history lectures by A.J.P. Taylor. (Hanna, 200 pp. 17-18) The skill of scriptwriting documentary for a visual medium came from cinema and the newsreel. The Great War reflects a transition between the newsreel and the narrative documentary. (Hammond and Williams, 2011)

The 1960s is not reflected in the ‘The Great War’. This was a decade of increasing antiestablishmentarianism, where the generation of ‘baby boomers’ began to assert themselves in programmes such as ‘The Week that Was’. Views of the First World War fell into four camps: respect, derision, attempts at objective interpretation that could only be fully informed by with the release of official First World War papers between 1968 and 1972, (Danchev, 2006:270) and opinion that ranged from the bias of a Marxist-Leninist view to fictionalised, largely anti war storytelling such as ‘King and Country’ and ‘Oh, What a Lovely War’.

Respect and a received point of view, inevitably came from official points of view of the war, the historical record had been written by the ‘victors’ in Soviet Russia, the French Republic and a Great Britain whose empire was in tact between the wars but described as ‘fizzling out’ by the 1960s while Germany still struggled to assess objectively both the execution and outcome of the First War and its role in leading to the Second.

Thirty years on from ‘The Great War’ the BBC marked the 80th anniversary of the conflict with a re-versioned US series 1914-18. Without bombast, shock or sensationalism this series, though there have to be gaps and précis, took a gentler, more nuanced and considered view of events including episodes that ‘The Great War’ missed, from the Armenian genocide to the experience of African troops, to the role of women and close analysis of the personae dramatis of the French mutiny. The debate about Haig is introduced but not tackle and new themes are introduced, such as the role of national honour to fuel the war.

The choices made are considered and the product of working with a panel of historians with different specialism. It may gloss over the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, but profile of the Kaiser Wilhelm II closely while the debate regarding Haig is stated as such and then left. We gain the Armenian genocide, the role of women with profiles of Vera Britten, an American nurse and munitions workers in Britain, but there is still, as in previous television series, little on the ‘war in the air’ no doubt for want of suitable footage showing how the images may still dictate the stories that are told. The poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen are closely scrutinized and there is greater social, political and cultural history. It is a ‘people’s story’ with the profiles of the likes of Jean Jaurès preferred over the leaders covered in previous histories. The inclusion of the African story is refreshing.

We don’t watch TV the way we did in 1964, this is reflected in the planned output by the BBC to mark the 100th anniversary of the First World War: every kind of genre, across platforms, for audiences from nursery school to Newsnight via Children’s BBC (CBBC) and the Open University (OU) with 2,300 hours of TV, Radio and Online content.

In many different ways, this addresses the issues and events comprehensively for distinct audiences rather than the family that would have been expected to sit down and view ‘The Great War’ in 1964.

Historians are ‘people of their time’. (Evans, 1997 pp. 257-261) The 2,300 hours of TV and Radio output from the BBC between 2013 and 2019 will reflect the way in which multiple voices, and in particular the voice of the viewer is heard. There is no more significant pointer to the character of a society than the kind of history it rights or fails to write (Carr (1991:43).

‘The Great War’ is best seen as an artefact, of historic interest for what it is. Indeed, UNESCO accepted ‘The Battle of the Somme’ documentary footage shot in 1916, into its Memory of the World register in 2005 (UNESCO, 2005) – the rushes of which feature throughout ‘The Great War’. In turn ‘The Great War’, created from 844,800 feet of archive footage and over 20,000 photographs, paintings, posters and contemporary newspapers from twenty countries and compiled by 33 staff. Viewing the ‘Great War TV series’ in 2014 would best be achieved in bite sized form on YouTube on a handheld device, picking selective moments to suit the time and place – perhaps contemplating the sacrifice of soldiers in front of a memorial to the dead or on a battlefield ‘pilgrimage’. The audience, without any living experience of the events, will view it through the lens of subsequent and current wars and how these are reported. They will, by choice, or prompted to do so, form an opinion by drawing on multiple alternative sources and most significantly ‘sit forward’ to share and form views on social platforms rather than taking the views of the original authors as gospel.

A television series is different to the printed word yet the temptation is to compare ‘The Great War’ to individually authored histories, part works or other ‘epic’ volumes on the events or encyclopaedic official histories. The challenge in 2014 and pertinent to the question of whether ‘The Great War’ has stood the test of time is how technology, especially digital formats on large screens and in our pockets, that allows instant sharing, feedback, and meaning construction through networking. If, as Marshall McLuhan (1962:8) suggested ‘technology extended senses’ then the technology we hold, pocket and wear today, are a prosthesis to our senses and to the manner in which the product of these senses is stored, labelled, interpreted, shared, re-lived, and reflected upon. For this reason ‘The Great War’, if its authors, and the owners of the copyrighted footage wish to galvanise and interest a 21st century audience, it should be posted online as an open education resource.

In 2001 Badsley spoke of ‘two Western Fronts: the Western Front of literature and the popular culture and the Western Front of History’. Badsey (2001)

In 2013 we have multiple Western Fronts because of the Internet and Web 2.0 where the individual, with a second screen, sitting forward, creates, shares, and in the context of the First World War exploits what Sobchack 2002 described as ‘mediaophemes’ – a bite sized nugget of impression and meaning that renders itself easy to view, post, mash-up, comment on and share.

Though ‘The Great War’ has not stood the test of time, it nonetheless set in train the development of the television history series. Ironically, with the advent of YouTube, the kind of lecturer that A J P Taylor gave in the 1950s and 1960s on radio then TV is exactly what is suited to the Web as a TED lecture. Other transformative platforms online include discussions around book reviews on Amazon and the massive expansion of family history. (Dixon and Porter, 2001)

To view the series an unopened DVD box set from 2002 will cost around £100 through Amazon. Instead go to the BBC World War One Centenary website and plan you listening, viewing and reading over the next five years.

REFERENCES

Badsey, S. (2001) ‘Blackadder Goes Forth and the Two Western Fronts Debate’, in G. Roberts and P.M. Taylor (eds), The Historian, Television and Television History. Luton University Press (2001)

Barnett, C. (2006) ‘John Terraine and Television History’, Stand To!, 2006 75 PP. 7-8

BBC ‘The Great War’ (1964) Special Edition 6 Disc Boxset. (Simply Home Entertainment 2009).

BBC, The Great War (1964) Special Edition 6 Disc Boxset. (Simply Home Entertainment 2009) Disc four. Episode 17 ‘Surely we have perished’ by John Terraine.

Bruns, A. and Jacobs, J. Use of Blogs. (Peter Lang Publishing. 2006)

Carr, E.H. (1990) What is history? (Penguin History 1990 [1961])

Danchev, A. (2002) ‘Bunking’ and Debunking: The Controversies of the 1960s in B. Bond, B ed., The First World War and British Military History. (Reprinted hardback edition, Clarendon Press Oxford: 2002) pp. 263-288

Dixon, B and Porter, L (2011) ‘‘How Shall We Look Again’? Revisiting the Archive in British Silent Film and the Great War’, in D, Porter and H. Williams. (eds) British Silent Cinema and the Great War. (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011)

Evans, R.J. (1997) ‘The History of History’ in ‘In Defense of History’ (Granta Books, 1997)

Fraser, A.H., Robertshaw, A and Roberts, S. (2009) ‘Ghosts on the Somme. Filming the Battle, June-July 1916 (Pen & Sword, eBook, 2009)

Grieves, K. (2002) ‘Early Historical Responses to the Great War: Foretescue, Conan Doyle, and Buchan’, in B. Bond, B ed., The First World War and British Military History. (Reprinted hardback edition, Clarendon Press Oxford: 2002)

Keegan, J (1978) ‘Whole Stunt Napoo’, New Statesman 17 November 1978

Hammond, M and Williams, M. (2011) British Silent Cinema and the Great War (Palgrave Macmillan 2011)

Hanna, E. (2009) The Great War on the Small Screen: Representing the First World War in Contemporary Britain (Edinburgh University Press, 2009) p. 52

McLuhan, M (1062) The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man; (University of Toronto Press 1962)

Moran, J. (2013) ‘Armchair Nation: an intimate history of Britain in front of the TV. (Profile Books, 2013)

Strachan, H. (1991) ‘‘The Real War’: Liddell Hart, Cruttwell, and Falls’ in B, Bond, ed., The First World War and British Military History. (Clarendon Press Oxford. 1991)

Sir Douglas Haig by J P Harris (2008)

Created in SimpleMinds. get in touch if you’d like a copy. Download the SimpleMinds App for free.

Douglas Haig and the First World War (2008) J P Harriss

Nearly 600 pages that follow a chronology that is familiar. Insights on Haig are limited – perhaps reading Haig’s diary and a biography at the same time would help. This is written by a military historian with judgement of Haig’s command key. We get little insight into the man – if there is much a a personal life to probe. His diary appears to reveal little. What does come over is how often Haig was to blame for actions that were unlikely to succeed in doing much other than expending a good deal of munitions and men – time and time again he planned an offensive that would lead to a break-through, require cavalry support and put tens of thousands of men against barbed wire, machine guns and shrapnel. His greatest skill was to climb and keep climbing the ladder of promotion and to tread carefully around events which might have led to his being passed over for promotion … or his resignation asked for, or accepted.

My first read. A second read possibly to follow unless I can be pointed to a biography.

Notes as iPhone/iPad pictures with annotations (Studio) and a mindmap (SimpleMinds)

Britain had been preparing for war with Germany as is clear from manoeuvres, in this instance with both France and Russia, in 1912 (Harris, 2008:51). Perhaps the re-organisation of the Army to have the Expeditionary Force, however small, was part of an anxiety and vulnerability – had Britain not also contemplated conscription?

As the nature of artillery changed – longer range, great accuracy and a diversity of shells types from high explosives to shrapnel it is staggering that proper thought wasn’t given to how destroyed the land was over which the armies would have to travel.

Typo alert! Actually there are a couple more but I so no value

Where tactics have failed to deliver why did Haig persist? How could more of the same possibly get better results next time? What part of his mindset made him stick to this? Does he lack imagination? He appears emotionally dry or aloof – his relationship with his wife and family hardly suggests a person with a close emotional attachment.

Haig’s greatest skill and purpose was to climb to the top of the Army ladder – what he did or could do when he rose to the top was another matter. This isn’t what makes a great leader – he is like a career civil servant. But what would a hot headed, womanizing, gambler of a man done with this power? If Haig made mistakes they need to be considered and compared with other leaders on the Western and Eastern Fronts. Had Britain a leader like Foch, Neville, Falkenhayn or Holweg … or the Russian aristocrats would we have fared better or differently? And if we’d had Robertson rather than Haig?

History written by a military historian is different to history or biography – the audience here is expected to learn and potentially apply at staff level the lessons from past battles. Haig’s diary is revealing because in this supposedly private moments he is reveals so little: statements of the weather, not what this could mean, statement of events without reflection on what he did well or badly. Self-control in both his public and private life.

To understand Haig then we need to know who the alternatives might have been and whether in reality they could or would have behaved differently: Robertson, Du Can and Rawlinson are different men.

My impression is of a deluded fantasist with no one able or willing to stand up to him … not even Lloyd George. Haig, with Royal patronage and few competing for his role, could and would do as he pleased. He resented having to play second fiddle to the French. In the early stages of the war he ignored orders or requests with potentially dire consequences yet he got away with it.

Haig’s tactics: more munitions, human dynamism and officers of the ‘thruster’ type – people who would risk all regardless. Is there anything we can learn from Haig’s achievements as a polo player from this? What does it require to win at polo?

Haig pressed on with tactics that would leave many thousands dead for little gain and he wasn’t able or willing to question what he could or should do differently.

How clear did failure have to be to get Haig to change his tactics?

Failure of this kind should surely have seen Haig replaced? To what extend did his ‘moral fibre’, his otherwise untarnished character, make it less easy to remove him?

Overexcited, overoptomistic, blind to failure, forever looking beyond the horizon, convinced cavalry had a role, yet able to try gas and tanks … anxious for his peers and superiors to shower him in praise and his subordinates to be fawning …

Self-righteous and self-assured – did his religious beliefs permit his unstinting view of the world? He had the image of someone who deserved authority and respected it. He was fit, sober and in a stable marriage. He worked hard and played the game well. Born into a different age could he have survived? He lacks the flair of Montgomery or Churchill. Described as taciturn, to what degree might or could his asthma have been a controlling influence?

He looked the part and was fastidious about his health – what else could as asthmatic do in the early 20th century? Did he know what the triggers were, or had he learnt from experience to avoid certain foods and situations – not least smoking? Was he prone to chest infections?

Whilst those around him realised all talk of a ‘break-through’ was unrealistic, this is what Haig constantly planned for and expected. Or was it simply wishful thinking?

Step by step is what occurred … as a result from efforts to breakthrough? A case of shoot for the stars and hitting the moon? That in Haig’s eyes step by step would have equated to inconsequential nibbling?

Obsessive, selective, fixated, God-guided, controlling, cavalry-orientated, driven obdurate, blind … consistent, controlled, tempered, magisterial … aloof and with tunnel-vision.

Able to comprehend, but unable to bend? Unable to think of any alternative. The world around him changed, but Haig stayed resolutely in the 19th century.

Chance the way the leaders played off against each other? Men like so many bullets or sandbags, simply a resource to count then stack in the knowledge that there would be great losses but that these could be shored up?

He didn’t like to have his feather’s ruffled. He wanted the game played in his way with him in charge.

A hypocrite who would fail to come to the aid of others … yet others to come to the aid of him. Too good or important to warrant risking his men, or putting his men under another’s control and willing only at the last minute to seek help when things looked desperate and he had no choice.

Related articles

- Haig was no hero (machineguncorps.com)

- Museums watch: The poppy and Reading (getreading.co.uk)

- ‘Your Country Needs You’ (thesocialistway.blogspot.com)

- Alex Massie: War that changed a nation (scotsman.com)

- The First World War Pt.5 (detectingblackpool.wordpress.com)

- Canada and the First World War (anoctoberhorse.wordpress.

The dead then are the cartridge empties of today

Fig. 1 Death in Passchendaele exactly as my grandfather described it

Had the public seen, and seen repeatedly, what death looked like between 1914 and 1918 perhaps the public outcry would have brought it to an early end. Or not.

The dead then are the cartridge empties of today.

Beyond comprehending the opportunities of open learning and the theory behind the processes that occur we as ‘educators’ still need to deliver content, to create an event, put on a show, get attention, set the tone for a programme of work. Martin Weller thinks that being media savvy is to add some downloaded graphics or snapshots to a slide, actually, the art and skill of communication as anyone in advertising will tell you is far more able to leave an impression. Making a bar of soap interesting is a challenge, making war interesting should be easy so long as you stick to what attracts interest: fighting and death. Three decades listening to my grandfather and I can only now take on board what it must have been like to be stuck, repeatedly, in a confined space, in harms way, with a buddy or two at your side, horribly wounded and slowly dying.

Fig. 2. Marking the spot where my grandfather buried Dick Piper and Henry Gartenfeld

75 years after these events my grandfather returned to the very spot where this occurred and he broke down to think how they died, and why they died and the lives they never had but deserved, let along the wife and kids one left behind. He never recovered from that trip and died himself a few months later – it was as if death had touched him to the soul and after 97 years he could put it off no longer.

The Pity of War: Mindmap for a Book Review

Fig.1 SimpleMind Mindmap based on Niall Ferguson’s ‘The Pity of War’

I’ve now read ‘The Pity of War’ twice in a row. As I’ve gone through it I’ve highlighted passages and added notes

and tabs in Kindle. I also grabbed a few highlighted passages and put them into the iPad App ‘Studio’ to annotate and took slides from a

presentation on how to prepare a book review by Dr Pete Gray of the University of Birmingham and annotated these too.

On the second reading I created the SimpleMinds mindmap above.

This ought to be my starting point for a solid 1,000 word book review.

Further reading in the from of Books and papers of interest have been picked up along the way too.

Those to find in a university library, those acquired secondhand through Amazon or uploaded as eBooks in Kindle and papers I can find as a postgraduate student online, either through the Open University or the University of Birmingham (I am a postgraduate student at both). There are various ways I can offer the above, though the best is to download the FREE version of SimpleMinds and read it that way.

Offered with a view to sharing the views of others.

I can export it into a word file and develop the categories I already have as separate themes:

Insightful (in yellow) has some 52 notes, most referenced by Kindle Link (KL).

Do I buy the print version or go to the library and cross-reference?

Descriptors: meticulous, original, weighty, highly referenced, all sides, high brow, thoroughly researched, well read … often

intricate, taking us to detail researched by others? NOT, as he says in the introduction, a textbook or a narrative of the war.

No Trivia – nor the chronology if the war, nor countless aggregated memories of veterans, though there is a bit of poetry and some

mention of movies and TV films from ‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ to ‘Birdsong’, ‘Gallipoli’, ‘Blackadder goes forth’ and

‘Ghost Road’ Bias – I wonder about this in relation to where Niall Ferguson – that he relishes a dig on the landed gentry and public

school system, their types, behaviours and hobbies, from leadership to country sports.

Debunking myths: the desire for war, the Germans to blame, the Russians to blame, militarism, German economic efficiency, not donkeys, the AEF didn’t win the war and blundered in making the mistakes of 1914, naval supremacy and ambivalence to war.

The Press – censorship, Buchanan, DORA. Finance – givernments

and bankers.

A dilletante, too thorough, comprehensive: penny dreadfuls, invasion stories, art history and drama, from Karl Kraus to Oh What a Lovely War.

Errors or mistaken emphasis: Fashoda, conjecture that Grey et al. exaggerated the threat of Germany despite intelligence, attempting to interpret stats on fatalities, wounded and prisoners, the Entente were better at killing, maiming and taking prisoners, Tommy gets angry with a Jerry prisoner, All

Quiet on the Western Front is not biography though Ferguson quotes from it as if it is. Remarque wasn’t a front line soldier. The Oxford Union as any kind of representative body for comment. That Belgium neutrality would have been breached by GB. That skilled workers lost to the war impacted our economy when women very effectively stepped in. That the EU in its current form might have emerged has GB stayed out of it. That waving Tommies are from a photo archive when they are grabs from the Battle of Somme footage.

Kinds of historian: cultural, military, diplomatic, economic.

Why was recruitment successful? Recruitment campaign, female pressure, peer and employer pressure, impulse, economic motives, and more?

Other historians and commentators:

Alan Clarke, Lidell Hart, John Terraine, Correlli Barret, Michael Howard, Norman Stone, Lafell, Bidwell, Graham, Travers, Holmes, Martin van Creveld, Dominic Graham, JMBourne, Michael Geyer, Martin Samuels, Gudmannskn, Paddy Griffith, Theo Balderston, Knaus and Hew Strachan.

With distinct sections on:

Finance and JMKeynes Writers

With a bit on poets, and rather less on films and art.

What did he leave out then?

- Women

- The Home Front

- Technological developments, especially in the air

Fig.2. A brief response to the ten questions Ferguson poses at the start of the book and attempts to answer by the end – I’m not wholly convinced.

WWI MOOC

Fig.1 Underdtanding the Great War

As an MA student on the Bham First World War studies programme we are reading and then writing a book review on Niall Ferguson’s ‘The Pity of War’. The consequence for me is a significant growth in my library of First World War books, and eBooks such as this one. Meanwhile, with this contrasting worlds of real and virtual playing out in parallel workds I am doing the Open University MA in Open and Distance Education module H818: The Networked Practitioner. I’ve done three MOOCs. Is this how a campus based taught course at Bham lauches itself into 21st century education?

PR RELEASE

Posted on Wednesday 16th October 2013

The University of Birmingham is linking up with the BBC to create an academic first – a unique distance learning course marking the centenary of the First World War next year.

The ‘Wings of Modernity’ course, developed by the University’s Centre for War Studies in conjunction with the BBC, was announced during a press conference outlining the BBC’s forthcoming World War One Centenary coverage today (Wednesday 16 October). It will be a pilot Massive Online Open Course (MOOC) looking at the evolution of airborne conflict, published on the FutureLearn platform.

Controller of Learning Saul Nassé says: ‘The BBC continues to be excited about the development of MOOCs – Massive Open Online Courses that will enable mass participation in learning online. We are keen to explore opportunities with a number of University partners as part of our WW1 coverage. The first one to be developed will be with the University of Birmingham, the short course will cover the deployment of air power during the First World War and attitudes to the use of new technology.’

Dr Jonathan Boff, lecturer in war studies at Birmingham, commented: ‘This exciting initiative will give us a chance to share our passion for First World War history with the widest possible audience. It also enables us to continue our pioneering use of digital technology both to support existing students and to attract new ones. Students stimulated by the MOOC can easily pursue their interest by exploring our wide range of full-time and part-time undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, online and face-to-face, in war studies and the history of warfare.’

Director of the Centre for War Studies Dr Peter Gray added: ‘The University of Birmingham has, in the Centre for War Studies, the largest and longest-established centre for specialist research and teaching of the First World War anywhere in the world. It is also internationally renowned for excellence in the study of Air Power.

‘The ‘Wings of Modernity’ MOOC will bring together our strengths in both areas to allow students to explore, not only the Great War in the air, but also the impact the war had on aviation more generally, and more broadly still to examine developing attitudes to technology in a time of revolutionary change. Although we often take aeroplanes for granted today, the story of how we got to this point is a fascinating one whose roots lie in 1914-18.’

In a separate but related development, the Centre for War Studies is one of the Universities providing academic advice and support to the BBC’s digital content for the First World War centenary.

This will cover a range of material designed for audiences from as young as five years up to those as old as the war itself and is evidence of the commitment of both organisations to explaining the history of the Great War to the widest possible audience.

Notes to editors

Dr Jonathan Boff is Lecturer in War Studies at the University of Birmingham, where he leads the MA in British First World War Studies and an online-only MA in Military History by Distance Learning.

Dr Peter Gray is the Royal Aeronautical Society Senior Research fellow in Air Power Studies at the University of Birmingham and Director of the Centre for War Studies. He has published widely on a range of air power subjects from historical issues through to contributing to current debates on remote warfare such as the employment of drones. He has extensive practical experience from his time in the Royal Air Force and is in demand worldwide for his knowledge of air power history, theory and practice.

The Centre for War Studies at the University of Birmingham is one of the leading institutions of its kind in the United Kingdom. It brings together academics from around the globe to research and teach military history. With particular strengths in the study of the two world wars and the history and theory of air power, it offers a wide range of undergraduate and postgraduate courses and maintains a unique network of alumni and associates active in the field of military history and war studies.

For media enquiries please contact Jenni Ameghino, University of Birmingham Press Office, +44(0)121 415 8134 / +44 (0)7768924156